Press Pause: Distracted Spectatorship in the Streaming Era

Leona Heimfeld

Email: lh715@exeter.ac.uk

Download the PDF of this article

ISSN 2752-3861

Abstract

For this article, I want to present a snapshot of contemporary streaming and consider how distracted viewing has become normalised for some young women since the pandemic. While distraction was noted from early studies of cinema and television spectatorship, I will link contemporary viewing to Netflix’s encouragement of interaction through frictionless controls. Seeking to contextualise viewing on streaming sites within wider developments in spectatorship, I consider how the pandemic has accelerated distraction by blurring boundaries between work, school and home. Finally, I explore commercial opportunities for interrupted spectatorship on streaming sites.

Introduction

In 1994, Roger Silverstone pointed out the all-pervasive nature of television, and how watching does not easily separate from the ordinary life of the viewer (Silverstone, 1994, p. 24). What would he make of the daily spectatorship of a teenager in 2022? For the past ten years, I have taught Film at an all-girls independent high school. My students don headphones to stream shows on their phones when travelling for up to one and a half hours on the morning bus journey. They arrive to their form rooms where they sit silently texting and watching clips from TikTok or YouTube. Blended Learning lessons are interrupted by dying laptops. Then at the end of the day, streaming on the long journey back home. This doesn’t even take into consideration the upwards of three hours a day spent watching for leisure after school. Ofcom’s research for 2021 showed that 16–24-year-olds watched an average of five hours and 16 minutes per person per day with SVoD (subscription video on demand) the largest type of content at an average of 85 minutes, overtaking YouTube and broadcast TV for the first time (Ofcom, 2021, p. 22). Since the pandemic, my students have normalised rapid shifts between different modes of watching – for learning and leisure, in groups and solo, focused and multi-tasking, mobile and stationary. Viewer control over time, place and mode of watching has been examined since the introduction of remote-control devices, VCRs and DVD box sets. As developments in technology require programmers to find new ways to harness distracted spectatorship, John Caldwell (2003) points out how new media platforms are most successful when they utilise more subtle methods of keeping hold of migrating viewers. I want to explore how distraction is encouraged by the Netflix Pause button, combining consumer choice with unseen information gathering.

William Uricchio called television “a medium in near-constant transition” (2009, p. 72), and the terminology I use incorporates how contemporary streaming merges aspects of the cinematic ‘spectator’, the televisual ‘viewer’, and the internet ‘user’. Recent studies have identified spectators of algorithm-enhanced culture as “co-producers” of content (Martinez and Kaun, 2021, p. 198), a definition I am keen to interrogate. Differentiating my terms for disengagement from streaming spectatorship, I refer to ‘distraction’ when a viewer is drawn away from the programme, possibly temporarily, but possibly in a more persistent way. In this case, the viewer is mainly focused on the programme. When viewing is paused or halted, and the focus is mainly on the cause, I define it as ‘interruption’. Finally, I use ‘disruption’ when there is a simultaneous and ongoing distraction, and the viewer is trying to watch the programme but is unavoidably unable to fully focus. I have titled my article ‘distracted spectatorship’ because my observations suggest that viewing is persistent, even when halted, forming a continuous backdrop to daily life.

My PhD is called Contemporary modes of spectatorship: Netflix, young female viewers and the impact of the lockdown experience. I question whether spectatorship on streaming sites is forming interactive negotiation with gender expectations in films and series. Mia Lovheim has argued how young women’s blogs are performative spaces, giving them the chance to “negotiate social norms and cultural values; voice issues of common concern; and contribute to forming public opinion” (2011, p. 350). I see the choices that young women make in viewing as an extension of their online social life. Therefore, my research explores watching on streaming sites as finding internal, personal and solo motivation, but expressed through shared and collective performances made by participants. My starting points are observational: through questionnaires, discussion groups with my students and my own teaching experiences, I consider areas for further academic research and studies of empirical data, which I use to triangulate my findings. Drawing upon feminist media studies, I investigate how Netflix impacts the spectatorship of some young women, due to the appeal of its platform, content and its ability to disrupt normal modes of viewing. Alongside engagement with programmes, such as binge-watching, I am also interested in spectatorship which disengages – distraction and deliberate rejection of what is being watched. Two areas I examine are hate-watching and passive activism, whereby switching off misogyny, racism and homophobia might demonstrate how contemporary intersectionality works in practice.

Press Pause

It is seemingly innocuous; I am binge-watching Bridgerton and press Pause. This may be temporary – to eat, to answer the door – in which case I will return imminently to Anthony’s wet frilly-shirt moment. Or I may pause mid-episode of Parks & Rec because I need to sleep, knowing that Netflix will remember where I was when I next click on the icon. The Netflix Pause button embodies these contradictions of choice, placing power into the hands of the viewer and acting as a trigger to provide the streaming company with data.

Controls provide audiences with what Henry Jenkins in Convergence Culture called “the right to participate” (2008, p. 24) in the culture they consume, but these interruptions in viewing enable Netflix to have a constant feed of habits, likes and dislikes. Mattias Frey describes Netflix and its algorithmic engine as a personalisation service – “a matchmaker between media content and users” (2021, p. 46). The recommender system compiles data on what is watched as well as how – a device used, time of day, day of the week, the intensity of watching – and what was not watched, including suggestions hovered over but not played (Gomez-Uribe and Hunt, 2015). The success of the Netflix algorithm is in its invisibility; it helps users find satisfying content, which is instantly consumable on the platform. As algorithmic systems exist to “focalize attention and reduce the unmanageability of cultural choice” (Frey, 2021, p. 42), making attractive recommendations relies on browsing and pausing to allow compiling of data before and in between viewing.

The disruptive functionality of the Netflix Pause has an antecedent in historical television controls. Uricchio points to the “subversive” nature of the remote-control device from the 1950s, signalling a change to scheduled programming and advertisements by offering “a set of choices and actions initiated by the viewer” (2004, pp. 170-171) including strategic interruption of broadcasts by rapid switching of channels and muting. Anne Friedberg goes further, suggesting that giving the television viewer power through “interactive usage instead of passive spectatorship” (2000, p. 442), aligns the experience with consumerism (1993, pp. 141-143). Recordings of previously broadcast programmes enabled television spectators to own what had been ephemeral, elevating fans to discerning collectors.

Derek Kompare highlights how the introduction of the VCR was a “reconception” of television (2005, p. 199), by which the purchasing of programmes altered the spectator’s relationship with the media text. Video on demand and cable companies such as HBO aimed to differentiate their products from broadcast television by marketing their quality and exclusivity. In fact, Netflix’s original promotions positioned streaming as more refined for the viewer (Tryon, 2015, p. 106) while subscribers were admired for pro-active viewing, “hunting online for shows, planning ahead and downloading overnight” (Strangelove, 2015, p. 103). Users were offered seemingly endless control over watching, with the caveat that they should subject their behaviour and actions to tracking. As Daniel Chamberlain notes, the shift from simultaneous spectatorship on broadcast television to asynchronous viewing on streaming sites offers flexibility and portability that is “both empowering and surveillant” (2011, pp. 20-21).

How does the streaming site know that 20 minutes into Episode One I paused because Emily described Paris as “just like Ratatouille”? Netflix’s viewing data architecture creates an event at the start of the film or series, and the system logs how much is watched, allowing users to seamlessly pick up from where they paused.

According to the Netflix Technology Blog (Fisher-Ogden et al., 2015), there are three key questions that drive data mining:

- What titles have I watched?

- Where did I leave off in a given title?

- What else is being watched on my account right now?

Questions 1 and 3 collate data of choice and point you to recommendations.

Question 2 allows Netflix to remember where you were in the show so that you can resume viewing.

If I pause after 20 minutes of The Kissing Booth 2, Netflix knows that something happened to make me stop watching. Either viewing was interrupted to do an activity, or the film made me lose interest at that point. If I regularly pause at 11 pm then Netflix infer that is probably my bedtime. If a large number of people fast forward 10 minutes into the second episode of series three of Riverdale, then Netflix garner that the audience got bored, when yet another serial killer plot was introduced. If I just watched every film or episode on Netflix right the way through without pausing, the only data gathered would be the single choice of film or series. Every time I pause, more information is created, so more interaction equals more data.

Personalised recommendations

Pierre Bourdieu wrote that consumers “distinguish themselves by the distinctions they make” (2010, p. xxix), and, on Netflix’s machine learning-based algorithm, viewers’ active discrimination creates a constantly changing real-time patchwork of preferences. As I open the site, the Recommendations grid on Netflix is designed like a bookshelf and the system notes what attracts my eye and for how long, as my mouse hovers over the titles. Like my hand picking up a DVD to read the blurb, clicking on the image triggers further data collection. Do I choose to play, or do I reject?

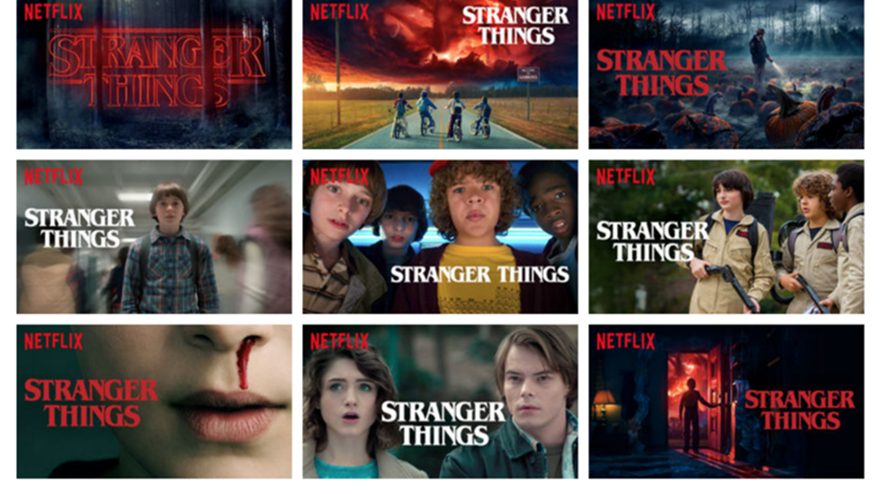

The former Head of Machine Learning at Netflix, Tony Jebara, admitted that everything on a user’s Netflix landing page, including the programme images and trailers, is “personalised” (Jebara, 2019). At a New York University talk in 2019, Jebara showed that there are at least nine different thumbnails for Stranger Things (Fig. 1) that could appear on the shelf depending on whether I have recently watched horror (in which case I would be shown the image of Seven’s nose bleeding on the bottom left), adventure (the Spielbergian line up of boys in the central image) or romance stories (in which case I will get Jonathan and Nancy).

Genres are not the only way that Netflix build recommendations, they also qualify programmes according to mood, aesthetic, and pace. Subsequently, shows are grouped according to categories created by the company – anti-heroes and moral ambiguity, sharp humour and strong female leads, dangerous worlds and complex consequences. There are over 3,500 base categories from ‘Action and Adventure based on a book from the 1960s’ to ‘Witty War Movies’ (What’s on Netflix, 2021). Whenever you hover over or click on a thumbnail, you are triggering interest in a range of categories. Boasting that they offer over 250 million tailored experiences, Todd Yellin, Vice President of Product, said, “We factor diversity into the algorithm to prevent an echo chamber” (Chhabra, 2017) – meaning that just because you have watched ‘horror’, the system recognises that doesn’t mean you only want to watch ‘horror’.

Originally, Netflix employed a five-star rating system for customers to leave feedback on films and shows that they had watched. But this was removed in 2017 because the star ratings were thought to be aspirational, and as Yellin told The Verge “What you do versus what you say you like are different things” (Goode, 2017). Furthermore, the value of the star rating system was misunderstood by viewers who assumed it was an average mark based on all feedback. Instead, each subscriber received a personalised rating based on previous viewing habits and an overall average score (McAlone, 2017). A predictive percent match score was used while Netflix developed a global database of activity, monitoring real-time customer behaviour – what did you stop watching, when did you stop watching, did you ever go back? The evolution of the platform went from a viewer rating system to machine learning that adapts to the interests of the subscriber. As Frey notes (2021), this effectively shifted the recommendation focus from similarities between users’ tastes to similarities between productions mined, thereby removing aspirational choices, virtue signalling and gender expectations.

A complex and multi-layered picture of each viewer is created by data mining. As Chief Content Officer Ted Sarandos said, “It’s just as likely that a 75-year-old man in Denmark likes Riverdale as my teenage kids” (Adalian, 2018). In fact, Netflix is moving away from categorising spectators as the traditional dialectically opposed groups – young vs old, women vs men. Acknowledging that the controls view the login as a composite person, Jebara noted, “we still just act like it’s all one user…because we’re all kind of a mixture of different contexts and moods” (Jebara, 2019). When building data analysis of their subscribers, it doesn’t even matter that multiple users may be watching on the same account. In this way, Netflix directs spectators towards wider viewing, curating a range of recommended programmes and films that may take the viewer out of their comfort zone, while acknowledging qualities that they have previously liked. What this means in practice is that a little-known film such as Alice Wu’s low-budget progressive romance The Half of It will get recommended to a wider range of subscribers than the blockbuster Jurassic World because it is identified in 10 distinct genres. On the positive side, this allows independent films and diverse series to find an audience in ways that would not have been possible in a marketing-based platform.

Time: Flow diverted

In the mid-1970s, Raymond Williams described watching a film on American television, seamlessly interrupted by advertisements and trailers for further programmes, so that he felt the actors and plot of the commercials and films merged into “a single irresponsible flow of images and feelings” (2003, p. 92). Perhaps the most visible structural characteristic of broadcast television is how the schedule aims to smooth interrupted viewing, both between programmes shown and within shows through advertising or trailers. Jarring when a show is finished needs to be reduced or the viewer will change channels, so schedulers smooth the cracks with trailers for upcoming shows and station identifiers to create Williams’ unifying “flow”, with the experience of watching television likened to being carried from one programme to the next. Until the early 1980s a handful of television channels broadcast for just a part of the day, what John Ellis calls the medium’s “era of scarcity” (2000, p. 39). Production schedules drove the output – soap operas during the daytime for housewives, children’s programming in the afternoons, news after dinner in the evening, more adult themes and violence after the watershed – targeting specific audiences at specific times.

The introduction in the early 1980s of home video recording on a VCR allowed ‘time shifting’ of programmes, enabling viewers to watch at their convenience. For most early VCR users, the content captured was temporary, easily recorded over to make way for the next show, but an increasing number of fans began to create libraries of their favourites. David Gauntlett and Annette Hill note the similarity of home video recording to manipulating information on a computer – “the basic ‘cut and paste’ function” (1999, p. 148) – building on the growing availability of home computer technology. These changes in consumption of television content redefined spectators, audience and viewers into users, consumers and collectors (Kompare, 2005), and by the mid-1990s it was more common for pre-recorded videotapes to be purchased rather than recorded or rented (Gauntlett and Hill, 1999), paving the way for bypassing of the broadcast schedule.

Jana Zündel (2019) and Marieke Jenner (2021) highlight how network channels offering marathon weekends to promote upcoming seasons and HBO marketing its high-quality long-form series as buyable DVD box sets set the precedent for extended watching of long-form series. From the launch of Netflix Video on Demand in 2007, subscribers were able to access entire seasons of serial content from the moment of its initial release, promoting binge-watching as the expected method of consumption. As Jonathan Friedland, Head of Communications at Netflix, said, “We put the consumers in charge of their own experience” (Baldwin, 2012). Recent studies have focused on how Netflix is designed to keep users transfixed: Anne Sweet likens binge-watching to an “addiction” (2018, p. 167), citing the difficulty of disengaging from the screen, while Jenner (2018) highlights how the onus is placed on the spectator to opt-out of continuous viewing. Yet, disruptive interaction is needed to maintain the illusion of continuous programme content, and the Netflix controls of Automatic Play and the 5 Second Countdown Clock aim to disguise interruptions between episodes. Netflix recently claimed that on an average day Skip Intros is pressed 136 million times (Johnson, 2022).

In an age when the viewing audience is further fragmented, interruption encourages simultaneous use of social media. Ellis highlights how broadcast television “connects with the private and the disconnected moments of individuals, with diffuse feelings of escape and distraction” from modern life (2000, p. 176). As a subscription-only platform, it is vital for Netflix to build publicity for its shows, whether or not they get an audience. Multi-tasking is actively encouraged by the streaming site, offering Easter Eggs hidden within programmes and pushing the social media profiles of stars such as Noah Centineo, Lana Condor and Lily Collins (Fig. 2), the last of whom has over 23 million followers on Instagram. My students speak of the sheer enjoyment of being able to text with friends while streaming. As Yvonne Tasker and Diane Negra note, post-feminist culture seeks to “commodify feminism via the figure of a woman as empowered consumer” (2007, p. 2). According to feedback from my students, so much of the content young women watch is actor-driven and they note that fandom is made easier by Netflix controls such as 10 Seconds Back, which smooths over a short disruption by allowing immediate re-viewing. Furthermore, they can repeatedly replay a relished favourite moment, examining it in forensic detail.

Multi-tasking while watching blurs the line between focused spectatorship and living everyday life. One student confessed that Big Bang Theory and Grey’s Anatomy feature in regular 5-hour viewing sessions while simultaneously playing Minecraft. Steadily increasing hours of binge-watching suggest that the streaming spectator’s concept of time is complicated: to maintain a satisfying quality of viewing over an increased quantity of time requires interruptions that constantly disrupt and yet maintain the pleasurable flow. As Ethan Tussey notes, while the business model of synchronous viewing has been disrupted by time-shifting technology, second-screen apps on a range of devices including tablets, laptops and phones replicate a sense of community through gaming and social networking (2014, p. 206). Commenting on social media while watching adds another layer of turning the private spectator into a public commodity, promoting further consumption of an already consumed programme.

The impact of the television remote was to effectively turn the viewer into a montage editor, able to surf between channels with a zap of the fingertip (Friedberg, 2000). Similarly, Netflix controls enable the viewer to curate an infinite number of unique adaptations of a fixed programme or film. One of my students admitted to skipping over all of the non-Kate Winslet sections of The Holiday, finding the Cameron Diaz/Jude Law romance boring. Compulsive skipping ahead is described by another student as her normal way of watching. The moment a show gets to a point she finds dull or has seen before and knows it isn’t interesting, she fast-forwards. Others have articulated that the moment there is a scene of sexual content that they find embarrassing, they skip over it. Thus, Netflix controls allow the viewer to interrupt the narrative arc, shifting the climactic structure. While Jason Mittell points out that bingeing a DVD box set creates a “mad rush for narrative payoff” (2015, p. 39), my students suggest that extended and repetitive viewing on Netflix is geared around avoiding boredom. Compulsive fast-forwarding aims to avoid time waste, so that the film ceases to be a cohesive story and is exposed as a string of disjointed moments. Once the editing glue that holds the narrative together has been unsealed, the spectator creates a remodelled version of the film or series. This could be a re-imagined version of the plot but is more likely to produce a sequence of favoured moments that form an ideal version of the characters.

Place: Blurring the boundaries between work, school and home

While Christian Metz (1976), talks of the spectator’s body immobilised when watching in the cinema, fixed to the spot, Ellis (1994, p. 137) suggests that the domestic setting and round-the-clock availability of programmes moves watching into the background and “no extraordinary effort is being invested in the activity” of the televisual glance. Domestic distraction formed the basis of gendered television research. From interviews conducted in the 1980s, David Morley noted that the home was viewed as a place of women’s work, so that while men watched television with a focused gaze, women could only do so “distractedly and guiltily” (1986, p. 147) due to their domestic responsibilities. This power imbalance is further picked up by Charlotte Brunsdon in Women Watching Television (1986, p. 106): that while the male watches with a fixed, controlling and uninterruptible gaze, the domestic female gaze needs only “an intermittent glance”. Women watching television without multi-tasking were seen as indulgent and lazy. Furthermore, Morley (1986) and Kuhn (1984) note how the schedule placed gender-targeted programmes into the routines for housewives and their husbands at different times of the day, with soap operas coinciding with the daytime routines and domestic activities of housewives and mothers.

Sean Cubitt (1988, p. 76) refers to television viewing as ephemeral in its broadcast form and that the images seen are only “intermittently present”, perpetually on the edge of disappearing. The relatively small size of the television image in comparison to the cinema screen, the fact that it is often viewed in light rather than darkness and the lack of visual definition on the domestic television set all pointed to what was presented as an inferior experience of spectatorship. Unlike the collective audience experience in the cinema, the family unit watching the television set in the living room has been aligned with a retreat to individualism and rejection of the community. However, Lynn Spigel in her examination of early American television and the suburban home, Installing the Television Set suggests the distinction between public and private spheres in 1950s suburbia was not so straightforward. Spigel (1988) argues that the layout and architecture of tract housing formed both a connection and disconnection between neighbours; separated into identical detached houses yet linked by newly laid communication wires and roads. Behind the curtains and picket fences, watching television enabled spectators to be physically alone and consciously united at the same time.

While Morley (2004) notes that the living room television set was often hidden within the décor as it was seen as disruptive of domestic life, multiple devices throughout the home have enabled simultaneous, yet individual, viewing. The mobility of tablets, laptops and smartphones became vital when the UK’s first Covid-19 lockdown began on March 23, 2020. With millions of adults and students isolating at home, domestic and work boundaries were blurred. Soon after, Netflix released a sober announcement noting the enhanced role that the company would be able to play during the worldwide crisis: “At Netflix, we’re acutely aware that we are fortunate to have a service that is even more meaningful to people confined at home, and which we can operate remotely with minimal disruption in the short to medium term” (Rushe and Lee, 2020). Netflix offered its platform as a relief from chaos and confusion. Recent scholarship by Neta Alexander (2021) and Tanya Horeck (2021) noted a pandemic re-evaluation in which binge-watching was no longer viewed as an unhealthy indulgence, but rather an emotional and communal coping strategy. Previously mocked as ‘couch potatoes’, viewers who repeatedly watched favourite episodes of long-form series during lockdowns were praised for finding a successful means to de-stress.

Confined to the home, but attending school online, my students had to present their public persona while still in their personal space. This gave me an insight into contemporary online viewing, because although in a lesson, the students demonstrated their ‘at home’ behaviour. Jo Littler points out how the language of equality and identity politics merge as entrepreneurial behaviour extends into the “nooks and crannies of everyday life” (2018, p. 2); my view of students during lockdown revealed atomised individuals. Private space was limited, so they were often attending in their bedroom. At various times parents, siblings and pets interrupted their lessons, as different schedules clashed in the household. Suddenly moving around the house to get a snack or grab some paper caused dizzying effects, revealing how their viewing is no longer static. At home, students are used to pausing viewing and interacting with others online or in person. I was surprised at how comfortable the students were with being watched and witnessed how rarely students were actually looking at the screen. As Joshua Meyrowitz notes, “the public is familiar and comfortable with surveillance activity after participating in a form of it themselves” (2009, p. 47). Young people are constantly seeing normal people’s activities online in reality shows, TikTok and YouTube videos, so there is an expectation that surveillance is normal.

Conclusion: Commercial opportunities in the future of distracted viewing

Benjamin Bratton refers to how the global interconnection of digital, virtual, and physical technologies creates an “accidental megastructure” called “the stack” (2015). This architecture is invidious because it does not surround us the way that buildings or cities do; rather it is a construct of our discrete individuality created through interacting with online algorithms. Spigel outlined a connected individuality for television spectators in the suburbs, but Bratton is describing a global interaction that is unique for each spectator. What we see and how we see it are increasingly experienced in our own individual stacks. In many ways, the criticism of distracted television viewing has been brought full circle, suggesting that rather than indicating failure to show distinction, distracted streaming is a form of fluid negotiation. Interactive spectatorship demonstrates what Catherine Driscoll calls “a mobility of interest” (2002, p. 224), suggesting dynamic viewing with a multiplicity of responses.

Netflix initially mined the data to inform user recommendations, but more recently the algorithms have become useful to point audiences towards their extended original content. As Blake Hallinan and Ted Striphas (2016, p. 128) point out, while audience data was previously used to find the lowest common denominator as a focus for advertising, Netflix data collection is for the purposes of creating “highly differentiated micro-audiences”. In 2021, Netflix.shop was launched in the US, offering merchandise (t-shirts, toys and jewellery) linked to programmes. However, the press release hinted that the future of clicking Pause may also involve immersive events and games, noting “we love it when great stories transcend screens and become part of people’s lives” (Simon, 2021). This was followed by FYSEE 360, a platform for fans to explore scenarios for Stranger Things, The Crown, Queer Eye and Tiger King (Brockway, 2020). Jenkins warns that to gain loyalty, content producers need to provide spaces for fans to make creative and interactive contributions to programmes (2008, p. 173), and in May 2021, it was suggested that the N-Plus platform may offer viewers the chance to influence the development of series in pre-production (Carson and Roettgers, 2021). Interactive programmes have featured on Netflix before, with viewers choosing from a range of pre-filmed options for Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt and Black Mirror, but these recent immersions go beyond the physical watching of the programme. By conflating the roles of user and observer, what M.J. Robinson calls “the viewser” (2017, p. 3), these innovations suggest that Netflix is looking to layer the experience of watching, rather than divert attention towards or away from programmes.

The key to further diversion appears to be the diversity of original content on the site. In March 2022, Netflix purchased Night School Studio and Next Games, having announced to its shareholders that gaming would provide another new content category (Netflix Q2, 2021). In considering a future Netflix multiverse, it is interesting to look at how Epic Games, who own Fortnite, recently produced a digital Rift Tour with an avatar Ariana Grande where players were offered the opportunity to purchase virtual reality concert outfits and interact with the popstar (Fig. 3).

As one reviewer remarked about the experience, “Instead of just watching a performance in a video game space, we were going on an epic journey with Ariana Grande guiding us through like Charon with butterfly wings” (Zucosky, 2021). Linking machine learning algorithms with a multiverse offers untold possibilities of subscribers seamlessly moving between programmes, concerts, shopping and games. Shoshana Zuboff (2019, p. 8) notes that surveillance capitalism “claims human experience as free raw material”, and it is the interplay between binge and pause that offers the potential for future growth on the streaming site. Martinez and Kaun (2019, p. 198) argue for a shift in the study of algorithmic culture from viewers being seen as passive data-gathering opportunities towards an analysis of performative actions, identifying users of Netflix as “active co-creators” of content. While Netflix’s subscription base is believed to have nearly reached saturation during the pandemic, competition is mainly seen with YouTube, Tik Tok and online gaming, so blurring the boundaries between creator and consumer has the potential for users to become “brand evangelists” (Vernalis, 2008, p. 17).

Williams wrote of the “single irresponsible flow” (2003, p. 92) between shows from advertising, station identifiers and trailers of upcoming shows. I wonder whether the “irresponsible flow” now refers to the ease of movement from watching to participating. Netflix recently announced the commissioning of Squid Game 2 alongside the upcoming Squid Game reality show, the biggest competition series ever, with 456 contestants and a prize of $4.56 million. In the press release, Brandon Reigg, Netflix VP of Unscripted and Documentary Series said, “we turn the fictional world into reality” (Netflix News, 2022). Squid Game: The Challenge suggests that the original programme is just the starting point or gateway to a Netflix-verse where the original anti-capitalist sentiments are reimagined as a consumerist taster for wider immersion. Thus, multifaceted viewing encourages breaking from one form of a show to another. Real-life merges with the streaming experience, where shows become their own world, that fans can consume, purchase and live within.

Walter Benjamin’s essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction sets out two distinct positions for the spectator of art as “distraction and concentration” (1935, p. 18). While higher-order art forms (painting, architecture, and music) encourage the viewer to become absorbed in the artists’ skill, nuance and historical reference, Benjamin points to the distracted gaze of popular film, whereby the viewer, shocked by the dissonance of the shifting frame, retains a critical perspective and interprets the art from their own experience. Linked with Bertolt Brecht’s theory of Verfremdungseffekt – often translated as alienation or estrangement, Benjamin’s hope that cinema would become a truly modern art form rested on the elevation of disrupted viewing. Similarly, Joan Hawkins argues that the VCR and remote control “unmoored” the idea that television spectatorship is a lesser form of viewing than cinema, offering technology that encourages Brechtian active viewing (2000). Caetlin Benson-Allott (2021, p. 180) also challenges the notion of cultural inferiority, calling for a “reparative history of distracted viewing”. Picking up the feminist mantle of challenging the ideal of rapt and riveted spectators as the patriarchal canon, Benson-Allott asks, “what’s wrong with the distracted spectator?”. While Netflix controls have hitherto served to break from the programme, the future of Pause may instead drive the viewer deeper, blurring the distinction between watching and not watching. Pause, rather than an interruption, may put streaming spectators in a state of constant multi-tasking, adding layer upon layer of engagement. Disruption within spectatorship may become synonymous with total immersion.

About the author

Leona is a mature part-time PhD student in Film at Exeter University, supervised by Professors Linda Ruth Williams and Fiona Handyside. She has been Head of Film at Northampton High School and is currently teaching Film and Media at Chesterton Sixth Form College in Cambridge. Prior to teaching, Leona was a theatre director at the Royal Court, Royal Shakespeare Company, National Theatre and Artistic Director of Polyglot Theatre Company, which examined the experiences of refugee communities. Productions include The Harvest Plays by Mowes Adem at the National Theatre Summer Festival, Dreams of Anne Frank at Polka Theatre, The Golem and In Extremis at the Young Vic. Leona studied Film, English and Drama at Bangor University, completed an MA in Teaching at Leeds, and a PG Certificate in Applied Drama at Royal Central School of Speech and Drama. Leona is a founding member of the Film/making Education Special Interest Group at BAFTSS. She presented papers on Pause as Progress at the Kings College London PGR conference in June 2021 and on Cancelling the Male Gaze at Fandom Post-#MeToo in Paris in July 2022.

References

Adalian, J. (2018) Inside the Binge Factory. Vulture/New York Magazine. [online] June 11, 2018. Available at: https://www.vulture.com/2018/06/how-netflix-swallowed-tv-industry.html

Alexander, N. (2021) Editor’s Introduction: Rethinking Binge-watching, Film Quarterly, 75(1), pp. 33–34.

Alexander, N. (2021) From Spectatorship to Survivorship in Five Critical Propositions, Film Quarterly, 75(1), pp. 52-57.

Baldwin, R. (2012) Netflix Gambles on Big Data to Become HB of Streaming, Wired. [online] November 29, 2012. Available at: https://www.wired.com/2012/11/netflix-data-gamble/

Benjamin, W. (1935) The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. In: Illuminations, (1969) edited by Hannah Arendt. New York: Schocken Books.

Benson-Allott, C. (2021) The Stuff of Spectatorship. Oakland: University of California Press.

Bourdieu, P. (2010) Introduction to the First Edition. In: Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, London: Routledge.

Bratton, B. (2015) The Stack – On Software and Sovereignty. London: MIT Press.

Brockway, M. (2020) Netflix Launches Immersive Virtual Experience of Original Series in 360, Freegameguide. [online] August 8, 2020. Available at: https://freegameguide.online/2020/08/08/netflix-launches-immersive-virtual-experience-of-original-series-in-360o/

Brunsdon, C. (1986) Women Watching Television. MedieKultur: Journal of Media and Communication Research, 2(4), pp. 100-112. Available at: https://doi.org/10.7146/mediekultur.v2i4.737

Caldwell, J. (2003) Second-Shift Media Aesthetics. In: New Media: Theories and Practices of Digitextuality, edited by Everett, A. and Caldwell, J. London: Routledge, pp. 127-144.

Carson, B. and Roettgers, J. (2021) Playlists and Podcasts? Netflix is Exploring Developing N-Plus, Protocol. [online] May 6, 2021. Available at: https://www.protocol.com/netflix-survey-nplus-show-playlists

Chamberlain, D. (2011) Media Interfaces, Networked Media Spaces and the Mass Customization of Everyday Space. In: Flow TV edited by Kackman, M., Binfield, M., Payne, M., Perlman, A. and Sebok, B. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 13-29.

Chhabra, S. (2017) Netflix Says 80 Percent of Watched Content is Based on Algorithmic Recommendations, Mobilesyrup, [online] Aug 22, 2017. Available at: https://mobilesyrup.com/2017/08/22/80-percent-netflix-shows-discovered-recommendation/

Cubitt, S. (1988) Time Shift: Reflections on Video Viewing, Screen, 29(2), pp. 74–81. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/screen/29.2.74

Davies, R. (2011) Digital Intimacies: Aesthetic and Affective Strategies in the Production and Use of Online Video. In: Ephemeral Media, edited by Grainge, P. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 214-227.

Driscoll, C. (2002) Girls – Feminine Adolescence in Popular Culture and Cultural Theory. New York: Columbia University Press.

Ellis, J. (1994) Visible Fictions, Revised Edition. London: Routledge.

Ellis, J. (2000) Seeing Things – Television in the Age of Uncertainty. London: IB Tauris & Co Ltd.

Fisher-Ogden, P., Zimmer, Kojo and Li. (2015) Netflix’s Viewing Data, The Netflix Tech Blog, [online] January 27, 2015. Available at: https://netflixtechblog.com/netflixs-viewing-data-how-we-know-where-you-are-in-house-of-cards-608dd61077da

Frey, M. (2021) Netflix Recommends – Algorithms, Film Choice and the History of Taste. Oakland: University of California Press.

Friedberg, A. (1993) Window Shopping. London: University of California Press.

Friedberg, A. (2000) The End of Cinema: Multimedia and Technological Change. In: Reinventing Film Studies, edited by Gledhill, C and Williams, L. New York: Bloomsbury, pp. 438-452.

Gauntlett, D. and Hill, A. (1999) TV Living. London: Routledge.

Gomez-Uribe, C. and Hunt, N. (2015) The Netflix Recommender System: Algorithms, Business Value, and Innovation, ACM Transactions on Management Information Systems, 6(4), pp. 1-19. Available at: https://dl.acm.org/doi/pdf/10.1145/2843948

Goode, L. (2017) Netflix is Ditching Five-Star Ratings in Favour of a Thumbs Up, The Verge. [online] March 16, 2017. Available at: https://www.theverge.com/2017/3/16/14952434/netflix-five-star-ratings-going-away-thumbs-up-down

Hallinan, B. and Striphas, T. (2016) Recommended for You: The Netflix Prize and the Production of Algorithmic Culture, New Media & Society. 18(1), pp. 117-137. Available at: https://journals-sagepub-com.uoelibrary.idm.oclc.org/doi/pdf/10.1177/1461444814538646

Hawkins, J. (2000). Cutting Edge: Art-Horror and the Horrific Avant-garde (NED-New edition). University of Minnesota Press.

Horeck, T. (2021) Netflix and Heal: The Shifting Meanings of Binge-watching During the Covid-19 Crisis. Film Quarterly, 75(1), pp. 35–40.

Jebara, T. (2019) Machine Learning for Personalization, ECE Seminar Series: Modern Artificial Intelligence. YouTube. [online] February 28, 2019. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bebNv-wSqt4

Jenkins, H (2008) Convergence Culture – Where old and new media collide. London: NYU Press.

Jenner, M. (2018) Netflix & the Re-invention of Television. Netherlands: Palgrave Macmillan.

Jenner, M. (2021) Introduction. In: Binge-Watching and Contemporary Television Studies, edited by Jenner, M. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. pp. 1-19.

Johnson, C. (2022) Looking Back on the Origin of ‘Skip Intro’ Five Years Later’ Netflix News. [online] March 17, 2022. Available at: https://about.netflix.com/en/news/looking-back-on-the-origin-of-skip-intro-five-years-later

Kompare, D. (2005) Rerun Nation – How Repeats Invented American Television. Abingdon: Routledge.

Kuhn, A. (1984) Women’s Genres – Melodrama, Soap Opera, and Theory. In: Feminist Television Criticism: A Reader (2008), edited by Brunsdon, C. and Spigel, L. Croydon: Open University Press. pp. 226-234.

Littler, J. (2018) Against Meritocracy: Culture, Power and Myths of Mobility. London: Routledge.

Lövheim, M. (2011) Young Women’s Blogs as Ethical Spaces, Information, Communication and Society 14(3), pp. 338–354. Available at: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/pdf/10.1080/1369118X.2010.542822

Martinez, D. and Kaun, A. (2019) The Netflix Experience. In: Netflix at the Nexus, edited by Plothe, T. and Buck, A. Oxford: Peter Lang. pp. 197-211.

McAlone, N. (2017) The Exec Who Replaced Netflix’s 5-Star Rating System with ‘Thumbs Up/Thumbs Down’ Explains Why, Insider. [online] April 5, 2017. Available at: https://www.businessinsider.com/why-netflix-replaced-its-5-star-rating-system-2017-4?r=US&IR=T

Metz. C. and Guzzetti, A. (1976) The Fiction Film and Its Spectator: A Metapsychological Study, New Literary History, 1976, 8(1), Readers and Spectators: Some Views and Reviews pp. 75-105. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/468615.pdf?refreqid=fastly-default%3A9ff45e8b67034e33f93471b5ff24980b&ab_segments=0%2Fbasic_search_gsv2%2Fcontrol&origin=search-results

Meyrowitz, J. (2009) We Liked to Watch: Television as Progenitor of the Surveillance Society, Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, pp. 32-48. Available at: https://search-ebscohost-com.uoelibrary.idm.oclc.org/login.aspx?direct=true&db=edshol&AN=edshol.hein.cow.anamacp0625.4&site=eds-live&scope=site

Mittell, J. (2015) Complex TV: The Poetics of Contemporary Television Storytelling. London: New York University Press.

Morley, D. (1986) Family Television – Cultural Power and Domestic Leisure. London: Routledge.

Morley, D. (2004) At Home with Television. In: Television After TV: Essays on a Medium in Transition, edited by Spigel, L. and Olsson, J. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 303-323.

Netflix News (2022) Announcement: Netflix Greenlights ‘Squid Game: The Challenge’ Reality Competition Series, June 14, 2022. Available at: https://about.netflix.com/en/news/netflix-greenlights-squid-game-the-challenge-reality-competition-series

Netflix Q2 (2021) Letter to Shareholders. Available at: https://s22.q4cdn.com/959853165/files/doc_financials/2021/q2/FINAL-Q2-21-Shareholder-Letter.pdf

Ofcom Media Nations UK 2021 [online] Published August 5, 2021. Available at: https://www.ofcom.org.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0023/222890/media-nations-report-2021.pdf

Robinson, M. J. (2017) Television on Demand. London: Bloomsbury.

Rushe, D. and Lee, B. (2020) Netflix Doubles Expected Tally of New Subscribers Amid Covid-19 Lockdown’. The Guardian Online, April 21. Accessed on: https://www.theguardian.com/media/2020/apr/21/netflix-new-subscribers-covid-19-lockdown

Silverstone, R. (1994) Television and Everyday Life. London: Routledge.

Simon, J. (2021) Introducing Netflix.shop: A New Way for Fans to Connect with their Favorite Stories, Netflix.com. [online] June 10. Available at: https://about.netflix.com/en/news/introducing-netflix-shop

Spigel, L. (1988) Installing the Television Set: Popular Discourse on Television and Domestic Space, 1948-1955. In: Private Screening (1992), edited by Spigel, L. and Mann, D. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. pp. 3-38.

Strangelove, M. (2015) Post-TV: Piracy, Cord-Cutting, and the Future of Television, Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Sweet, A. (2018) Hooked on Orange is the New Black? In: Combining Aesthetic and Psychological Approaches to TV Series Addiction, edited by Camart et al. Newcastle: Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 167-180.

Tasker, Y. and Negra, D. (2007) Introduction. In: Interrogating Postfeminism – Gender and the Politics of Popular Culture, edited by Tasker, Y. and Negra, D. London: Duke University Press.

Tryon, C. (2015) TV Got Better: Netflix’s Original Programming Strategies and Binge Viewing, Media Industries, 2(2). Available at: https://doi.org/10.3998/mij.15031809.0002.206

Tussey, E. (2014) Connected Viewing on the Second Screen: The Limitations of the Living Room. In: Connected Viewing: Selling, Streaming & Shared Media in the Digital Era, edited by Holt, J. and Sanson, K. Abingdon: Routledge, pp. 202-216.

Uricchio, W. (2004) Television’s Next Generation. In: Television After TV, edited by Spigel, L. and Olsson, J., Durham, N. C.: Duke University Press. pp. 163-182.

Uricchio, W. (2009) Contextualizing the Broadcast Era: Nation, Commerce, and Constraint, The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 625. pp. 60-73. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/40375905?seq=1

Vernalis, K. editor (2008) Networked Publics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Williams, R. (2003) Television: Technology and Cultural Form. Abingdon: Routledge.

What’s on Netflix (2021) List of Netflix Categories, What’s on Netflix. Available at: https://www.whats-on-netflix.com/library/categories/

Zuboff, S. (2019) The Age of Surveillance Capitalism. London: Profile.

Zucosky, A. (2021) Fortnite’s Ariana Grande Concert Brings Humanity to the Metaverse, Digital trends. [online] August 6. Available at: https://www.digitaltrends.com/gaming/fortnite-rift-tour-ariana-grande-concert/

Zündel, J. (2019) TV IV’s New Audience. In: Netflix at the Nexus, edited by Plothe, T. and Buck, A. Oxford: Peter Lang. pp. 13-27.

Filmography

Black Mirror – Bandersnatch. December 28, 2018. (Television episode) UK: Netflix.

Bridgerton. 2020-present. (Television series) UK: Netflix.

Emily in Paris. 2020-present. (Television series) USA: Netflix.

Grey’s Anatomy. 2005-present. (Television series) USA: Buena Vista Television, Disney-ABC Domestic Television.

Jurassic World. 2015. (Film) Colin Trevorrow. dir. USA: Universal Pictures

Parks & Recreation. 2009-2015. (Television series) USA: NBC Universal Television.

Queer Eye. 2018-present. (Television series) USA: Netflix.

Ratatouille. 2007. (Film) Brad Bird. dir. USA: Walt Disney Pictures.

Riverdale. 2017-present. (Television series) USA: Warner Bros Television.

Squid Game. 2021-present. (Television series) South Korea: Netflix.

Stranger Things. 2016-present. (Television series) USA: Netflix.

The Big Bang Theory. 2007-2019. (Television series) USA: Warner Bros Television.

The Crown. 2016-present. (Television series) UK/USA: Netflix.

The Half of It. 2020. (Film) Alice Wu. dir. USA: Netflix.

The Holiday. 2006. (Film) Nancy Meyers. dir. USA: Columbia Pictures.

The Kissing Booth 2. 2020 (Film) Vince Marcello. dir. USA: Netflix.

Tiger King. 2020-2021. (Television series) USA: Netflix.

Unbreakable Kimmy Schmidt – Kimmy vs the Reverend. May 12, 2020 (Television episode) USA: Netflix