Make Yourself at Home: Home Studios as Pedagogical Practice

Pamela Whitaker and Christopher McHugh

Download the PDF of this article

ISSN 2752-3861

Make Yourself at Home

This is a case study of a joint teaching venture between the subject areas of ceramics and art psychotherapy at the Belfast School of Art, that situates making at home as a centrepiece for pedagogical practice.

The article features a literature review with correspondences to art and design pedagogical theories and material culture theories. The co-teaching partnership between ceramics and art psychotherapy centred on the delivery of group reflective practice, which is an essential component of professional development for trainee art psychotherapists. Reflective practice is a foundation for self and professional inquiry within art psychotherapy that incorporates visual narrations of self-awareness and psychological mindedness.

The aim of group reflective practice is art making for self-care and critical insight to support art psychotherapy trainees in practicum modules. Group reflective practice is supported by visits to Belfast School of Art studios across a variety of disciplines. The reference to group refers to a cohort of twenty art psychotherapy students creatively responding to material opportunities for multivalent learning that integrates self and practitioner (Mulholland, 2019). The ceramics studio is particularly relevant in regard to studying material culture and how it narrates associations to objects that are both near and dear to us. This domestic focus on reflective practice enhanced self and professional awareness for art psychotherapy trainees. The emphasis on found and readily available materials promoted sustainability in terms of making the most of what is available, while also developing professional proficiencies related to adaptability and ingenuity.

The topic of material culture developed added significance during distance learning at home, as it associated to materials that were already lived with in the form of personal belongings. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the art psychotherapy and ceramics courses at Belfast School of Art regularly collaborated on the development of joint pedagogic resources for the on-campus teaching of ceramics. There was a natural affinity between the two subject areas due to the historical use of clay as a therapeutic medium and shared research and pedagogic interests relating to personal belongings. Although remote and distanced, this learning and teaching endeavour aimed to encourage a sense of community and communication, allowing participants to share and present their work online. Distance learning offered an opportunity to be in proximity with the cultures of each other’s homes in terms of their distinctions and divergences.

During COVID-19 restrictions the art psychotherapy and ceramic studios at Belfast School of Art combined to support making within the domestic home studio. This pedagogical inquiry explored the art of the everyday. The belongings of home were found, curated, and assembled as a collection that had relevance as a personal archive. This was art production with the already made and at hand. It offered an opportunity to create home displays which featured students’ annals of materiality. As a form of collaborative teaching its significance was linked to reimagining pedagogic pathways of production. It encouraged representation of cultural diversity through a display of objects that meant something to the owner as life materials (Campbell, 2017).

An integral aspect of the project was the communal display of home assemblages. Although initially this was done online through screen sharing, it was possible later to mount a celebratory display on campus. It is increasingly recognized that curated displays can have affective potential. As affect comes from an initial response to something, it can perhaps be likened to conceptions of wonder and contextual resonance (Greenblatt, 1991). Affect and wonder can be harnessed in displays to “enable people to reflect creatively, sometimes transformatively, on themselves and others” (Dudley, 2010, p.3).

Object and material based learning is an essential component of art psychotherapy training and art and design education. Foraging and rummaging can be an expression of creative thinking, physical action and imaginative reverie (Woodall, 2015). Sharing life at home brought students together on gallery view. Their object assemblages were an example of relational aesthetics (Bourriaud, 2002) and the creative practice of the everyday (de Certeau, 1988).

This interdisciplinary collaboration (between art psychotherapy and ceramics) placed the materials of living centre stage. As a signature art psychotherapy pedagogy, making at home with objects of lived experience, is a self-determined arts-based inquiry or heutagogy in action (Leigh, 2020; Collis, 2021). Heutagogy promotes learner centric experiential learning, relevancy and purpose and within art and design education it can formulate homemade studio practices (Collins, 2021).

The Home Studio

Make Yourself at Home, is a pedagogical project that distinguishes students as experts by experience in their own specific artist residency (their home). The readymades of the home environment are accessible and relatable. Rather than making something new, the surroundings of home are inherently one’s own and therefore bespoke and culturally specific. The home as studio also develops professional correspondences for art psychotherapy trainees, who consider their life materials to be relevant for reflecting upon their clinical practicums. Their use of subjectivity informs their capacity to professionally formulate alliances to the home stories of their clients.

This article also highlights sustainability through the use of found and repurposed art materials. It illustrates social inclusion through materiality, in terms of each student utilising the materials that best represent their specific identities. In this capacity the article also contributes towards UN Sustainable Development Goals related to wellbeing, reduced inequalities, and responsible consumption (United Nations, 2015). Student curated home displays are autobiographical experiences, relating to the comfort of home (Miller 2008) and a range of personal contexts, memories and associations. As an expression of responsible consumption and production, making with belongings reduces dependence on bought materials and the potential of excess waste.

Purchased art materials are prevalent and persuasive within art education and add to the burden of both student financial expense and unnecessary consumption. Art production, with materials that align with a student’s identity choices, enhance inclusion by supporting a learner’s representation. Personalised materials can be found at home that support a form of material equity—each student accessing what expresses their best interests. In this model, the educator doesn’t assign the materials of use, but rather encourages learners to find their creative resources with what they already possess

Where we Belong

The home is an intimate space where “belonging, privacy and familiarity” develop through the accrual of material culture (Lipman, 2019, pp. 84-85) representing the lived and inherited experiences of the occupiers. This becomes an archive of the lives of the inhabitants, a palimpsest of spatio-temporal contexts which coexist as “lingering layers of a collective shaping of home” (Lipman, 2019, p. 87). The act of displaying this material to form a discursive narrative is a form of personal heritage, a “creative production involving the assembly and reassembly of things on the surface and in the present” (Harrison, 2013, p. 227). This can be an empowering process of reminiscence, where disparate elements are curated to form a palatable output which can be shared with others in a communicable way (Arigho 2008).

Reimagining the significance of our belongings, contributes to diversity education in the way that possessions represent their owners in distinctive ways. These are not particular materials assigned for coursework, but rather materials that already exist in the bricolage of a learner’s homeplace. These are consequential objects that may be comforting and reassuring or associated to clutter as a mélange of material miscellany. The bits and pieces of our lives are brought together as an assembly that associates to storytelling. These items may be a combination of functional objects, bric-a-brac, heirlooms, trinkets, souvenirs, handmade artworks and the ephemera of possessions in general—no object is excluded, and all material contributions are welcome in the production of home.

Materiality conveys meaning. It provides the means by which social relations are visualised, for it is through materiality that we articulate meaning and thus it is the frame through which people communicate identities. Without material expression social relations have little substantive reality, as there is nothing through which these relations can be mediated. (Sofaer, 2002, p. 1)

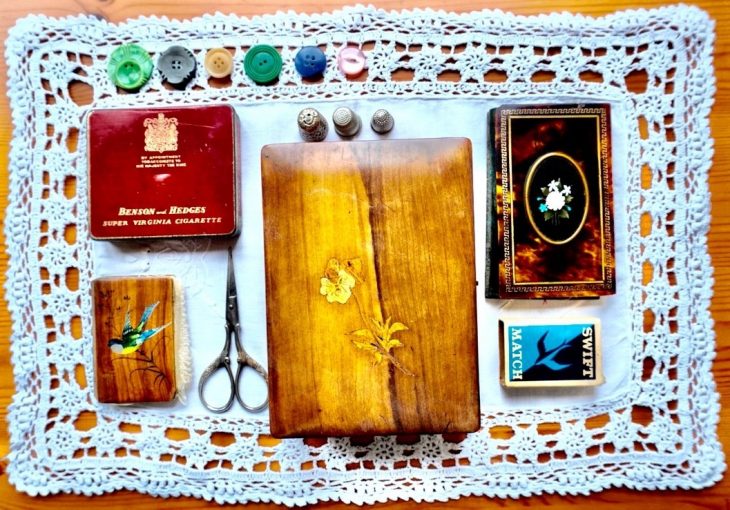

The material culture of everyday life at home has a relationship to each person’s design history in terms of what they have bought, inherited and made (Attfield, 2000) (Figure 1). Our conglomerate arrangements of things are selectively revealed and transgress the boundary between a private domestic space and a public online presence. This was an endeavour that acted as a form of artist collective, where students communicated through their object relations. A community of artistic practice (Wenger-Trayner and Wenger-Trayner, 2015) was formed whereby each contributor brought something, not only to their own table, but to the online tablescape (the gallery view of table installations). Found objects from many homes aligned as one shared exhibition. The authors propose that this method of pedagogy is well suited to cultural production disciplines as a way to represent the complexity of learner’s cultural and material associations (Bridgstock, 2019).

Artists in Residence

Home based displays are curatorial and can form an educational centrepiece, a focal point for considering object relations. No two homes are the same, and what we do with the materials therein can be attributed to a bespoke agency of expression. Through their arrangement and constancy, the materials of home provide something to hold on to in times of uncertainty. Personal items offer “ontological security” (Olsen 2010, p. 160) in their association to storytelling. At a time when learning and teaching were mediated virtually, the home studio become a place of resourcefulness.

The materials of life were readily available to learners as artists in their own residence. As an example of repurposed artistry, using materials at hand honours the vernacular culture of home. For art psychotherapy trainees this methodology was also applicable to their practicum work with clients in a variety of clinical and community contexts. Rather than art psychotherapy trainees deciding which materials are brought to the table, their clients can be invited to bring what they need from home. As artists in their own residence art psychotherapy service users are familiar with what matters in terms of their meaningful possessions.

The resources of home can act as an autobiography of references that scaffold ordinary activities. As support structures they are a bespoke collection of one’s self. Support “transforms the perception of things” (Condorelli, 2009, p.11) into relationships that hold significance in their common cause of working together. Assembling materiality composes an environment of allegiances that are connected to need. “Support’s first operational feature is proximity. No support can take place outside a close encounter, getting entangled in a situation and becoming implicated in it” (Condorelli, 2009, p.15). Indeed, the temporary associations of domestic found objects opens up possibilities for rearrangement and the potential of continued re-creation.

Anthropologist Alfred Gell’s (1998) work on assemblages offers a convincing way of understanding how the things we make and own may serve to extend our agency. Gell proposed a close relationship between the internal cognitive world of the artist and the way it is materialised externally as the artist’s oeuvre of distributed objects (Gell, 1998). Here, people are not confined to the spatial or temporal limits of their body, “but consist of a spread of biographical events and memories of events, and a dispersed category of material objects, traces and leavings” (Gell, 1998, p. 222). Materials are a testimony and history of lived experience (Figure 2). Jane Bennett’s conception of assemblages may also be helpful in attempting to understand the multifarious ways in which assemblages are construed as “ad hoc groupings of diverse elements [acting as] living throbbing confederations” (Bennett, 2010, pp. 23-24).

The ‘at-hand’ (Levi-Strauss, 1966) materials of home are more diverse and heterogeneous than the substance of clay, and by encouraging the methods of assemblage, bricolage and collage, the project explored “flexibility and plurality” (Rodgers, 2012, p.1). The use of assemblage imbues artworks with multiple layers of meaning. According to Diane Waldman (1992, p. 11) these associations emerge from “the original identity of the fragment or object and all of the history it brings with it; the new meaning it gains in association with other objects or elements; and the meaning it acquires as the result of its metamorphosis into a new entity” (Figure 3).

Home Schooling

A home production ethos of teaching and learning can bestow creative learning graduates with the agency to develop portfolio careers that contribute to the arts, arts and wellness, and social inclusion policies which add to quality-of-life initiatives (Bridgstock, 2019). As creative learners, school of art graduates utilise interdisciplinary skills for adaptability and transferability to health and creative industries. The capacity to integrate diverse ways of thinking and doing is essential in relation to design thinking for the production of objects and services (Brown, 2019).

Through material journaling, each student is a researcher in their own territory and documents their discoveries as a living method (Orr, Yorke and Blair, 2014). As educators we should encourage response-ability to the material stories brought to us through the stuff of life—enacting a duty of care to learners who are exhibiting themselves through their home displays (Sajnani, N., Marxen, E. and Zarate, R., 2017). By way of facilitation, educators can make meaningful what is already present (and becoming) in a student’s reflective practice through a framework of engagement, and reciprocal making. In response to the student’s own life production project there is a co-creation of knowledge and the generation of educator and learner identities in process. The legitimacy of knowledge is contextualised to the specifics of what is inherently and intrinsically known by learners who formulate a curriculum in the making, that also educates the educator (Healey, Matthews and Cook-Sather, 2020).

Neil Mulholland (2019) refers to collective learning in art schools as paragogy, an artistic community of practitioners supporting each other in the achievement of their creative productions. The online home studio is both intrinsically personal and also a formation of an artist collective within its sharing within a gallery view. The immanence of the home studio is accessible to others online, and the camera viewpoint is the portal for open house viewing. Mulholland considers the studio to be an internal consideration of making in situ. A studio can be anywhere in the home, designated through intention and curation and impromptu assembly. Making with objects found at home, reconceptualises studios as not necessarily being set apart from the activities of domestic life. A studio therefore can be designated by what is all around us—what we live with and use as possessions. The use of domestic objects, their availability and their narratives (that range from function to symbolic value) are placed together as representations of inclusivity. There is a humility in the exposure of both home and belongings.

Orr and Shreeve (2018) highlight the role of ambiguity within art and design education when studio education is co-created and delivered as a multi-disciplinary set of skills and contextual learning. The breadth of art and design education encompasses identity transformation and the inclusion of life experiences which inform artist identities in production. “The art and design curriculum is a complex web of activities in which students forge a way to becoming a creative practitioner” (Orr and Shreeve, 2018, p. 7). The curriculum of art and design has a sensory response related to what Orr and Shreeve (2018) describe as stickiness, which is associated to uncertainty and working in an immersive way with materials and environments. The sticky curriculum denotes “the fluid roles of learner and teacher” (Orr and Shreeve, p. 14) as aligned creative practitioners. The stickiness here refers to the co-production of artistic identities through shared art making, so that the distinction between educator and learner is a bonding rather than a detachment.

Fit for Purpose

Within art psychotherapy working with readymades is repurposing potentially discarded, rejected or lost personal memories and experiences (Figure 4). Each object has a history and an association to its owner and its reuse is an example of adaptability and a psychological bridge to this attribute within life (Brooker, 2010). It offers an opportunity to reconstitute—to put ourselves in order and hold ourselves together through metaphors that creatively reconfigure ourselves in tangible forms (Wong, 2021). In this way mental space is curated along with the contents of physical space (Lefebvre, 1991).

The joint productive activity of learners and educators expresses the wisdom of both in a dialectical material conversation (Backos and Carolan, 2017). There is a collaborative responsibility to orchestrate the environment and recognise multiple forms of emergent knowledge (Backos and Carolan, 2017). Gerber (2016) concurs with the significance of different cultural realities informing art psychotherapy pedagogy through a pluralistic ontology. She emphasises the importance of intersubjectivity within contextual variables (different kinds of homes and materials therein) that construct a materiality of learning that is intentional, dialectical and a witnessing of difference. The intersubjective matrix is an aesthetic pedagogy that assembles a bricolage of art production.

Within the creative dialectical space, students are encouraged to deconstruct, reconstruct and synthesise multiple forms of knowledge, be open and receptive to emergent knowledge,….cultivate curiosity and imagination, develop the capacity to engage in self and self/other exploration and to develop therapeutic emotional presence. (Gerber, 2016, p. 798)

Found objects are conduits for creative environmental actions that “explain, expand, enable, remind, relate and relive aspects of past and current lives” (Camic, Brooker, and Neal, 2011, p.157). They can “extend the self to allow us to do something we would otherwise be incapable of: as mechanisms to aid the enhancement of personal power; to help us know who we are by observing what we have; and by enlarging our sense of self” (Camic, Brooker and Neal, 2011, p. 152). As mementos of associative symbolic experiences, objects identify both a personal and professional portrait. What is personal becomes the foundation for a professional identity as a form of adaptation and re-use. Object relations can infuse professional identity with a cultural affiliation to our home base as the foundation for our professional portrayal. Home care is the basis by which to begin a process of professional learning that transforms domestic materials into a professional signature.

Objects distinguish personal and professional territories and therefore are applicable within the home studio as a pedagogical reference. The home milieu elicits representations of material becomings that form educational and professional production. Home is an architectural frame for making that asserts an imperative to organise; it constitutes a compositional plane that offers a “provisional ordering of chaos” (Grosz, 2008, p. 13). Grosz elaborates that without a framework or boundary “there can be no territory, and without territory there may be objects or things but not qualities that can become expressive, that can intensify and transform living bodies (Grosz, 2008, p.11). Mulholland (2019) asserts that paragogy facilitates peer-focussed learning theories that are heterogenous and therefore culturally relevant to the learner. Each home is a bespoke learning environment that engenders diversity and a complexity of artistic homemaking. “Difference is thus key. An assembly of peers benefits from their own diversity” (Mulholland, 2019, p. 105).

Art psychotherapy trainees at the Belfast School of Art described making at home as a visual narrative, whereby their belongings represented both a past and an arrangement of material stepping stones to the future. The terms bricolage, assemblage, tableau and arrangement were evoked in personalised ways depending upon a student’s objects of kinship (how their objects related to one another).

Working with found objects was a way to re-frame the viewing of home spaces so that they seamlessly combine in terms of functionality and artistry to form a whole. An installation composed of possessions offers proximity, designation and the opportunity to exhibit home possessions that are at hand. Distance learning, rather than separation, cultivated an enhanced form of relating based on the entanglement of things as entities that extended from one homeplace to another (Hodder, 2012).

Our Place at the Table

The community table is a methodology of practice within art psychotherapy that distinguishes the in-between as a location of creative endeavour (Lloyd and Usiskin, 2022). It is an approach to art making that transgresses boundaries and borders of personal territories. It is relevant to consider in terms of producing a mediating space between the private lives of learners and teachers online. It incorporates the role of the impromptu or improvised studio at home, and the portable studio as a “relational connection” (Lloyd and Usiskin, 2022, p. 105). Lloyd and Usiskin appeal to art therapists “to look beyond traditional art materials and practices that might lack cultural relevance” and adopt instead the materials that are already part of people’s lives (Lloyd and Usiskin, 2022, p. 106).

Inviting people from outside our home into our domestic life is both a risk and an expression of hospitality. Everyone can be affiliated through their displays of belongings, visualised through an online gallery view, so that “home space and art psychotherapy space combined collectively” (MSc Art Psychotherapy trainee, 2022, personal communication). Homemaking is a communal opportunity—“we pieced ourselves together and became familiar through virtually associating with each other’s belongings” (MSc Art Psychotherapy trainee, 2022, personal communication). The juxtaposition of possessions produces a social network whereby everyone has a place at the table (Figure 6).

The perception of mind as a personal archive, or collection, can be represented in site-specific installations that act as symbolic holding environments. Tableaus remind us of what we bring to the table in terms of autobiographical objects and the occasion of the present (Silver, 2015). As an ordering of knowledge and a collation of ideas, the Make Yourself at Home collection is a repository of associations that position a whole from sensorial material metaphors (Silver, 2015). The home environment holds together details and components of subjectivity. It creates a topographical field of consistency, which coordinates an intensity of affects and a juxtaposition of the familiar (Frichot, 2006; Dewsbury and Thrift, 2006). The study of home was considered by Bachelard to be a topoanalysis, or the “systematic psychological study of the sites of our intimate lives” (Bachelard, 1964, p. 8).

In Closing

Make Yourself at Home is a pedagogy of artist collectivity that materialises identities through inclusive and engaged co-production. It is a contribution to diversity education, peer learning communities and self-determined learning. It originated as an artistic practice within distance learning facilitated as a ceramics informed presentation of material culture studies, but has subsequently been utilised within art psychotherapy practicums facilitated by students. Installations, composed of found objects, are personally significant to learners as bespoke forms of curatorial arrangements and material memoirs. The sustainability of repurposing what is at hand develops resourcefulness and adaptability both artistically and professionally.

This collaborative venture between ceramics and art psychotherapy was forged online, but subsequently influenced on-campus teaching in the way that belongings became a resource for clinical training. It is a privilege to be invited into the homes of students as combined artistic practitioners. In this regard the distinction between home and studio is challenged. So too is the idea that art production necessarily refers to the making of something new. The art school can support an ethics of multiple use (versus single use) to endorse repurposing as a sustainable imperative. Art education should evoke the origins of the word university, referring to both incorporation or corporatus (in this context the shared dwelling of being at home and becoming a collective of homebodies) and universitas (the sharing of endeavour and the making of community) (Mulholland, 2019).

Everyone can be a curator in their own homes and appreciate what they already have as being enough. Rather than making in excess, there is a consolidation of the already there and the artistic practice of the everyday. Forming an assemblage of personal symbols is a way of learning whereby everyone has a contribution based on distinct affiliations represented by their bespoke domestic materials. Although this model of studio practice originated in distance learning, it has since been applied to art psychotherapy trainee practicums in a variety of counselling, school and mental health settings. Making people feel at home, with what they have at home, acknowledges the significance of personalised materials to inform artistic and professional practices in art psychotherapy for both trainees and art psychotherapy service users.

A home collection can be considered a personal gallery dedicated to a person’s legacy of object relations. Objects are survivals of the past that endure as historical artefacts and commemorations (Stocking, 1985). An object within online teaching, encompasses both private and public spaces and the staging of ourselves in a public homeplace (Timm-Bottos, 2012). A homemade curio display performs a therapeutic landscape or restorative sense of place making. Our objects represent a dynamic materiality that can be shaped and creatively reconfigured through physical and sensory routes of experience. The object palette as a sensory and therapeutic landscape associates to symbolic dimensions of place (Bell, et al., 2018). The homeplace as a health and therapeutic terrain holds significance in its positioning as an everyday reality. The ordering and arrangement of objects creates a composition for self-care and reflection (Bell, 2018). Our material arrangements are multi-faceted and multi-directional and can be simultaneously an artistic production, educational practice and career affiliation.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Lauren Kwant, Heidi Kwant and Finlay McConnell for creating and photographing their home displays for this article.

About the authors

Pamela Whitaker is a lecturer in art psychotherapy at the Belfast School of Art, Ulster University. She encourages the curation of personal possessions as both a pedagogical and therapeutic approach to creating with what is at hand. She produces publications and events which endorse art therapy within festivals, outdoor environments and cultural venues as a form of public and engaged practice. She also facilitates creative health initiatives within galleries and museums and encourages the art of gatherings within community gardens.

Dr Christopher McHugh is Lecturer in Ceramics and Global Engagement Lead at Belfast School of Art, Ulster University, UK. His practice-led ceramics research explores the relationship between making and wellbeing, often focusing on archives, museum collections and communities.

References

Arigho, B. (2008) Getting a handle on the past: The use of objects in reminiscence work. In H. Chatterjee, ed. Touch in museums: Policy and practice in object handling. New York: Berg, pp. 205-212.

Attfield, J. (2000) Wild Things: The material culture of everyday life. Oxford: Berg.

Bachelard, G. (1964) The poetics of space. Boston: Beacon Press.

Backos, A. and Carolan, R. (2017) Art therapy pedagogy. In: R. Carolan and A. Backos, eds. Emerging perspectives in art therapy: trends, movements and developments. London: Routledge, pp. 48-57.

Bell, S.L., et al. (2018) From therapeutic landscapes to healthy spaces, places and practices: A scoping review. Social Science and Medicine, 196, pp. 123-130.

Bennett, J. (2010) Vibrant matter: a political ecology of things. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Bourriaud, N. (2002) Relational aesthetics. Dijon: Les Presses du Réel.

Bridgstock, R. (2019) Creative industries and higher education: what curriculum, what evidence, what impact? In: Cunningham, S. and Flew, T, eds. A research agenda for creative industries. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing, pp. 112-130.

Brooker, J. (2010) Found objects in art therapy. International Journal of Art Therapy 15 (1), pp. 25-35.

Brown, T. (2019) Change by design. New York: Harper Collins Publishers.

Camic, P., Brooker, J. and Neal, A. (2011) Found objects in clinical practice: Preliminary evidence. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 38, pp. 151-159.

Campbell, L. (2017) Collaborators and hecklers: Performative pedagogy and interruptive processes. Scenario: Journal for Performative Teaching, Learning, Research, 7 (1), Available from: https://journals.ucc.ie/index.php/scenario/article/view/scenario-11-1-5/html-en [Accessed 19 June 2022].

Cohen, J. J. (2015) Stone: An ecology of the inhuman. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Collis, A. (2021) Heutagogy in action: An action research project in art education. In S. Hase and L. M. Blaschke eds. Unleashing the Power of Learner Agency. EdTech Books, https://edtechbooks.org/up/art

Condorelli, C. (2009) Directions for use. In: Condorelli, C., ed. Support structures. Berlin, Sternberg Press, pp. 9-22.

de Certeau, M. (1988) The practice of everyday life. Berkley, CA: University of California Press.

Deleuze, G. and Guattari, F. (2004) A thousand plateaus: Capitalism and schizophrenia. London: Continuum Press.

Dewsbury, J.D. and Thrift, N. (2006) Genesis eternal: after Paul Klee. In: Buchanan, I. and Lambert, G., eds. Deleuze and space. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 89-109.

Dudley, S. (2010) Museum materialities: Objects, sense and feeling. In: S. Dudley, ed. Museum materialities: Objects, engagements, interpretations. New York: Routledge, pp. 1-17.

Farebrother, R. (2016) The collage aesthetic in the Harlem renaissance. London: Routledge.

Frichot, H. (2006) Stealing into Gilles Deleuze’s baroque house. In: Buchanan, I. and Lambert, G., eds. Deleuze and space. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 61-80.

Gerber, N. (2016) Art therapy education: A creative dialectical intersubjective approach. In: D. Gussak and M. Rosal, eds. The Wiley Handbook of Art Therapy. Chichester, West Sussex: John Wiley and Sons, pp. 794-802.

Greenblatt, S. (1991) Resonance and Wonder. In. I. Karp and. S.D. Lavine, eds. Exhibiting cultures: The poetics and politics of museum display. Washington: Smithsonian Institution Press, pp. 42–57.

Grosz, E. (2008) Chaos, territory, art. New York: Columbia University Press.

Harrison, R. (2013) Heritage: Critical approaches. London: Routledge.

Healey, M., and Matthews, K.E., and Cook-Sather, A. (2020) Writing about learning and teaching in higher education. Elon, NC: Elon University, Centre for Engaged Learning. Available from: https://www.centerforengagedlearning.org/books/writing-about-learning/ [Accessed 5 June 2022].

Hodder, I. (2012) Entangled: An archaeology of the relationship between humans and things. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell.

Ingold, T. (2013) Making: anthropology, archaeology, art and architecture. London: Routledge.

Irwin, R. (2022) A/r/tography: An invitation to think through making, researching, teaching and learning. Available from: https://artography.edcp.educ.ubc.ca [Accessed 19 June 2022].

Lefebvre, H. (1991) The production of space. Oxford: Blackwell.

Leigh, H. (2020) Signature pedagogies for art therapy education: A Delphi study. Art Therapy: Journal of the American Art Therapy Association. 38 (1), pp. 5-12.

Levi-Strauss, C. (1966) The savage mind. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

Lipman, C. (2019) Living with the past at home: The afterlife of inherited domestic objects. Journal of Material Culture, 24 (1), pp. 83-100.

Lloyd, B. and Usiskin, M. (2022) The community table: Developing art therapy studios on, in-between, and across borders. In: Brown, C. and Omand, H., eds. Contemporary practice in studio art therapy. London: Routledge, pp. 101-117.

Malis, D. (2021) The aesthetics of touch; discovering the embedded potential of found objects as a pedagogical platform. In: Wong, D. and Lay, R., eds. Found objects in art therapy: Materials and process. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, pp. 195-212.

Miller, D. (2008) The comfort of things. Malden, MA; Cambridge: Polity Press.

Mulholland, N. (2019) Re-imaging the art school: Paragogy and artistic learning. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

Olsen, B. (2010) In defense of things: archaeology and the ontology of objects. Plymouth: Altamira Press.

Orr, S. and Shreeve, A. (2018) Art and design pedagogy in higher education: Knowledge, values and ambiguity in the creative curriculum. London: Routledge.

Orr, S., Yorke, M. and Blair, B. (2014) The answer is brought about within you: A student-centred perspective on pedagogy in art and design. International Journal of Art and Design, 33 (1), pp. 32-45.

Rodgers, M. (2012) Contextualizing theories and practices of bricolage research. The Qualitative Report, 17, T&L Art 7, pp. 1-17.

Sajnani, N., Marxen E. and Zarate, R. (2017) Critical perspectives in the arts therapies: Response/ability across a continuum of practice. The Arts in Psychotherapy, 54, pp. 28-37.

Silver, S. (2015) The mind as a collection. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Sofaer, J. (2007) Introduction: Materiality and identity. In Sofaer, J., ed. Material identities. Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, pp. 1-11.

Stocking, G.W. (1985) Essays on museums and material culture. In: Stocking, G.W. ed. Objects and others: Essays on museums and material culture. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, pp. 3-14.

Teaching to Transgress Toolbox (2022) Available from: http://ttttoolbox.net/#about [Accessed 25 June 2022].

Timm-Bottos, J. (2012) The five and dime: Developing a community’s access to art based research. In: Burt, H., ed. Art therapy and postmodernism: Creative healing through a prism. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, pp. 97-118.

Turkle, S. (2007) Evocative objects: Things we think with. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

United Nations (2015). Sustainable goals. https://sdgs.un.org/goals.

Waldman, D. (1992). Collage, assemblage, and the found object. London: Phaidon.

Wenger-Trayner, E. and Wenger-Trayner, B. (2015) Introduction to communities of practice.

Available from: https://wenger-trayner.com/introduction-to-communities-of-practice/ [Accessed 5 June 2022].

Whitelaw, J. (2021) Collage praxis: What collage can teach us about teaching and knowledge generation. Journal of Language and Literacy Education, 17 (1), pp. 1-23.

Woodall, A. (2015). Rummaging as a strategy for creative thinking and imaginative engagement in higher education. In: Chatterjee, H. and Hannan, L., eds. Engaging the senses: Object based learning in higher education. Ashgate Publishing, pp. 133-159.

Wong, D. (2021) Materials: Potential and found objects. In: Wong, D. and Lay, R., eds. Found objects in art therapy: Materials and process. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers, pp. 25-39.