Audio Artists Assemble!: Designing a Creative Pedagogic Methodology that Promotes Collaboration and Artistic Cross-Pollination

Daithí McMahon, Chris Ribchester, Michael Brown and Mark Randell

Download the PDF of this article

ISSN 2752-3861

Abstract

Contemporary employers are increasingly seeking graduates with strong creativity, communication, leadership and team work skills. Therefore, the curricula and pedagogies of creative higher education (HE) institutions need to ensure they teach these core skills and thus produce graduates that will be competitive in the job market. As students whose education has been disrupted by the pandemic where separation and isolation were enforced, current HE students need to be offered opportunities to reconnect and catch up on lost time socialising and working collaboratively with others. In this context the academics built on previous experience to design a collaborative project that would address this gap and enhance teaching and learning potential.

Rather than teach students in their traditional modular silos, the HE staff involved sought and found synergies amongst their modules which would allow students to work together to produce immersive audio dramas. Together teams of students from the University of Derby School of Arts contributed their input from their area of specialism to create original collaborative works of art. The students represented five different programmes at UG and PG levels with media, performance and music the key disciplines. The findings are based on the observations of the academic staff teaching on the modules and thus employs a form of autoethnography as its methodology.

This paper will contribute to the future development of arts-based curricula in HE whereby interdisciplinary cross-programme project-based approaches are taken on a wider scale. The projects involve using cutting edge audio production technology, Dolby Atmos, making them innovative research pieces and an example of research informed teaching.

Introduction

This paper focuses on exploring the experiences of planning, organising and managing a cross module interdisciplinary arts project. Specifically, the goal was to produce a series of short original audio dramas from idea conception to finished product. The case study was an experimentation to involve five different degree programmes across all levels of undergraduate (Higher Education Levels 4-6) and postgraduate taught (Level 7) study in the University of Derby’s School of Arts. The concept was for students to contribute their own creative subject specialism to a wider project thus inherently create stronger audio pieces. Another aim was to develop vital communication, collaboration and teamwork skills. From previous experience of similar projects the authors found that what are often referred to as ‘soft skills’, require further development amongst higher education (HE) students. This highlights a potential skills gap in the future workforce of the creative industries. The focus on high end podcast drama production has clear sights on increasing the employability of graduates while exposing young minds to the creative possibilities of immersive audio to develop future innovation in the field.

This paper uses theory surrounding teamwork, collaboration and employability to frame the argument that increased opportunities for collaborative work is urgently required in modern HE curricula in the creative arts. The findings are based on the observations of the three key staff members and co-authors of this article (McMahon, Brown and Randell) who were module leaders of the core modules involved and thus led the project. This case study also represents research informed teaching in two ways, first through the development of immersive creative sound productions and second by exploring new teaching and learning approaches that break down barriers between degree programmes that typically have students work in isolated conditions.

Context & Theoretical Framework

Teamwork, Collaboration, and Employability

For most academic disciplines, teamwork is a core component of the HE student learning experience and the ability to work collaboratively with others is a widely identified graduate attribute (Hager and Holland 2006). For example, in the United Kingdom, the Subject Benchmark statement for Communication, Media, Film and Cultural Studies notes that graduates should be able to “communicate effectively in interpersonal settings … [and] … work productively in a group or team, showing abilities at different times to listen, contribute and also to lead effectively (QAA 2019: 12). Later it notes graduates will have “the ability to work across a variety of group and independent modes of study, and within these to demonstrate flexibility, creativity and the capacity for critical self-reflection” (QAA 2019: 16).

The twenty-first century university is pushed to situate itself as a catalyst for economic development, with a mission to bolster regional and national competitiveness (Pugh et al. 2022). Within this context, a focus on teamwork is aligned to employer demands for graduates who can work productively and flexibly with others. Cross-sector surveys of employers consistently highlight the ability to work in a team as a high priority (see National Association of Colleges and Employers 2021; World Economic Forum 2020). This demand is replicated in many of the creative industries, a reflection of work environments that are often collaborative, project-based, and deadline-driven (Higginbotham 2022). In 2018, an Arts Council England sponsored ‘Skills needs assessment for the creative and cultural sector’ highlighted significant gaps related to ‘People skills’, including 45% of employers who noted that their staff need to strengthen their team working skills (CFE Research 2018: 22). Therefore, graduates need to be able to evidence experience of teamworking and the communication, persuasion and influencing skills which underpin this. These skills are valuable on a day-to-day basis, but also when reaching out to others to build networks and contacts. At a larger scale, the ability to work with, and build consensus with others, is seen as essential to enable graduates, and society as a whole, to navigate an increasingly uncertain future (Johnson and Johnson 2014). UNESCO lists “collaborative competency” as one of its eight sustainability competences (Advance HE / QAA 2021).

It is evident then that a concern to emulate the environment of the contemporary graduate workplace has motivated a focus on teamwork activities and collaborative student assignments within the creative disciplines and beyond. The process, impacts, and challenges of facilitating teamwork are widely discussed in the pedagogic literature and is a staple topic in generic HE learning and teaching textbooks (see Marshall, 2019; Race, 2014). Such work highlights the employability-related authenticity of teamwork but stresses its value in other ways. Social constructivist perspectives of learning place a premium on the benefits of interaction and dialogue with others, both students and teachers. This serves to widen perspectives and supports students to construct individual meaning, as they review and filter new ideas and information through their existing schemata (Biggs and Tang, 2011). According to Vygotsky, interactions with others push learners through the Zone of Proximal Development, thereby achieving more than they could by studying in isolation (Vygotsky, 1978). By its very nature, teamwork promotes active learning, widely seen as a key criterion of effective course design for deeper learning (Warren, 2016). Although the significant emphasis placed on working with others in contemporary education is questioned by some (Cain, 2012), repeated evidence suggests that active learning through interaction with others encourages a stronger student performance (Gillies, 2016). The socialisation component of teamwork is also recognised, further encouraging a sense of belonging and identity as a university student with positive implications for engagement and persistence (Krause and Armitage, 2014). This is relevant throughout the undergraduate and postgraduate student journey but especially during the sometimes-challenging transition into university study at undergraduate level (Thomas, 2012; Yorke and Longden, 2008).

The focus in this paper is teamwork, a term deliberately chosen to reflect the nature of exercise that the students were engaged in. However, the related terminology is contested and it is acknowledged that ‘teams’ and ‘teamwork’ are often used interchangeably or simultaneously with ‘groups’ and ‘groupwork’ (Riebe, Girardi and Whitsed, 2017). The authors of this paper agree with Mutch that team working “is seen as a means of harnessing creativity, of responding speedily and flexibly to changing circumstances and of developing synergies to far exceed the sum of individual capabilities” (1998: 51). The intended emphasis is collaboration for mutual benefit around a common goal as students with different skill sets are proactively brought together. For our purposes, the characteristics of teamwork are expanded upon in Table 1, defined in opposition to groupwork. Teamwork is identified as task-focused (in this case, the production of an audio drama), with an emphasis on out-of-class working, with relatively limited tutor intervention. Groupwork can take many forms, including seminars, debates, role-plays, games and crits, with membership sometimes changing frequently within or between teaching sessions, often with significant tutor direction and oversight. However, this binary presentation of teamwork and groupwork is not intended to imply that a clear dividing line is always readily identifiable, and it may often be better to view it as a continuum. Similarly, the tutor skills of facilitating of teamwork and groupwork overlap, as do their opportunities, benefits, and drawbacks.

Table 1: Characteristics of Groupwork and Teamwork

| Groupwork | Teamwork | |

| Rationale | Teaching-focused

|

Task-focused |

| Location | Primarily in-class | Significant out of class component

|

| Membership | Relatively short term, with variable membership

|

Relatively longstanding, with stable membership |

| Tutor Role | Frequent intervention and facilitation | Sets the broad parameters, but emphasis on student independence

|

| Intended Interactions

|

Co-operative

|

Collaborative |

The case for creating collaborative learning opportunities is strong, but “[d]espite many evidence-based approaches for fostering teamwork skills in undergraduate studies, implementation of teamwork pedagogy remains challenging” (Wilson, Ho and Brookes, 2018: 787). These challenges are usually exacerbated when such activities are assessed within a programme, with concerns about the validity and fairness of marking and grades expressed (sometimes very vocally) by both staff and students. The most common concerns focus on the causes and consequences of variable student commitment, resulting in some students benefiting disproportionately from the work of others.

It is not surprising, therefore, that guidance on the implementation of group and teamwork is commonplace. Lane (2008), for example, offers a summary of approaches that tutors can take to maximise the effectiveness of team-based learning and minimise student frustrations. Ensuring there is clarity of goals, purpose and rationale for teamwork is often highlighted. Facilitating an environment of ‘positive interdependence’ (Johnson and Johnson, 1992) is also stressed – the perception that the success of the whole is dependent on all the contributors and that interactions will be mutually beneficial. Creating clear scaffolding for teamwork exercises is important, perhaps with regular ‘check in’ and reporting opportunities especially in the initial university experiences of teamwork. Indeed, gradually building up the scale and challenge of teamwork through a programme of study is a logical strategy. The development of commonly understood and owned ‘ground rules’ around team responsibilities and behaviours is widely advocated. This may well be linked to proactive guidance on, and practice experience of, the interpersonal skills of teamworking. Emerging work around teaching the compassionate micro skills of communication offers some valuable insights in this respect (Harvey et al., 2020). Perspectives vary on whether team membership should be random, student-selected, or socially engineered by tutors. In practice, all probably have a role dependent on the learning context.

Guidance is also wide-ranging on how group and teamwork might be assessed (see McCrea et al., 2016 and Gibbs, 2009). It typically questions an exclusive focus on grading the final outcome, or grading the ‘product’ in such a way that does not account for possible variable contributions from team members. Such weightings might be calculated by tutors drawing on evidence of student engagement with their peers and contributions to the overall task. Self or peer assessment of individual contributions can also be valuable. An even greater focus on grading the ‘process’ of teamwork can be achieved by requiring students to complete reflective narratives articulating key moments and learning from a collaborative assessment exercise. Whatever the approach taken, well-articulated and transparent assessment criteria are essential.

The challenges and strategies outlined above are longstanding, but their scale and importance have been exacerbated by the Covid pandemic, especially during lockdown periods when in-person interactions were minimal and access to practical facilities was significantly curtailed. Whilst the potential for facilitating synchronous and asynchronous connections digitally is significant, the rapid transition to online working and remote teaching proved challenging. The consequences of the pandemic on both the student experience and university research activity are now increasingly documented, helping to highlight its uneven impact demographically and geographically (Arday, 2022). Declining student engagement, disconnection, restricted opportunities for socialisation, and a reduced sense of belonging have been commonly reported, with negative implications for student confidence and mental well-being (Jackson and Blake, 2022; UPP Foundation, 2021). Therefore, the challenges posed by the pandemic set a further key context for the pedagogic approach reported in this paper.

Project Rationale, Outline & Brief

With the ongoing rapid expansion in podcasting (Llinares et al., 2018; Spinelli and Dann, 2019), including the audio fiction podcasts in the US and UK (Watts, 2019), there is increasing demand for arts graduates with creative audio media production skills and experience. However, a combination of recent programme rationalisation in the UK HE sector resulting in fewer Arts programmes, coupled with the drop in demand for radio production degrees, has potentially resulted in a growing skills shortage of specialised creative audio producers. As a result, there are future employment opportunities in this relatively new frontier and projects such as the present case study were initiated in an attempt to address this. In short, the case study had student employability at its core. With this in mind staff sought to create a learning environment and opportunities to simulate the experience of working with other creatives on a shared brief.

The staff at the School of Arts in the University of Derby knew that there were existing synergies between degree programmes, in this case creative audio production, and therefore potential collaborative possibilities across disciplines. As experienced professionals in the different areas of audio media production – audio drama writing, direction and production; music composition and production and sound production and spatialisation – staff leading the three core modules understood and appreciated not only the value but the importance of collaborative work to the success of creative projects. This was partly what motivated the academic staff; offering students the opportunity to get accustomed to team working and how their expertise can contribute to a collective goal.

The staff had previous experience in this pedagogic approach having experimented with a collaborative audio drama project involving students across the University of Derby’s School of Arts (see McMahon et al., 2022). Encouraged by this experience, which highlighted the potential student learning opportunities from collaborative working, the academics set out to expand the possibilities and produce several individual audio dramas. The new approach would offer students more autonomy, agency and creative input. The foundation of the collaboration was a brief for one 15-minute drama to be written and produced by each of the 3rd year BA (Hons) Media Production – Level 6 (BAMeP) students, of which there were six. The BAMeP students were tasked with writing, directing and producing their own productions and thus be the auteurs and leaders of the project. The other degree programmes involved were the BSc (Hons) Music Production – Level 4 (BAMuP) and BA (Hons) Popular Music – Level 4 (BAPoM) who were responsible for writing and producing the musical score and BSc (Hons) Music Production – Level 5 (BScMuP) who were responsible for the sound design and production. This met the learning outcomes of the modules and was aligned with the coursework set by each module leader.

There were two other School of Arts programmes which had some students voluntarily take part. These were the BA (Hons) Theatre Arts (BAThA) who provided the majority of the actors and the MA Film & Screen Production – Scriptwriting pathway (MAFaS) students, two in total, who each provided a script. The MA students would also offer valuable script supervision and mentorship for the less experienced BAMeP writers. In total sixty-one students across the above degree programmes took part.

The brief was fairly simple, rather than work to their own module briefs which would see them create a piece of course work relevant to their discipline, students would instead team up and contribute to a collective project – a 15-minute audio drama. The staff involved identified that this collaborative learning opportunity was possible when they noticed that each of the three core modules involved were timetabled at exactly the same time, 1-4pm on Mondays in the Spring Semester (Feb-May 2022). Therefore, the project was made possible by what amounts to a serendipitous scheduling opportunity. This three-hour slot conveniently offered a structured temporal space where all students would be expected to be in attendance and available to meet with their creative partners and wider team. Furthermore, the BAThA students also happened to be scheduled at this time in the same building and so would be available at that time for auditions and recording. The MA students had class on Monday mornings so were available to participate in the afternoon.

The methodology employed for this project involved direct observation of the students by the three leading academics throughout the semester, with notes of these observations made for later analysis. Since the lecturers were also members of the learning community which they were observing this is classified as autoethnographic approach. The lecturers made observations of students both in class and online on the dedicated Microsoft Teams (MS Teams) channel set up as a shared accessible space for collaboration and communication.

Implementation and Delivery

Shared Sessions

The synchronous scheduling of the three core modules allowed the module leaders to schedule shared sessions where multiple groups could mingle and where shared learning could take place. In between these shared sessions students were taught their core module material in their respective classrooms/labs to prepare them for their contributions to the collaborative projects. This project was taught during the spring semester – a set of 15 teaching weeks running from early February to late May – henceforth referred to as Week 1 through 15.

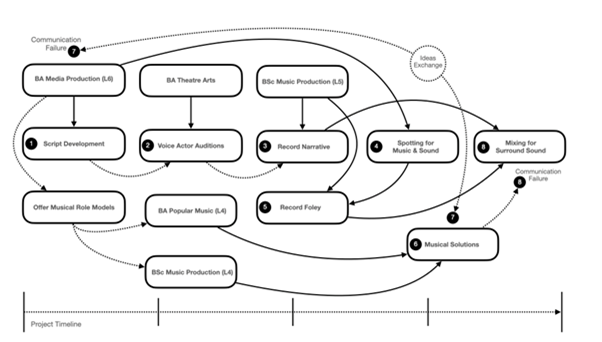

The entire group were scheduled to assemble on at least three weeks, Week 1 for an initial welcome session where staff outlined the brief, discussed expectations around attendance and engagement and allowed students to meet together in person. Another session in Week 4 allowed the BAMeP students as the auteurs to pitch their drama ideas to the wider group. This was a key session because it offered the opportunity for music producers and sound designers to hear the ideas of the writers and get some creative ideas flowing. As part of each pitch there was a Q and A where students could ask for further detail about the projects. There was nearly full attendance in the classroom for the Week 4 pitching session and offered an opportunity for students to meet face to face and interact socially. Week 6 was scheduled to be another collaborative session where the script drafts could be reviewed collectively ahead of recording in the on-site radio and recording studios in Weeks 7 through 10. Week 12 was scheduled as the final collaborative session and was intended to be a critical listening session where advanced drafts of all eight pieces, with soundscapes and music included, would be listened to and appraised by all students. This not only aimed to close the learning loop by allowing reflection on their practice and then feeding this back into practice but also replicates standard industry practice whereby an executive producer listens to an advanced edit and accepts it for dissemination or identifies further edits.

Communication and Online Work Platform

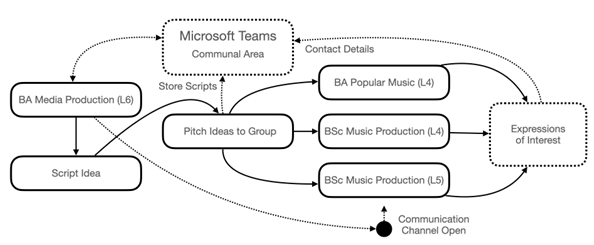

While in-person team working was a key component of the teaching and learning approach, staff recognised that students would need to continue working outside of the set class time. Some of this work would need to occur online as individuals’ schedules would differ and therefore require asynchronous work patterns. To assist the students in collaborating, and to replicate current professional practice, the MS Teams channel was set up with all students from each module attached and afforded full access. Students were advised that this would be the platform used to share creative materials with one another, review drafts, share mock-ups and to facilitate further online dialogue and media production (see Figure 1). Initially this content comprised of pitches by the auteurs in the form of PowerPoint presentations and video recordings of these for those students who missed the pitches and/or wanted to review them. The overall aim was to use the online platform to facilitate engagement outside of class time.

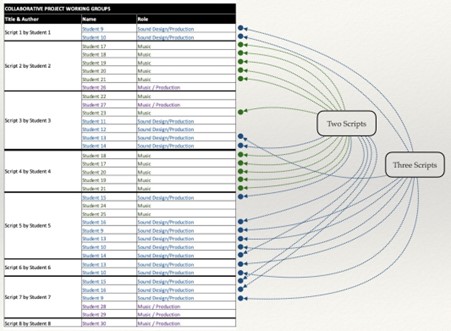

The collaborative project proposal consisted of eight scripts by students identified in this paper as Students 1 to 8. From a historical parable set in ancient Egypt to a supernatural entity terrorising a crew lost at sea, there was a wide variety of projects which offered students opportunities to explore exciting new soundscapes and thematic musical scores. The popularity of some scripts compared to others was somewhat expected but staff wanted groups to form organically rather than students be forced into projects that did not appeal to them.

A Working Groups spreadsheet was set up (see Figure 2) as a live document on OneDrive and linked back to the Teams channel, which registered expressions of interest and included Unimail contact details. Personal email addresses, mobile phone numbers and social media handles were also shared online and in person. This gave students further communication options beyond the University infrastructure in the hope that the increased accessibility and flexibility would improve communication between group members.

Writing, Direction & Production

The studio recording sessions were scheduled for Weeks 7-10. Also known as the production phase, this is always the shortest, most intensive and most expensive phase of media production with pressure on everyone involved to achieve quality performances and audio recordings in the shortest time possible. The circa fifteen-page scripts were recorded in the three-to-four-hour time allotted and students were given appropriate training and support throughout. However, staff made a conscious effort to remain outside studio to allow students space and autonomy to problem solve and complete the task collectively.

The brief for the music students was to produce the play’s main theme music and to produce non-diegetic material to underscore select scenes. The brief for the sound production students was to source and arrange the soundscape involving diegetic audio material and to create any additional Foley sound effects. Additionally, students could engage in innovative practice by spatialising the finished work into a multi-speaker environment – Ambisonic 5.1 and/or Dolby Atmos – to offer an innovative sound experience for the listener and push their learning into new territory. Media projects are constructed over time with layers and complexity added with each contributor’s input and therefore regular communication is paramount. This was explained to students with instructions to be in regular contact with team members both during and between shared sessions. A timeline was offered for the students, carefully mapping out the experience to help manage expectations and interaction. There were some first-year students who opted out of the brief and of the twenty-one potential Level 4 students twelve engaged in the collaborative opportunity.

Reflections on Project Success

All eight projects were completed and delivered in time, however, in class attendance, online interaction and project participation dissipated over the course of the semester. The final Week 12 critique session did not take place as planned and was conducted on a one-to-one basis with students and academics instead.

Communication is a fundamental aspect of media production and project management of any kind and this was an area where weaknesses were observed (see Figure 3). Despite the above issues, there were also many positives. Examples of successful communication occurred between the BAMeP auteurs and BAThA actors in arranging casting and recording sessions. The current generation of undergraduate students are what Prensky (2001) refers to ‘digital natives’ who have grown up with digital media as an everyday part of their lives and are therefore often expected to be very comfortable with digital online communication tools. Overall, this was found not to be the case as will be discussed below.

The in-studio recording sessions were the most successful collaborative sessions where students worked well together to achieve the collective goal of capturing the vocal performances of the actors using professional studios and equipment. Immediate feedback was that these sessions proved intensive and tiring for students but were highly formative and enjoyable experiences. This perhaps has to do with the urgency and importance of these activities and the pressure of limited studio time. A number of actors noted how formative the experience was for them and how they gained valuable content for their voice demo reel. Many of the music students profited from the experience, producing some very interesting demo material that was submitted as a part of their end of module portfolios.

Discussion & Recommendations

The academic staff have learned a great deal from this multi-programme collaborative project experience and these insights will inform their future practice. The findings will also be of interest to colleagues across the sector inspired to facilitate these types of learning opportunities for their students. The academics agreed that perhaps assumptions were made regarding student aptitudes with technology and their confidence with regards socialisation and team-working.

The approach was intended to simulate working conditions and processes in the creative industries, a competitive and often high-pressure environment where creative artists either succeed or flounder. The approach was therefore designed to replicate the challenges of the workplace and what it takes to achieve success.

Some learners will prosper in such an environment, however, educators need to be sensitive to the diversity of the student body, including when working with students at different points in their HE journey, and thus the variety of needs and abilities within the cohort. The authors have identified a number of areas where improvements can be made ahead of future iterations which will improve the learning experience for the students. These are outlined below.

Scaffolding of Teamwork Teaching

The authors learned that students need to be supported to a greater extent in learning what teamwork is and how successful teamwork is achieved. Furthermore, this understanding needs to be developed iteratively over the course of a programme. Part of this will involve getting more comfortable with classmates and encouraging reflection and observation about the roles people gravitate towards. Stepping outside the project and employing a game-based learning approach can break down some of the social issues encountered. Through the use of game-play approaches valuable teamwork principles can be learned and then applied to real-life situations (Trybus, 2015), in this case a professional media production scenario. This approach offers opportunities to develop the vital positive interdependence component of collaborative learning (Johnson and Johnson 1992). The sense of responsibility amongst most members was lost somewhere along the way and this contributed to the challenges faced by some of the groups.

Teamwork works best when all members are working towards a shared goal and feel a sense of pride and belonging in their collective endeavour. For collaborative projects like this to be more successful staff need to build a foundation of teamwork before work on projects can begin. Building game-play into the curriculum would help achieve this but thought needs to be given to the type of games used. To be most effective these should match the patterns of media production along with general games that break down potential barriers and promote socialisation and communication.

When using online platforms and infrastructure to produce creative media, workers need to continuously interact as professionals did throughout the pandemic. The University provided this same infrastructure via MS Teams and students had full access to the software. The MS Teams site hosted collaborative content and was intended to be the ‘sand box’ for work to be shared and edited and for communication to take place. The fact the MS Teams page was lacking in engagement from students points to a potential lack of communication skills and understanding of how to use professional communication media and why it is important. More emphasis should be placed on this aspect of teaching and learning rather than taking it for granted.

Although observed communication and collaboration was limited, the reassuring outcome was that there were some very good finished pieces that met the brief submitted for assessment that involved the work of the three core programmes of students. It seems that more progress was made outside of class and off campus, rather than during the timetabled sessions on campus. This suggests that working in isolation at home was a more comfortable ‘safe place’ for students, despite the attenuation of production results due to inferior technology. Leadership is crucial to a properly functioning team and where leadership was lacking projects invariably struggled. As future producers these skills are imperative and therefore further attention should be given in the curriculum to developing student leadership skills.

Technological Skills

There are differences in how students and staff use digital communication technologies. Students reported that they were more comfortable using the social media platforms What’s App, Instagram and Meta Messenger over the University supported email and MS Teams. Based on the progress made it is clear that interaction did occur via these channels which significantly helped students to plan and organise their projects. However, users are limited in what they can achieve using social media exclusively which is where platforms which have much broader functionality prove their worth.

The lack of use of MS Teams by students can be largely attributed to the lack of familiarity with the software and the academic staff have taken valuable learning from this. The authors challenge Prensky’s assertion that ‘digital natives’ are quick adopters of, and more adept at using, digital technology. Younger cohorts use certain digital communication media, notably social media platforms very well, however they are hesitant with professional work platforms which is a concern given their prevalence in the creative industries. Some of the hesitancy may stem from the difference between the language used colloquially via social media compared to the more formal communication style expected on work platforms.

Scaffolded learning not only in how to use the platform and its various functions – communicating, building project folders, uploading/downloading content, finding content etc – but perhaps more crucially, why a user needs to engage, what their role is in the team, and when they need to act and engage are important. Teachers need to facilitate a better understanding of the media production process and how online communication and collaboration platforms work with the phases of production to collectively achieve the goal of a successful production.

Some students were notably withdrawn from the teamwork activities and preferred to work from home rather than at the University where they have access to specialist equipment, facilities and team mates. The reasons for this are no doubt complex and for deeper exploration by the academy however, some reasoning likely lies in the lasting effects of the pandemic and the enforced lockdowns that had students studying often in very isolated conditions at home or their University accommodation. Indeed, at the time of writing in late 2022, a high proportion of professionals across the creative industries and academia continue to work from home due to the habits established during the pandemic with little or no impact on productivity. Despite these environmental challenges it is the responsibility of academics to prepare students for the future and make up for the lost opportunities to work with others. Academics must dedicate time to the socialisation element of collaborative working because of how fundamental it is to successful professional practice.

Ground Rules & Expectations

Another important element learned was the uneven approach to accountability which was shown. The lack of agreed ground rules, the authors posit, compounded this challenge as this would have outlined clear expectations from each and every member, staff and students. Whatley found that simply agreeing a set of rules does not necessarily guarantee adherence but by reading the rules the students can reflect on their “obligations, expectations of others, and working relationships” (2009: 173). Further research could explore whether rules need to be devised and agreed democratically in order to have a greater chance of success as members are able to take ownership of their roles and responsibilities.

Sensitivity to Levels of Study

Further consideration needs to be given to the different levels of study of the students involved and how expectations from each differ. In an ideal scenario students would be introduced to collaborative learning in Level 4 to gain a grounding of the fundamentals required. With the aim of encouraging students to take creative risks and not be overly motivated by result classification, the grading outcome is pass/fail for all Level 4 modules in the University of Derby School of Arts. In Level 5 the students would refine their skills, take on more responsibly and some leadership. In Levels 6 and 7 students, armed with their previous experiences would be able to take leadership roles and manage projects, delegating tasks to Level 4 and 5 students and ensuring targets are met and the overall goal achieved. Therefore, students would build mastery of their discipline over the years of study and develop leadership and project management skills.

Closing the Feedback Loop

The authors did gather valuable feedback from students via module evaluation surveys that are conducted at the end of each module. Due to ethical considerations these could not be included directly in the current paper however the importance of ‘closing the feedback loop’ is understood and appreciated by the staff involved. By engaging with this process both parties can work towards improving learning which is their common goal (Cook-Sather et al., 2014), this is a continuous process repeated after each instance of collaborative learning so that the teaching and learning approach can be refined and fine-tuned.

This case study highlights the challenges that can arise in a cross programme interdisciplinary collaborative project. Wider engagement with these types of projects, and the study of these as useful pedagogic approaches, is encouraged to develop better teaching and learning strategies. Furthermore, an industry wide survey of UK HE institutions to discover the extent of collaborative team-based instances involving Arts programmes would help inform HE leadership of the extent of group and team work in curricula.

Conclusion

This case study offers an illustration of how challenging it can be for students to fit into a collaborative teamwork project despite access to a suitable learning environment and tools. The environment and skills include access to various skillsets from different disciplines, high-end technical facilities, supervisory expertise and synchronous timetabling.

The teaching staff observed apparent weaknesses in the so called ‘soft skills’ of communication and collaboration which this paper argues are in fact very much vital skills for success in the creative industries. It is important HE students learn more than just technical skills, artistic experimentation and creative expression. The authors argue for the inclusion of collaborative opportunities as a core element in undergraduate creative arts programmes and the use of game-play that replicate the patterns of media production while helping breakdown communication barriers. This will help students develop their own specialism and confidence and result in superior, potentially award winning, finished products. Students will also learn from one another and improve their own skills in disciplines adjacent to theirs. The most valuable benefit would be the improved employability of the graduates due to their formative training as team players and collaborative creatives capable of working off their own initiative while contributing to a collective media product.

There are marked differences in how younger generations (most HE students) and older generations (most HE academics) use digital communication technologies. There is an important lesson learnt here in that although technology can facilitate and sometimes enhance our communicative abilities, communication tools are just that, tools, and still require a worker to operate them and to use them properly to complete a job. Furthermore, like any tool appropriate training and practice is required to use it safely, appropriately and effectively – a tool is only useful in the hands of a skilled craftsperson. Communication training should be incorporated into the curriculum including not only the effective use of technology but the wider reasons the tools exist and the importance of maintaining open channels of communication. These include keeping teammates up to date on progress, changes, individual responsibilities, deadlines, problems encountered and so on. Effective teamwork requires strong leadership and this was not always present in the current case study thus the development of leadership skills is also necessary within the creative curriculum.

About the authors

Daithí McMahon, PhD, is Assistant Head of Discipline for Music & Performing Arts and Senior Lecturer in Media at the University of Derby where he teaches scriptwriting and media production across UG and PG programmes. He is a critically acclaimed and multi-award-winning radio playwright, director, audio producer and sound artist. His research interests include the convergence of radio with digital media, the political economy of media industries and the media consumption habits of contemporary audiences. He is currently working on a number of research focused podcasts and has recently expanded his practice-based research to include screen production including the documentary film, Our Story (2020), charting the experiences of the Irish diaspora in Derby, a health education music video for the learning-disabled, Poo Busters (2021), and a collaborative short film co-production involving the visually impaired community. His pedagogic research is focused on the development of HE curricula and enhancing student learning through live, collaborative, inter-disciplinary practice-based art and design projects that engage with the wider business, arts and civic communities to provide collective benefits.

Chris Ribchester is an Associate Professor: Learning and Teaching with a cross-university enhancement and pedagogic research remit. He has a longstanding interest in the processes of learning, teaching and assessment and this is reflected in his research activities and publications. Chris has led and collaborated with others on multiple projects exploring different dimensions of the student and staff experience, focusing on both discipline-specific pedagogies (e.g. geography fieldwork) and more generic topics (e.g. assessment feedback, the transition to university, and the teaching of ethics).

Michael Brown, MA, BSc, PGCE, AmusLCM, FHEA, is the Programme Leader for MA Music Production at the University of Derby. After graduating in 1990 with a BSc (Hons) Degree in Software Engineering, Mathematics and Music (Derby), he joined the University of Derby Academic Team to deliver classes in Music Technology, Composition and Performance, teaching predominantly upon the undergraduate popular music provision. In 2000, he gained a Master’s degree in Contemporary Composition (Salford) and a PGCE (Trent University) and began developing numerous new modules in composition and performance, teaching at both undergraduate and postgraduate levels. In 2012, he was honoured with the university Programme Leader of the Year award for his efforts. He is also an active artist, composer and musician with experience in working with artists nationally and for local television providing a variety of multi-media solutions. He holds diplomas in both Art and Music, which combine to serve his research interests in computer creativity within the arts; he has presented and published his research in multimodal creativity internationally.

Mark Randell, MA, BA (Hons), Cert-Ed (PCE), MIScT (Reg) FHEA, is a Technical Instructor Audio Media, Associate Lecturer, University of Derby. Initially working in FE and completing an HND in music then PCE (Cert-ED), he joined the University of Derby in 2010 as part of the technical team. While working he graduated with a BA (Hons) in Popular Music with Music Technology then recently completing an MA in Music Production. Within his role he supports multiple activities relating to music and audio production across a wide range of disciplines. Concurrently he has been involved with teaching technical and practical activities. Mark has worked within the music and audio production industry for almost 20 years. His research interests are in the field of audio-visual perception and multi-channel sound.

References

Advance HE / QAA. (2021) Education for sustainable development guidance. York / Gloucester: Advance HE / QAA.

Arday, J. (2022) ‘Covid-19 and higher education: The times they are a’ changin’, Educational Review, 74 (3), pp. 365-377.

Biggs, J. and Tang, C. (2011) Teaching for quality learning at university. 4th edn. London: Open University Press.

Cain, S. (2012) Quiet: The power of introverts in a world that can’t stop talking. London: Penguin Books.

CFE Research. (2018) Skills needs assessment for the creative and cultural sector: A current and future outlook. Leicester: CFE Research.

Cook-Sather, A., Bovill, C. & Felten, P. (2014) Engaging students as partners in learning and teaching: a guide for faculty. Hoboken: Wiley.

Gibbs, G. (2009) The assessment of group work: lessons from the literature. Oxford: ASKe.

Gillies, R. M. (2016) ‘Cooperative learning: Review of research and practice’, Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 41 (3).

Hager, P and Holland, S. (eds) (2006) Graduate attributes, learning and employability. Dordrecht: Springer.

Harvey, C., Maratos, F.A., Montague, J., Gale, M., Clarke, K. and Gilbert, T. (2020) ‘Embedding compassionate micro skills of communication in higher education: implementation with psychology undergraduates’, Psychology of Education Review, 44 (2), pp. 68-72.

Higginbotham, D. (2022) How to get a creative job. Available at: https://www.prospects.ac.uk/jobs-and-work-experience/job-sectors/creative-arts-and-design/how-to-get-a-creative-job (Accessed: 10 June 2022).

Jackson, A. and Blake, S. (2022) Building students’ sense of belonging needs time and energy. Available at: https://wonkhe.com/blogs/staff-perceptions-of-belonging-and-inclusion-in-higher-education/ (Accessed: 29 June 2022).

Johnson, D. and Johnson, R. (1992) Positive interdependence: The heart of co-operative learning. Edina, MN: Interaction Book Company.

Johnson, D. and Johnson, R. (2014) ‘Cooperative learning in 21st century’, Anales De Psicologia, 30 (3), pp. 841-851.

Krause, K-L. and Armitage, L. (2014) Australian student engagement, belonging, retention and success: a synthesis of the literature. York: HEA.

Lane, D. (2008) ‘Teaching skills for facilitating team-based learning’, New Directions for Teaching and Learning. 116, pp. 55-68.

Llinares, D., Fox, N. & Berry, R. (2018) Podcasting: New Aural Cultures and Digital Media. Cham: Palgrave Macmillain.

Marshall, S. (ed) (2019) A Handbook for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education: Enhancing Academic Practice. 5th edn. London: Routledge.

McCrea, R., Neville, I., Rickard, D., Walsh, C., and Williams, D. (2016) Facilitating group work: a guide to good practice. Dublin: Technological University Dublin.

Mutch A. (1998) ‘Employability or learning? Groupwork in higher education’, Education and Training, 40 (2), pp. 50-56.

National Association of Colleges and Employers. (2021) Job Outlook 2022.

Prensky, M. (2001) “Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 1”, On the Horizon, Vol. 9 Issue: 5,pp. 1-6, doi: 10.1108/10748120110424816

Pugh, R., Hamilton, E., Soetanto, D., Jack, S., Gibbons, A. and Ronan, N. (2022) ‘Nuancing the roles of entrepreneurial universities in regional economic development’, Studies in Higher Education, 47 (5), pp. 964-972.

QAA. (2019) Subject Benchmark Statement: Communication, Media, Film and Cultural Studies. Gloucester: QAA.

Race, P. (2014) Making learning happen: A guide for post-compulsory education. 3rd edn. London: Sage.

Riebe, L., Girardi, A. and Whitsed, C. (2017) ‘Teaching teamwork in Australian university business disciplines: Evidence from a systematic literature review’, Issues in Educational Research, 27 (1), pp. 134-150.

Spinelli, M. & Dann, L. (2019) Podcasting: The Audio Media Revolution. London: Bloomsbury.

Thomas, L. (2012) ‘What works? Facilitating an effective transition into higher education’, Widening Participation and Lifelong Learning, 14, pp. 4–24.

Trybus, J. (2015). Game-Based Learning: What It Is, Why It Works, and Where It’s Going. Miami: New Media Institute. Available at: http://www.newmedia.org/game-based-learning–what-it-is-why-it-works-and-where-its-going.html (Accessed: 3 Sept 2022)

UPP Foundation. (2021) Turbocharging the future. London: UPP Foundation.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978) Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Warren, D. (2016) ‘Course and learning design and evaluation’, in: H. Pokorny and D. Warren (eds) Enhancing Teaching Practice in Higher Education. London: Sage, pp. 11-46.

Wilson, L., Ho, S. and Brookes, R. (2018) ‘Student perceptions of teamwork within assessment tasks in undergraduate science degrees’, Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43 (5), pp. 786-799.

World Economic Forum. (2020) The Future of Jobs Report 2020. Geneva: World Economic Forum.

Yorke, M. and Longden, B. (2008) The first-year experience of higher education in the UK: Final Report. York: HEA.

Watts, E. (2019) “Drama Podcasts An overview of the US and UK drama podcast market” BBC Commissioned Report. London: BBC.

Whatley, J. (2009). Ground Rules in Team Projects: Findings from a Prototype System to Support Students. JITE. 8. 161-176. 10.28945/165.