What We Need to Be Here: Pedagogical Practices of Access and Prioritising People

Jo O’Brien and Sunny Nestler

Email: josephobrien@ecuad.ca; snestler@ecuad.ca

We want to begin this text with a question:

Is now a good time for this paper?

Because, if it isn’t, and if you put this paper down and go do something that you need to do–

to stretch,

to eat,

to rest,

to play,

to give support,

to be elsewhere,

to do something else,

or to do nothing at all–

If you stop now and walk away, then you’ve gotten

to the point of this article much more quickly than if

you stay here, push onwards, and read through.

But, if now is a good time – or if it’s not a good

time, but it is what you have – then welcome,

and thank you for spending your time here.

Introduction

This paper introduces, contextualises, and shares the process of What We Need to Be Here – a practice that we often use to begin conversations about access. WWNTBH is an ongoing and evolving socially engaged artwork, workshop, and community practice. We developed WWNTBH in different forms and contexts over the past decade to honour relationships and needs. It has taken place with groups of students, colleagues, and peers across synchronous and asynchronous modalities, and both in-person and online. We have used WWNTBH in university classrooms and community organisations, and as an informal and sustaining practice of care between friends.

Our hope here is that those unfamiliar with the slow work of access might feel welcome and supported in trying new ways of working, and that all of us might join in learning together. The first section of this paper traces our individual relationships to access, the university, and communities of mutual support. The second section details our processes for WWNTBH and shares our rationale for those processes. To help situate WWNTBH in fuller context, the last section draws on critical discourse, past workshop outcomes, and our broader practices of access-oriented pedagogy.

What do we bring?

WWNTBH is one of the most frequent ways we start off a new term with students. We tend to work with small classes (18-30 students) of university students from across a range of art and design degree programs each year. Regardless of whether we are teaching studio art, writing-intensive, or theory-focused courses, we approach each course we teach from a place of centring access. WWNTBH affirms our commitment to access, to our students, and to ourselves from the very first time we gather. Although we each learned about centring access through community organisations, we understand incorporating access within the university to be an essential and liberatory practice for ourselves and those we work with.

Nestler’s understanding of accessible spaces comes from over a decade of experience in consensus-based worker collectives at community bike shops. These spaces practise anti-oppressive ways of facilitating mechanical skill sharing and bicycle recycling. Each shop’s way of working responds to the needs and gifts of those in the neighbourhoods they serve. O’Brien’s understanding of access is shaped through their experience of mutual-support networks that practise access and reciprocity without ever naming them as such. These networks prioritise support, have low-barrier memberships with no dues or fees, and allow members to keep coming back as needs and abilities change over time.

Nestler’s experience with more formal and intentional access practices includes tools such as consensus-based decision making, conflict resolution, de-escalation, and group agreements. They approach group dynamics as a set of malleable and constantly shifting relationships that – like any other relationship – require effort and intention to maintain. They understand the process of identifying and addressing access needs as one part of that relational maintenance work.[1] O’Brien draws on their embodied and tacit knowledge of access practices and works to find language to articulate these practices as part of their pedagogy. They understand centring access as a way to shift from access being understood as an individualised “problem” to being a collective project that is fundamentally necessary and potentially joyful (Day, et al., 2021).

In the practices we discuss in this paper we both draw on lessons and strategies learned in community spaces and from dedicated organizers. We both understand that in doing so we are continuing a long tradition of using community-focused practices to inform our pedagogical practices – practices which are then often seen as radical or transgressive within the university context. We work this way because academia is often a stale and broadly conservative place and moving it towards other possible futures requires the help of liberatory practices from beyond the university. Current conversations around ungrading, labour based grading, and other alternative modes of marking often reference the influence of broader abolitionist or anti-carceral justice movements (Inoue, 2019). Similarly, our efforts to foreground and prioritise access and support in our pedagogical work draws on the work that activist and community groups have done to imagine mutual aid networks outside of institutions (INCITE!, 2007). What we bring here is not new knowledge, but the application of what we have learned in community and movement spaces that are freer and more attuned to the needs of those who make them.

How do we bring what we bring?

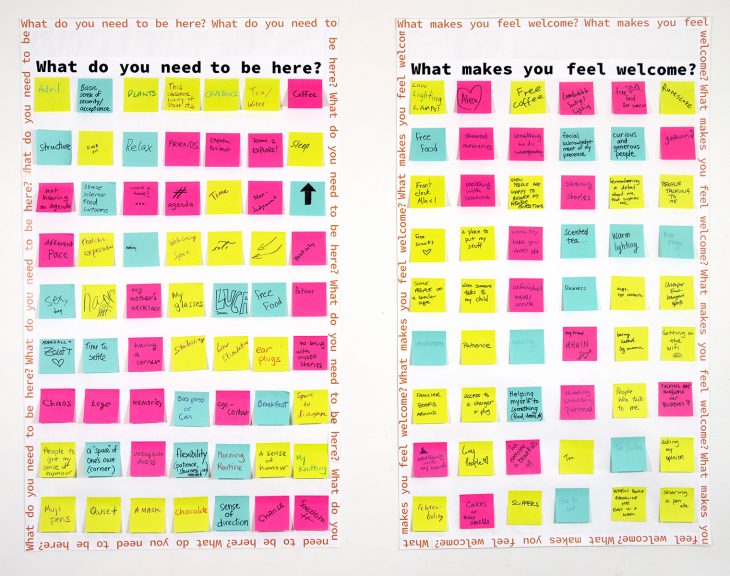

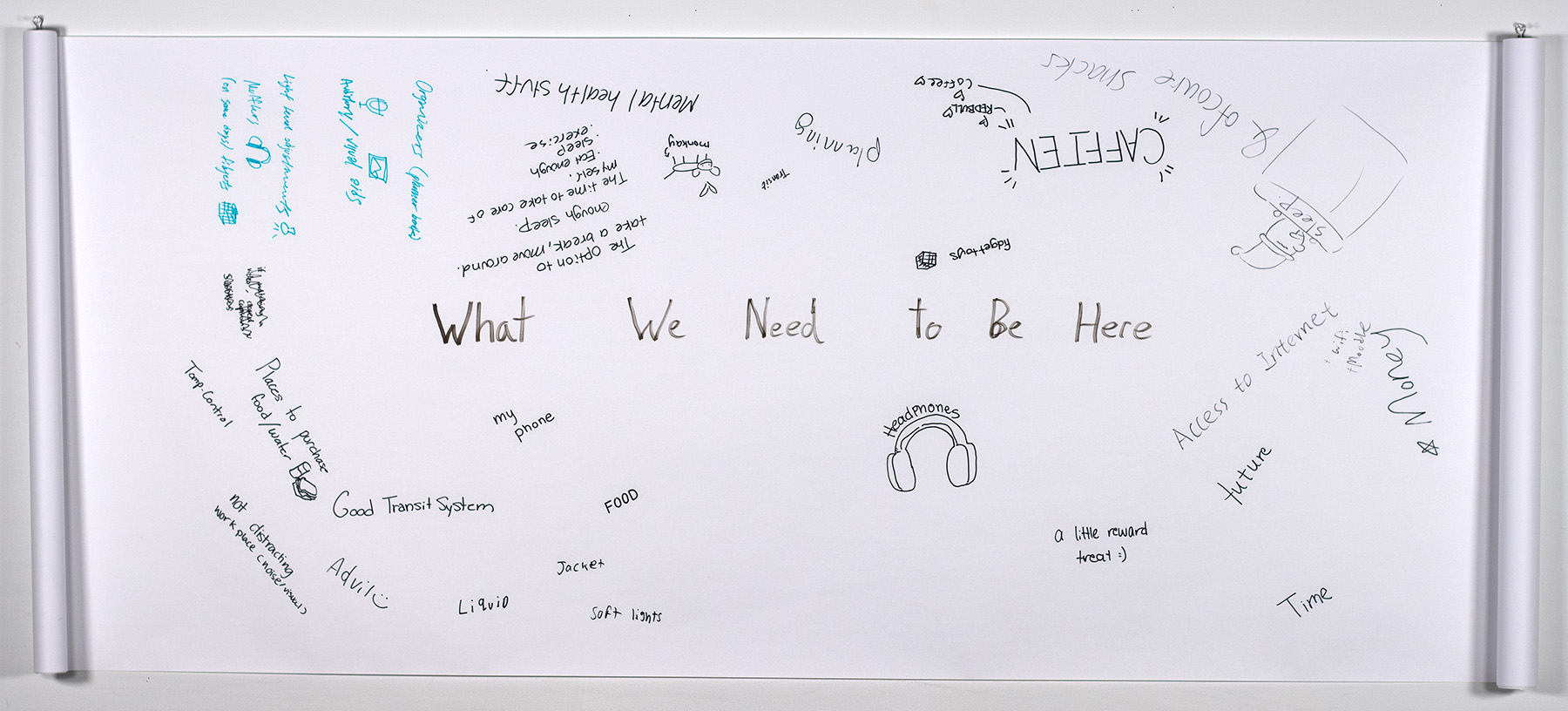

Whenever we come together, we need to introduce the framework for the gathering, and acknowledge that our diverse backgrounds provide us with disparate ways of being in community. In this sense, WWNTBH becomes a first step. Hoang (2017) notes that “community requires that identity and culture become shared processes,” with this in mind we offer a question: what do we need to be here? This question becomes our first gesture as facilitators, we ask this to the group and provide time to think, write, and share (Figure 1).

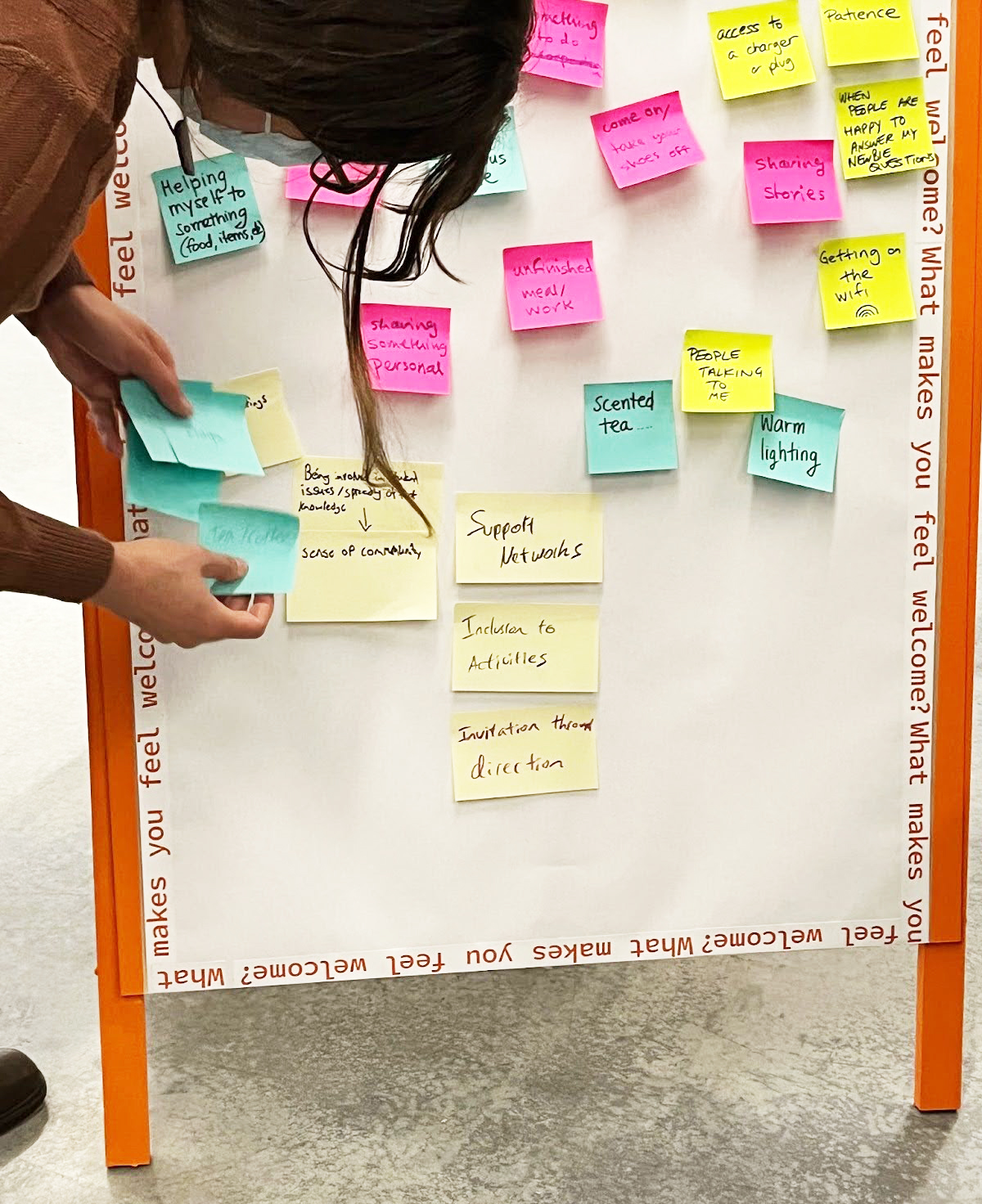

We then continue with a second question. Nestler often asks: “what do we bring to the group?”, which can be a personality trait, physical object, knowledge, skill set, dream, or desire (Figure 2). Taking a slightly different approach, O’Brien often uses “what makes you feel welcome?”, which might be an action, environment, relationship, object, or habit (Figure 3). In all cases, these second questions offer bridges to conversations about how we want to come together – treating this decision as collective, rather than pre-established. Sometimes the group shares aloud what they need or bring. Other times the groups write their responses and create a physical or digital word cloud, which is then discussed. The discussions that result from these initial questions is where the work of addressing access begins (Figure 4).

We ask our students what they need to show up in the classroom because we want to know: how are their unique experiences and challenges showing up in their current, ephemeral selves? Viewed side by side, we can assess the needs of the group against what the group brings, start to have conversations about areas for potential harmony or conflict, and externalise a shared visualisation of what we have in the room (Figure 3).

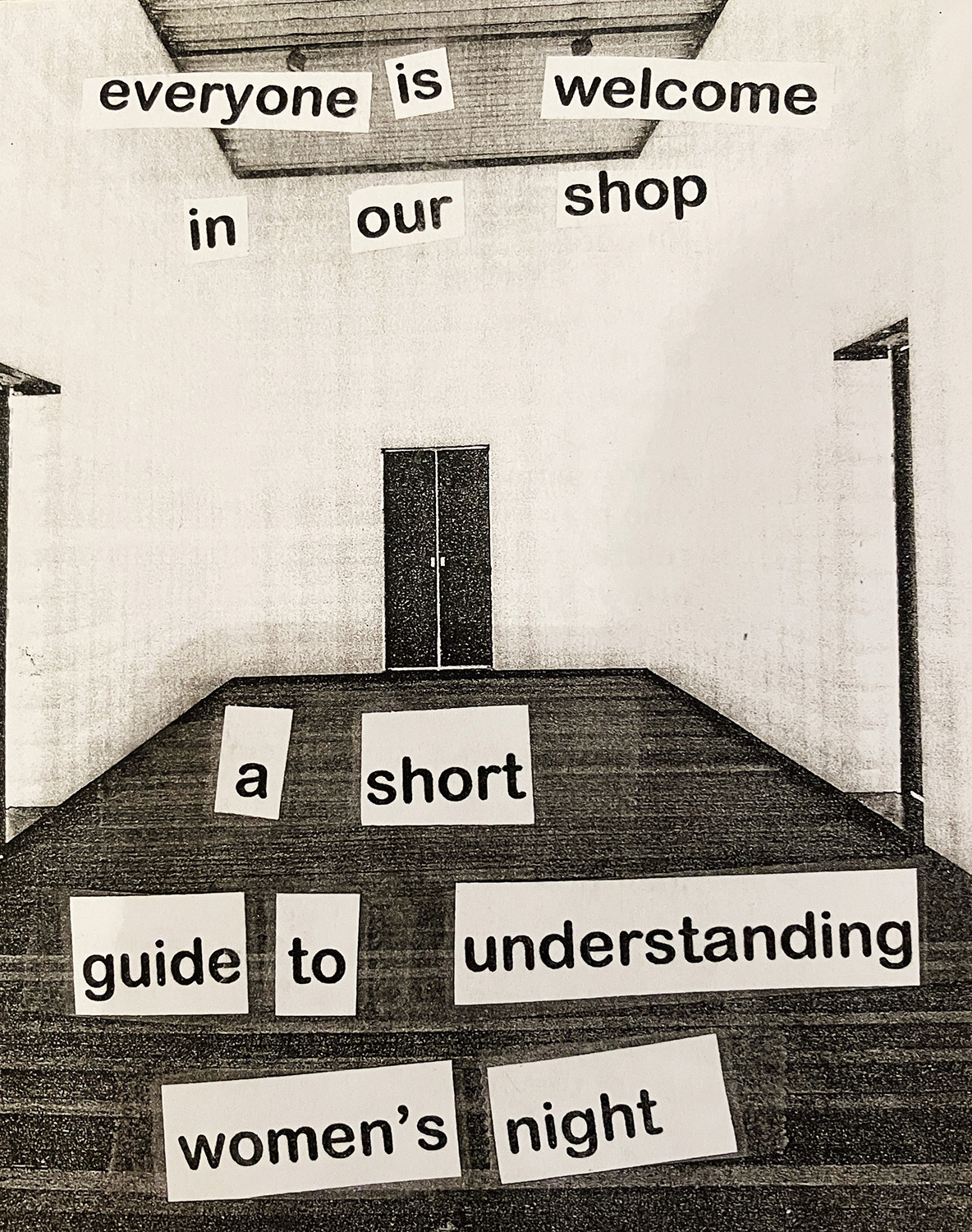

More able-bodied and neurotypical people have more of their access needs met by the existing access infrastructure. This is true no matter how we delineate the boundaries of the space, but we should still take care to co-create those boundaries – is the space online, in-person, or a hybrid of the two? Is the group large or small, synchronous or asynchronous? Is this space meant to address a particular need? In Nestler’s past work in community bike shops, Gender Liberation spaces were created to foster access for people for whom gender was a barrier to accessing the shop (Figure 5). Identifying access needs in a space allows us to measure whether the space is meeting those needs. If it is not, then addressing a particular need or set of needs may be required to generate momentum towards inclusion (Nestler, ca. 2007/8). WWNTBH is a tool that can begin building a foundation for this process of access.

Our needs and our bodies are our own, but every event, place, and relationship is a negotiation of needs among everyone who gathers. Access needs are not binary. When our access needs are not met, it does not always mean we cannot show up, sometimes it means that we show up with varying degrees of presence, or that it takes disproportionate amounts of energy to show up at all. What would it be like if we were able to reorient ways of being, working, and coming together so that people and our varied needs and skills were always the starting point? What if the first question of any gathering was about what we each need to be able to show up?

Why do we bring what we bring?

Understanding that every student has a valuable contribution to offer to a learning community means that we honor all capabilities, not solely the ability to speak.

bell hooks, Teaching Critical Thinking (2010), p. 22

WWNTBH is one of many different activities that we both use as part of our respective pedagogical practices. It is not meant as a one-off activity where we discover our students’ needs, address them, and then create an ‘accessible’ class. Instead, it is one step in challenging and dismantling the expectations and assumptions carried by everyone who enters a classroom. We each practise access-oriented pedagogy according to our strengths, experiences, and expertise, but there are a few guiding principles that we share:

- Access is not a new form of accommodation; it is an alternative to an accommodation model.

- Access depends on agency and cannot exist without it.

- Access, done well, is slow work.

Access-oriented pedagogy requires understanding that access needs are ways of framing and negotiating difference that is distinct from an “accommodation” model (Behrgs, et al., 2016). Accommodation models of accessibility seek to address barriers to access after the fact – when accessibility is retroactively applied those who need accommodations are burdened with securing them. Accommodation models rely on pre-established thresholds and policies to function, and universities almost always use the restrictive medical model (Ho, 2020).[2] Contrastingly, access-oriented pedagogy draws on Carmen Papalia’s (2020) concept of Open Access. Open Access accepts that we each hold the best knowledge of our own access needs, and that this knowledge is the basis from which we should approach access (Ibid). With access-oriented pedagogy we treat access needs and difference as inherent. In turn, students become more comfortable expressing their own needs and attuning to the needs of others. As two students put it:

“I think the way you normalise accommodation provides such a safe space to allow for more meaningful learning. If someone needs an extension they are not made to feel like it’s a terrible thing to ask for. I also enjoyed the way we were allowed to show up and be in the space to whatever capacity we could.”

And:

“I felt like most of my peers were very kind and considerate of the space they were taking up, and held space for others when needed.”

One of the biggest hurdles to implementing access-oriented pedagogy is that many students are taught to expect a lack of agency around their access needs. A key element of access-oriented pedagogy is supporting students in reclaiming this agency. Access-oriented pedagogy aims to negotiate the tangled, complex and often conflicting webs of needs that arise, while also inviting articulations of what is not needed or what is off limits. Felicia Rose Chavez (2021) and Annie Canto (2020) both note that for racialised and other marginalised students being able to set boundaries around what conversations are off limits –and having those boundaries respected– is often an essential need. Supporting student agency supports a richer learning experience. One former student sums this up, saying:

“I think a large part of [being able to show up fully] is the way you preface things, you give us agency over our own participation by saying we can do as little or as much as we feel comfortable with. Acknowledging that everyone operates on different levels of capability without being penalised creates a great space of learning and engagement.”

And, as another student noted, agency also reduces stress:

“Yes, I could bring as much of myself as I wanted to class because I felt like I didn’t need to worry that I’d have to bring parts of myself to class that I didn’t want to.”

Access-oriented pedagogy is our dreaming and striving towards other possible ways of working within the university. It is a call to collaborators and co-conspirators who want, or need, a university that is unrecognisable from its current form. Access is about relational forms that prioritise people over preconceived notions of how things will run, or desires for efficiency. Beginning from access needs is slow work. Access requires building relationships, it depends on trust earned and shared over time, and it means accepting that this is fundamentally inefficient work (Figure 6).

Epilogue

While writing this paper, our access needs changed many times, including right before the deadline when I (Nestler) experienced the onset of a chronic illness affecting the vision in my left eye. The academic deadline being what it is, we found ourselves in the position that many students know well –nervously requesting an extension– while I worked through the processes of going on medical leave, requesting accommodations from my university workplace, and making hard decisions about how and when to type blurry words against a dimly lit screen.[3] Our bodies will always find a way to remind us that WWNTBH is practice-based rather than theoretical, and that unlearning the pressures of productivity is as vital for ourselves as it is for our students.

[1] An access need is something that someone requires to be fully present in a space. Access needs are universal in that everyone has them, but specific in that everyone’s’ are different (Luk, 2016).

[2] The medical model of disability treats healthcare providers as disability ‘experts’ who can diagnose disability and prescribe accommodation. The medical model is relatively standardised, efficient, and has very little room for the lived experience and knowledge of the disabled person (Olkin, 2022)

[3] We extend our thanks to the editors of this issue, who quickly granted our request without question or pause – and who also explicitly invited requests for extension (this is what access looks like!).

About the authors

Jo O’Brien (they/them) is an artist, educator, and researcher whose work explores the queer-crip potential of confusion as both a politicised form of resistance and a call for collaboration. Their practice includes material and social forms of art-making, practice-based and traditional research, and access-oriented pedagogy and community building in the University context. Jo’s work is often collaborative, and their pedagogical research has been supported through fellowships and grants. Currently, they are a doctoral candidate in artistic research at the University of Applied Arts Vienna, where they examine the relationship between legibility and illegibility, confusion, and community through lens-based media, text, and somatic practices. They are also a Lecturer in the Faculty of Culture and Community at Emily Carr University of Art + Design.

Sunny Nestler is an interdisciplinary artist and community activist who also has a background in science. Their work is rooted in drawing and painting, and expands into animation, illustration, writing, bookmaking, 3D modelling, and virtual reality. Their practice has been supported by Canada Council and BC Arts Council grants, and residencies at the Banff Centre. Sunny has been active in a number of community-based organisations, such as the Bike Kitchen at University of British Columbia, as a board member and board chair at Unit Pitt Gallery, and leading out on the grant-funded project VR Club, which aims to democratise access to new media. Sunny lives on unceded Coast Salish territories belonging to the xwməθkwəy̓əm (Musqueam), Skwxwú7mesh (Squamish), and səlilwətaʔɬ/Selilwitulh (Tsleil-Waututh) First Nations, and is an Assistant Professor in the Faculty of Culture and Community at Emily Carr University of Art and Design.

Works cited

Behrgs, M., Atkin, K., Graham, H., Hatton, C., and Thomas, C. (2016) ‘Implications for public health research of models and theories of disability: a scoping study and evidence synthesis’, Public Health Research, 4(8), pp. 1-166. Available at https://doi.org/10.3310/phr04080 ((Accessed 31.03.24).

Canto, A. (2020) Praise for Discord: Collaborations in Talking Back. M.F.A. Thesis. Emily Carr University of Art + Design. Available at: https://arcabc.ca/islandora/object/ecuad%3A15680/datastream/PDF/view (Accessed 31.03.24).

Chaves, F. (2021) The Anti-Racist Writing Workshop: How to Decolonize the Creative Classroom. Chicago: Haymarket.

Day, J., Hughes, S., Zanders, C., Zanen, K.V., and Mooz, A. (2021) ‘What Does a Good Teacher Do Now? Crafting Communities of Care’, Pedagogy, 21(3), pp. 389-402.

Ho, A.B.T., Kerschbaum, S.L., Sanchez, R., Yergeau, M. (2020) ‘Cripping Neutrality: Student Resistance, Pedagogical Audiences, and Teachers’ Accommodations’, Pedagogy, 20(1), pp. 127-139.

Hoang, T. (2017) This is What Community Looks Like, Zine, no. 1, Pomona: Mutedtalks & Los Angeles Zine Fest.

hooks, b. (2010) Teaching Critical Thinking: Practical Wisdom. New York: Routledge.

INCITE!. (eds.) (2007). The Revolution Will Not Be Funded: Beyond the Non-Profit Industrial Complex. Durham: Duke University Press.

Inoue, Asao. (2019). Labor-Based Grading Contracts: Building Equity and Inclusion in the Compassionate Writing Classroom. Denver: University Press of Colorado.

Luk, L. (2016) ‘Our Community Bikes: Anti-Oppression Workshop’ [Workshop], PeerNetBC. Our Community Bikes. 28 February.

Nestler, S. (ca. 2007/8) Everyone is Welcome in Our Shop, Zine, no. 0, Vancouver: Megaspora Press.

Olkin, R. (2022) Conceptualizing disability: Three models of disability. Available at: https://www.apa.org/ed/precollege/psychology-teacher-network/introductory-psychology/disability-models (Accessed 31.01.24).

Papalia, C. (2020) ‘For a New Accessibility’, in A. Wexler and J. K. Derby (.ed) Contemporary Art and Disability Studies. New York: Routledge, pp. 59-75.