Recycle Archaeology: Community Reuse of Archaeological Disposals

Marley Treloar

Email: treloarm@uni.coventry.ac.uk

Download the PDF of this article

ISSN 2752-3861

Abstract

In this paper, I interview Dr Helen Wickstead, director of Recycle Archaeology about the reuse of usually discarded archaeological materials as an alternative to disposal. I explain through recent pilot projects partnered with Recycle Archaeology, how archaeological materials can be used by students, researchers, artists and the public to create new community-focused programmes, which put heritage in the hands of the public. These pilot projects engage partners in community curating, creative transformations and digital development through the recycling of de-selected finds. Expanding from the public reuse, this paper begins to unpick how partnering with organisations like Recycle Archaeology can inform how Gallery, Library, Archive, Museum (GLAM) organisations can engage their audiences and communities in new innovative ways otherwise unavailable to organisations within the cultural sector. This is one case study from a larger body of research, which interrogates the new development of hybrid digital and physical participation between communities, publics and cultural organisations. I explore how GLAM organisations can better utilize their current staff’s capabilities towards more inclusive community participation, assessing the appropriate digital tools and balance of hybridity which promotes the most sustainable programming for communities in physical and digital spaces.

Introduction

With the impact of Covid-19 on the cultural sector, having closed buildings, halted organisational programming, needing to adapt to online engagement strategies and organisations reorganising after a wide range of redundances (Museums Association, 2021), digital tools, spaces and programming are more essential than ever. Recent reports indicate that 40% of audiences want to experience culture both online and in-person, with one in three interested in participatory programming (Audience Agency, 2021), but evidence of digital participation has yet to facilitate this level of audience engagement. One of the access barriers is the organisation’s ability to harness its digital spaces towards programming for hybrid digital and physical participation in line with audience expectations post-Covid-19 (digitally accessible exhibitions, recorded events, online programming). The digital capability issues cultural organisations face includes adapting existing programming into new digital or hybrid formats, staff confidence using digital tools, increased demands on organisational workload, staff loss due to the pandemic and increased accessibility and diversity demands from funding bodies and the public regarding cultural programmes. Addressing a call for participatory design thinking (Mason and Vavoula, 2018), my research responds to how cultural organisations can better work together with community partners to meet their individual and collaborative needs, while presenting alternative ways of working to disrupt established Gallery, Library, Archive, Museum (GLAM) power structures and barriers to access. My research extends Mason and Vavoula’s framework from participatory design thinking within GLAM organisations to include external community partners through practice, and how these local, non-museum authority voices can become embedded to make space for inclusive and diverse perspectives within the cultural sector. This case study with Recycle Archaeology sets a foundation in my research for community development, participatory practices and the development of sustainable programming frameworks inclusive of digital tools for partner organisations. Identifying organisational, community and digital needs, this case study begins to unpick ways digital and physical material can develop values and expand space for knowledge creation, building off existing digital museology studies (e.g., Geismar, 2018) and dialogue surrounding participation in the digital sphere (Jenkins. Ito, boyd, 2016). The two co-creative projects in this paper explore recycling archaeological finds into student-developed handling collections as well as creative reuse through the development of public artworks.

Recycle Archaeology

What are de-selected materials and why should we recycle them? Throughout this paper, I will be discussing two pilot projects which took place between September 2021 and March 2022 with the archaeological reuse initiative Recycle Archaeology and partner cultural organisation Kingston Museum. Recycle Archaeology, led by Chartered Institute for Archaeologists (CIfA) member Dr Helen Wickstead (HW), aims to recycle and find alternative uses for de-selected archaeological finds which cannot find homes in museums, which would otherwise go to landfill in community-led programmes. These projects seek to provide alternative options to reburial or disposal, engaging members of the public, makers, artists and community spaces such as schools or local community centres. I sat down with Dr Wickstead to discuss the beginnings of Recycle Archaeology, the archaeological archives crisis and how Recycle Archaeology hopes to shift perspectives on the disposal of archaeological material (Figure 1).

MT: How did the idea for Recycle Archaeology come about?

HW: OK, so there’s a long answer and a short answer. The long answer is, it comes about through my experience of working in archaeology, both as a commercial archaeologist, as a researcher, and running community archaeology excavations. There is a big difference for me between the vast majority of archaeological excavation, which is essentially part of the construction industry and is paid for by developers. That has a whole different rationale and kind of way of being compared to community archaeology, where you have all these other benefits to doing excavations, to do with how people get on with each other and how they feel, and all those sorts of kind of things. I’ve felt for a long time that the vast majority of archaeology that we do in this country is driven very much by the corporate agenda of large developers, and effectively is counterproductive to what archaeology should be about, which is to do with connecting people to their past, which belongs to everyone. That’s the long answer.

The short answer is that in 2019 the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists started a new initiative which was born out of what’s called the Archaeological Archives crisis. That crisis is the fact that all over the country in archaeological units and portacabins and various sort of sheds, the artefacts that come out of the ground, and the ecofacts as well, are mounting up in boxes. There are 9000 undeposited archaeological archives. Most of those are excavation projects that can’t find a home in museums as a result. So, we’ve got a large volume of material which really should belong to the public but actually can’t be shared with them. Developers don’t pay for that to happen. So CIfA in response to that said, well, what will we do? We’ll try to collect less stuff. They produced a series of workshops where they got all the finds specialists together and said “OK, now you guys you need to throw out more things”, basically. They said, “you need to, when you’re looking at things, you need to make a policy for what you will retain, and a policy for what you’ll discard, and you need to be explicit and upfront about that”, so all quite good things. Archaeologists haven’t always been able to keep everything, and there’s always been these sorts of policies. But it seemed to me that the range of options for that material is quite restricted. The examples that the Chartered Institute for Archaeologists was putting forward were limited to landfill for the finds specialists or leaving things on site. That seemed like a wasted opportunity for somebody who thinks that archaeology should be about connecting people with their past.

MT: Was the start of what would become Recycle Archaeology?

HW: Yeah, in 2019.

MT: So, the first steps then were finding some materials, finding something that was going to be thrown away. How did that happen?

HW: Well, because of the sort of policy levels shenanigans, which, fortunately, I didn’t pursue. I had made a few contacts. I already knew Micol Stocco, who’s in charge of the Archaeological archive at Museum London, so she put me in touch with a large volume of material. Which is what’s called unstratified material archaeologically. So, it lacked the particular documentation, which meant that it wouldn’t fit within the collection development policies of their museum. This was material that had been dug by community groups largely in the 70s and 80s, so it was material that had been collected by a local community for a local community, but hadn’t managed to for whatever reason, get enough money behind it to become the sort of facility they wanted, and it was literally headed for the skip like in within days. So, it was kind of a difficult situation, because it was one of those situations where, it’s a bit like, if you don’t do this now this kitten is going to be put down. I just thought I’m just going to hire a van and put it all in my front room. So that’s where we are at the moment. The Recycle Archaeology stores is in my front room. I have only, and this is a small proportion of the material, about 12,200 artefacts.

MT: A lot of artefacts to have.

HW: That’s an estimate based on counting how many artefacts there are in each box and then multiplying it.

MT: I guess that’s probably only a small fraction of what is thrown away every year.

HW: Yeah, I mean because of the nature of that collection, it was quite a sizable amount of material that was going to landfill. The majority of stuff that goes to landfill is not as big. Most archaeological projects in the UK will be small evaluation trenches and things like that. So, it’s just maybe a handful of objects for a project like that, that could very easily be slipped in an envelope and be sent to Recycle Archaeology that at the moment, is going to landfill.

MT: When you’re talking about being sent to landfill, is that literally just being thrown in a skip, or are there other when options when these objects are being disposed of? A member of the general public would have no idea what that means. When you’re working with people and explaining that these objects are thrown away. Well, what does “thrown away” mean?

HW: More usually on archaeological sites, or it should be the case now, that things on sites are only disposed of once they’ve been looked at. So that everything is looked at before it’s thrown away. It’s not just discarded out of nowhere, and generally, there are policies about the sort of thing that will get rid of. So, for instance, ceramic building materials like brick and tile, probably about 90% of that is discarded. A fair amount that is discarded on site, bricks, for instance, are often left in the trench. That is a form of throwing away that is very common. If you’re excavating, say a post-mediaeval industrial site, you’ll probably have a large quantity of girders and things like that, you won’t be able to move off site and usually, you’ll leave them there. Record them and leave them in situ. Or, you know, building foundations and things like that. You wouldn’t collect those for a museum. So that’s one sort of throwing away. The other sort of throwing really is the stage that I’m probably more interested in, which is when things have gone to finds specialists and the finds specialists in their report says. “Keep this bit, but don’t keep this bit”. That material, I’m quite interested in getting for Recycle Archaeology. I have not yet got that material, so that’s one of my major concerns at the moment, getting in touch with the finds specialists I know to try and get them to start sending it to me, because at the moment, they give it back to the archaeological units, and they will put it in the bin.

Methods for community engagement through archaeological reuse

To explore how cultural organisations might engage with the reuse of archaeological de-selected finds through community-centred projects, I outline three focus areas for intervention: education, social and creativity. These themes aim to support and provide benefit to the public outside of current archaeological practices and develop new opportunities between communities and the cultural sector that were previously unavailable under current collections frameworks. Through discussion of the benefits of working with non-accessioned objects with Dr Wickstead, cultural organisations wanting to work with their collections in these ways are faced with conservation standards and collections management policies (Museums Association, 2016, 2014) which inform the rigorous process of deaccessioning collections objects. The deaccessioning of archaeological archives was established to be largely impractical during the rationalisation study by Baxter, Boyle, and Creighton in 2018, and thus, this paper seeks to establish new pathways for cultural organisations to recycle archaeological finds meant for landfill, which would allow for new ways of engaging community partners with artefacts outside of their collection’s standards.

Education aims to work with education sector partners to develop uses for the de-selected finds to support learning, research opportunities and skills development in students of all ages.

Social seeks to engage local communities to develop projects which benefit the public’s understanding and access to heritage and new explorations of heritage within local contexts.

Creativity seeks to reuse and recycle by using heritage as material for creative practices by artists, crafts and trades peoples. Transforming heritage into artistic material for creating artworks which may choose to engage with the historic and social legacies of these de-selected finds or pose an alternative for more destructive methods of disposal (e.g., grinding into dust).

In partnership with Recycle Archaeology, we established two pilot projects aligned with these aims. To evaluate the impact of these case studies on the public and partner organisations, I use a mixed-methods and practice-based approach. Written feedback, practice outputs and observation of community participants will be used to evidence how these projects create opportunities for the reuse of de-selected finds and how audiences would like to see these objects be reused in the future. To explore how the public, community partners and cultural organisations re-value de-selected archaeological finds, I will explore how the archaeological, social and personal values can be expanded upon and created through creative community reuse of these finds and how these community-led projects can add new ways for the public to benefit from participating in archaeology and cultural activities. Interviews, surveys, and qualitative engagement data will form new knowledge of what kinds of values are created through these creative projects and what benefits the public participants and cultural organisations gain through reusing archaeological materials. For these pilot projects, our cultural sector partner is Kingston Museum. Kingston Museum is in the town centre of Kingston-Upon-Thames. In September 2021, Kingston Museum opened Climate KAOS (Kingston Museum, 2021), a contemporary exhibition on the climate crisis, social responsibility and recycling, which formed the thematic basis for the museum to engage their local audiences in how to ‘recycle archaeology’.

Case Study One: School museum boxes

Museum studies have long connected school visits, handling collections, and free choice learning (Falk and Dierking 1997, 2013; Hooper-Greenhill, 2007) with impactful and long-lasting learning for families and school-aged children. Falk and Dierking’s 2013 revision of The Museum Experience connects this long-term learning not just through the experience of exhibitions they visited, but also programmes they had taken part in. Through this research, we know that the things most memorable for audiences of museums are often related to activities, objects and social interactions, and that this learning was best retained by those visitors who shared their experiences with friends or family (Falk and Dierking 2013). Learning in museums happens differently than in more formal education, informed by personal needs, prior experience and interests (Falk and Dierking 2013), whereas formal education follows set curricula, lesson plans and quantifiable education goals for students. To bridge the gap between museum learning and formal education, this project aims to translate the personal investment and sharing of museum learning to support more embodied learning in formal education environments.

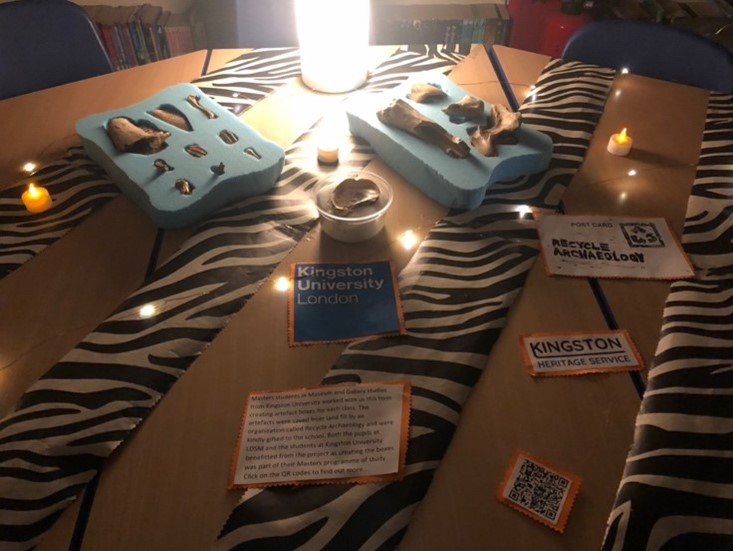

In September 2021, I established a working relationship between current Kingston Museum staff and Kingston University (KU) and Recycle Archaeology. This took the form of two proposed projects, the first being the development of recycled handling boxes inspired by the Climate Kaos exhibition (Kingston Museum, 2021) by Dr Wickstead’s Musuem and Gallery Studies MA students. These handling boxes would then be displayed in their community display case at Kingston Museum. Dr Wickstead facilitated this project through the first semester of her Museum & Gallery Studies master’s, scheduling sessions with the primary school partners and developing a lesson plan to engage her students in topics of museum education, collections management, object handling and research skills. The students created handling boxes along professional museum standards, researching the kinds of materials they would need, writing labels, and a teaching guide around their selected objects. The students then ran handling sessions for two local primary schools, St. John’s Church of England (CoE) Primary & Nursery and St. Mary’s Long Ditton CoE Primary School. KU students identified small collections of objects from the Recycle Archaeology stores to develop their research interests. The topics chosen by the students covered a wide range of subject areas:

- Animal bone and identification butchery marks.

- Medicine bottles and local industry.

- Clay pipes and the social history of British tobacco use.

- Chinese porcelain imported to Britain.

- British 17th and 18th-century ceramics.

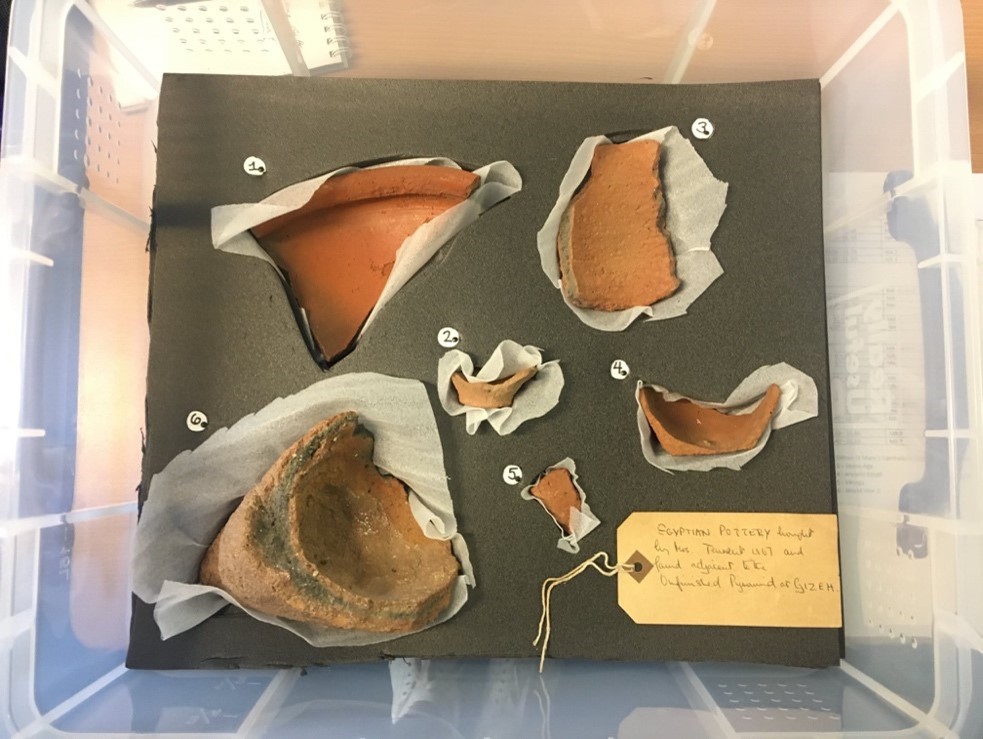

- Egyptian pottery and its social/ceremonial use.

- Mud larking and coin identification.

My involvement in this project is an assessment of the Kingston University students after completing their handling boxes and responding to a survey evaluating their experience working with Recycle Archaeology. All respondents displayed knowledge of collections conservation standards regarding their chosen materials for their handling collection, referencing creating a “cavity mount”, “foam mount” or referenced specific materials such as “ethafoam cavity mount” and “a clear plastic container”. They also articulated new subject knowledge and explained their planned handling session activity. Primary school partners kept the recycled boxes in their classrooms to develop creative projects around what they had learned and how it relates to their school curriculum. These school projects were displayed in an evening exhibition at the school, transforming classrooms into creative displays showcasing different projects and short films sharing what they learned with their families. In this case study, I will look at two student curator-developed handling boxes and the feedback and creative responses received from the primary school partners.

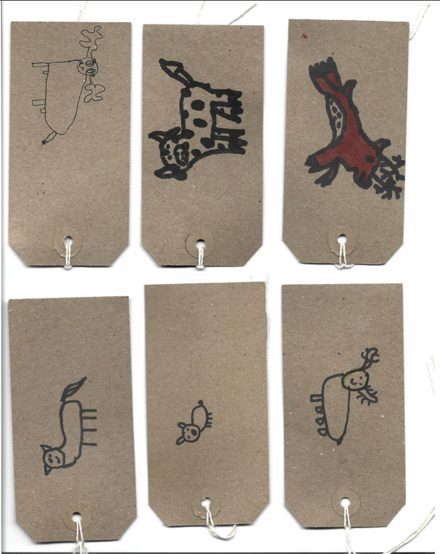

Year 3 primary school handling box: Animal Bones

KU student curator chose a variety of animal bones (Figure 2) and reported in their evaluation survey that they learnt “how to identify bones and some of the reasons for the differences in their appearance as a result of where they were found”. The KU curator led an activity session about how to identify the animal bones, and the Year 3s created their own labels (Figure 4) to accompany the box. Their enthusiasm can be seen through the feedback from the Year 3 primary students, shared through recorded short films during their school exhibition. This group of Year 3 students can be heard explaining that:

“That’s a chicken bone chicken [sic.] bone, this we think is from a cow.

Where’s that horn? Maybe a giant tooth? From some sort of…we guessed that was a whale, but they said it was either from a pig or something and we think this might be from a deer…

Most of these are cow bones because farmers have mostly cows, and since there are lots of cow bones, most of them go to the museum. That’s why most of them here are cow bones ’cause most of them don’t really have homes and museums.”[1]

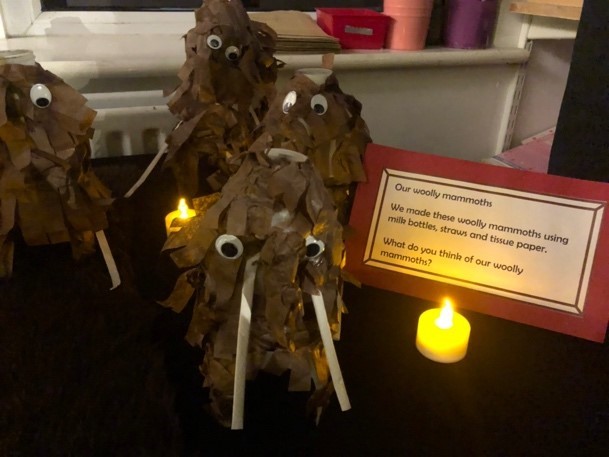

Through these recorded reflections from the primary students, we begin to see the impact these handling sessions had on the young learners. The students were able to express in their own words why Recycle Archaeology and Kingston University were working with the heritage objects, the issue present with museum retention of these objects, as well as explaining where these bones came from and their own ideas about identifying them. During the school exhibition, the primary students designed, decorated and contributed to a series of creative projects inspired by the handling collections and their history curriculum. Students in Year 3 linked the animal bones to their study of prehistory, created a series of pinch pots out of clay (Figure 6) and created woolly mammoths (Figure 5) out of recycling and craft supplies.

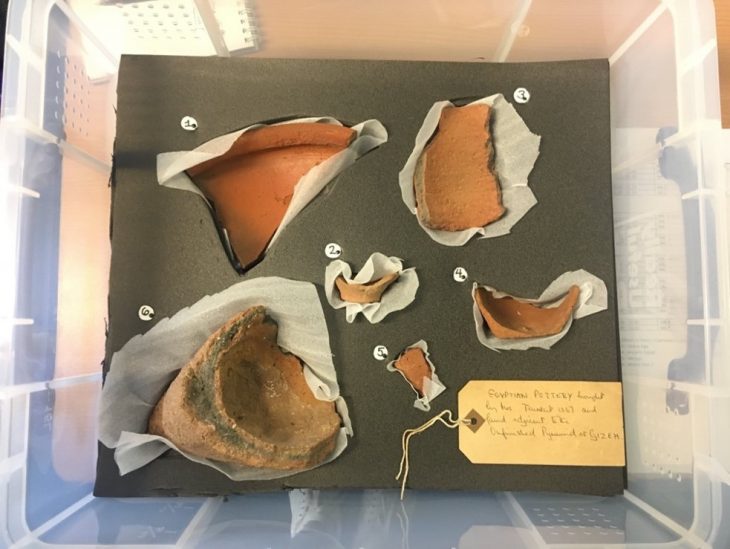

Year 4 primary school handling box: Egyptian pottery

The KU student curator who developed a handling box of Egyptian pottery (Figure 7) reported that they learnt about 4th dynasty (c. 2600 BCE) pottery and developed a new understanding of “how those in ancient Egyptian society might have been paid for their labour, and the methods in which they made their pottery”. Their activity for the primary students consisted of taking turns guessing what the object could be, then passing it around the class and allowing the students to handle each object. They reflected that they felt the impact of their activity with the primary school students was that “it is such a powerful experience for young people to gain an understanding of how similar our experiences today are to those of the people living thousands of years ago. By having the chance to see, touch, and experience first-hand these everyday objects, they can begin to notice similarities between the objects and objects they may use in their own life”. The primary school students expressed their excitement about learning Egyptian pottery, saying in their recorded short film that:

“Primary Students Group 2: This pot used to hold grain. And it was for weighing the grain, so each worker would get exactly the same.

Primary Teacher: Fantastic, OK, so what time period are the ceramics in front of you?

Primary Students Group 2: Ancient Egyptians

Primary Teacher: Egyptians OK, so you’ve actually got in front of you there some artefacts are actually from ancient Egyptian times, so we’ve got any idea how old they are?

Primary Students Group 2: Probably about 3000 years old.

Primary Students Group 2: It has been very interesting, especially when we discovered that five and three fit together and it was very interesting so. We’re just glad that we got to them to work.”[2]

The primary students who engaged with the Egyptian pottery handling collection were able to explain what the objects in the box were, how they were used, and identify the approximate age of the artefacts. On top of this, the students were able to explore how these vessels may have looked whole, having discovered that two of the sherds fit together. The Year 4 classrooms were decorated to represent the research they had done on Ancient Egypt during the school curriculum, with prints of hieroglyphics, creative projects related to mummies, and burial traditions (Figure 9).

Discussion

Through these two handling box examples, we can begin to see what an embodied practice of Falk and Dierking’s free choice museum learning might look like with primary school partners. This case study expands on the historical contents of handling collections and develops new forms of values by engaging community partners. Through handling sessions taking place in the classroom, the KU student curators are bridging the gap between museum and school learning. This gap then becomes a conversation, with students of all ages in dialogue, creating new meanings and uses for these recycled objects. With the KU students designing teaching activities and the primary students writing labels, the handling boxes become an object with multiple voices informing its use. These conversations open space for handing collections to engage more inclusively with their intended audiences. Not only to make the experience of a handling collection more participatory but to broaden how community partners engage with heritage objects, in their language, uses and needs external to GLAM needs. This begins to unpick how cultural organisations could create space for community voices in the activities and objects within their programmes, without siloing community contributions and reemphasising the authority of the GLAM voice.

Case Study Two: Community mosaic

This reuse of heritage as material is informed by the study of material culture and archaeological making as established by Tim Ingold (2007, 2013) and Haidy Geismar (2018) to further inform how artists may find creative value through de-selected finds and reframing artefacts through a community lens. Regarding the lifespan of an object, Ingold explains that “despite the best efforts of curators and conservationists, no object lasts forever. Materials always and inevitably win out over materiality in the long term” (Ingold, 2007, p. 10). Through this materiality of objects (e.g., the context surrounding it, which informs its social/historical/cultural meanings) inevitably the object is always changing. This change is the lifecycle of material, the stone, the iron, the cloth, not of the meaning made from how humans interacted with it. Ingold describes this change as “the stories of what happens to them as they flow, mix and mutate” (Ingold, 2007, p. 14) and is expanded upon in a later paper, describing the lifecycle of a marble statue. Carved from the earth and sculpted by humans, the statue will continue to change and morph as it “is worn down by rain, the form-generating process continues, but now without further human intervention” (Ingold, 2013, pp. 20-21). Ingold moves away from understanding through human interaction, and towards a more sensory and practical engagement with material itself. Geismar outlines how artistic and digital intervention can make space for a wider engagement and understanding of materiality and material of objects within GLAM collections, even when the physical material of the object is deconstructed or destroyed in the process (Geismar, 2018).

Exploring how the recycling of archaeology may inform on-site community programming at Kingston Museum, I proposed a partnership with Kingston Museum and local mosaic artist Kim Porrelli from the community organisation Save The World Club. Save the World Club, established in 1985 aims to empower communities to initiate environmental activities to ensure a sustainable future for all. On November 6th, 2021, Kingston Museum hosted a public workshop with Recycle Archaeology and Save the World Club to co-create a community mosaic. From my observations, the session was attended by a wide and diverse audience, I had discussions with students from Kingston University who had taken part in the Museum Box project, families with their young children who had learned of the museum through the children’s primary schools, members of the museum’s Young Peoples Collective, artists interested in mosaic making, adults with an interest in archaeology and retired locals who wandered into the museum just to see what was happening that weekend.

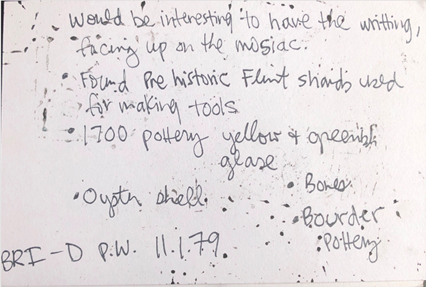

Developing community curation

To establish an ethos of community curation, attendees were instructed that they would be opening boxes of finds, facilitated by Dr Helen Wickstead (Figure 10), to nominate objects to contribute to the mosaic and generate ideas for alternative uses for the de-selected finds. During their excavation of the archive boxes, the public identified “pottery”, “flint”, “bones”, “bricks”, “iron” and “oyster shells” on their comment cards to be included in the mosaic. They noted that it “would be interesting to have the writing face up on the mosaic (Figure 11)” framing the objects within their original archaeological contexts. This process of community choice of use and value is something intend to dive into a little deeper.

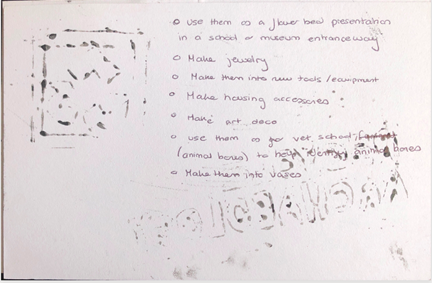

The public often referenced the objects with their respective site codes, dates, and name of the archaeologists who had found them. The public identified not only historic value attributed through the act of excavation, but social value of who those archaeologists were, where they were working and how this reflects in their understanding of their local area. By engaging with archaeological value at a community level, Recycle Archaeology can make the languages, processes and sectors of archaeology more accessible to non-authoritative communities and widen the understanding and importance of the continued preservation of archaeological finds. The public proposed new uses for the de-selected finds, suggestions falling between creative and educational outcomes. Some objects were posed to be made into “accessories, like necklaces”, “use them as a flower bed presentation in a school or museum entrance way”, “make them into vases”, or “make housing accessories” (Figure 12). Whereas others suggested educational and curatorial uses: “school exhibition”, “see them go to vet school to help identify animal bones”, and “pottery artefacts/remains can be used to make students/people imagine what the whole object would look like whole by looking at one piece of it”, or “wooden & pottery materials can be used as donations to students of archaeology, museums conservation & preservation departments to work on & develop their skills & new ideas around it”.

By exploring ideas of how de-selected finds might be used within their communities, making new objects out of these finds becomes a transformative process, a ceramic sherd becomes a community flowerbed, broken Chinese porcelain becomes unique earrings from a local craftsperson and clay pipes become a talking point built into the tabletops of the local pub. This becomes a curatorial choice by the public through the deliberate action of choosing what object deserves to be used as material, what objects have other uses and what objects get left in the box. This choice adds new dimensionality to these de-selected finds, outside of archaeological value, and speaks directly to the social values these de-selected finds have to the public, giving them direct access to artefacts they would only previously be able to see behind glass cases and engaging directly with history excavated from their local area. The public also was able to create their own personal values, deciding how else they would use the objects themselves or like to see them used elsewhere in their communities.

When interviewed about the impact of the workshop, the Education Officer at Kingston Museum described the community reuse of de-selected finds as something which will “preserve the value of those ancient objects but using a contemporary language” while also establishing the mosaic as a community-centred contemporary collections object which “will speak to the time. So, for decades to come, the curators at the museum will be able to use it to tell the story of this period when we were worried about preservation and sustainability”. For the museum, this workshop came at a critical time, having been closed for two years throughout the Covid-19 pandemic and only reopening its building in July 2021, facilitating and strengthening existing community ties (Save the World Club), and allowing for the development of new ties with the potential for long-term development (Kingston University).

Artistic transformation of heritage

Exploring how artists can transform artefacts meant for disposal, I discussed with artist Kim Porrelli from Save the World Club about her experiences working with Recycle Archaeology and the impact the workshop made on the public. We discussed the role participation and community engagement played within her art practice, and how through the workshop the public “too could become amateur archaeologists and have an input into a public piece of art that they wouldn’t have been able to do before”. The success of this community mosaic lies in the interrogation of heritage as material and how artists might reinterpret and shift the material with sensitivity or abandon the materiality which surrounds it. This as a process unearths where the value of an object lies, in constructed materiality or the material of the artefact itself. The creation of the mosaic is formed of aesthetic values, the balancing of shape, texture and colour while also working with a wide variety of media. The materiality of these objects (archaeologically and socially) is reinforced by being collected as a museum object, displayed in future exhibitions, and held within a museological context. This begins to pick at the different motivations for the development of community-engaged social and personal values. Kim explains in our interview that she engaged the public in conversations about how mosaics are made and how the material affects the process of making. This fits more in line with Ingold’s exploration of material, through sensory and practical exploration than with the materiality of the object which was attributed during the excavation of the boxes. By the end of the workshop, we did not have a collection of artefacts, we had a mosaic. An object made of individual values combined to create a new, whole identity separate from its parts. The individual pieces lose their materiality as single objects when viewing it as a mosaic, however, have the potential to expand outwards again when given the space digitally.

Discussion: Developing digitally

Figures 15, 16, 17: Initial tests of 3D Scan of the community mosaic from Kingston Museum (© Kim Porrelli, Kingston Museum, Recycle Archaeology, Treloar) (Treloar 2022)

The next steps for the community mosaic and the partnership with Kingston Museum is a series of workshops to digitise the community mosaic. To build a sustainable framework for continued digital community engagement with Kingston Museum, I deemed it important to work with accessible, free programmes on this project to avoid negatively impacting the digital capability, time of staff and available budgets. I developed an initial test of the free application 3D object and LiDAR scanner app Polycam available on Apple Devices (Figures 15, 16, 17). From July to September 2022, I will host a series of workshops for Kingston Museum Young Peoples Collective (YPC) members, introducing them to museum digitisation, Polycam 3D scanning and object label writing with the aim of the YPC members to develop their voice and text for a series of digital objects displayed on the museum’s website. This project will build off Geismar’s (2018) digital object research, exploring the hybrid material and materiality of the mosaic as a digital and physical object through further public participation and foregrounding the community voices which built it, digitised it, and invite further public participation once live online. This aims to foreground community voices within their collections, build a sustainable format for the engagement of community partners, and enrich the commitment of diversity and accessibility from the museum to their audiences.

Conclusions

Calling for the development of interdisciplinary collaboration

Through the workshop, the museum audiences were able to engage with the historic and social values from de-selected finds by identifying objects for creative reuse and suggesting alternative uses for these objects to engage further within their local communities (schools, universities, homes) and importantly established their own personal and communal ownership over the individual objects and co-created mosaic. By engaging the public and community partners in new ways of reusing archaeological material, students, families, artists and members of the public were able to access archaeological finds and heritage programming in new ways through Kingston Museum and Recycle Archaeology. As this partnership continues to develop digitally and communally, I hope for further engagement from the museum’s community partners to share space within the museum and develop sustainable workflows and development structures to continue future hybrid community engagement across new programmes.

This paper calls for wider interdisciplinary and cross-sector collaboration between archaeological stakeholders, cultural organisations, local communities, and Recycle Archaeology. I hope this paper sparks inspiration for how cultural organisations may help lessen the disposals of de-selected finds and engage their audiences in new co-creative ways of embedding community participation, voice and experience in GLAM programming and collections. The next step in my research aims to continue to develop spaces for artistic reuse and community engagement between Recycle Archaeology and other cultural organisations. If artefacts are suitable for landfill, why can’t they be suitable for recycling? The public and partners I worked with during these two projects were able to tell us what they’d like to do with these finds: make a mural, design new kinds of jewellery, decorate their garden beds, work with local schools, and provide learning opportunities for the younger generation. Given access to such exciting materials as locally excavated 17th and 18th-century medicine bottles, animal bones or ceramics, what could you and your communities do?

[1] Transcript of Year 3 primary student feedback (Treloar, 2021)

[2] Transcript of Year 4 primary partner feedback (Treloar 2021)

About the author

Marley Treloar is a PhD researcher at Coventry University studying hybrid digital participatory practice and community engagement. She graduated from Kingston University MA Museum and Gallery Studies in 2019 and has worked across the arts and heritage sector working as a freelance Curator and Education and Engagement officer. Marley is a member of the Artworks Alliance participatory network and Museums Association.

References

The Audience Agency (2021) COVID-19 Cultural Participation Monitor Summary Report: Digital Hybridity. Available at: https://www.theaudienceagency.org/evidence/covid-19-cultural-participation-monitor/digital-hybridity [Accessed 2 April 2022].

Baxter, K., Boyle, G. and Creighton, L. (2018) Guidance for the Rationalisation of Museum Archaeology Collections. Society for Museum Archaeology.

Boyle, G. Booth, N. Rawden, A. (2016) Museums Collecting Archaeology (England) REPORT YEAR 1: November 2016. Society for Museum Archaeology.

CIfA (2019) Toolkit for Selecting Archaeological Archives. Chartered Institute of Archaeologists. Available at: https://www.archaeologists.net/sites/default/files/downloads/selection-toolkit/SelectionToolkit_3_thetoolkit.pdf [Accessed 2 December 2021].

Dierking, L. D., & Falk, J. H. (1997). School Field Trips: Assessing Their Long-Term Impact. Curator, 40, 211-218. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.2151-6952.1997.tb01304.x

Falk, J.H., & Dierking, L.D. (2013). The Museum Experience Revisited (1st ed.). Routledge. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315417851.

Geismar, H. 2018. Museum Object Lessons for the Digital Age. London: UCL Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.14324/111.9781787352810.

Hooper-Greenhill, E. (2007). Museums and Education: Purpose, Pedagogy, Performance (1st ed.). Routledge. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203937525.

Hooper- Greenhill, Eilean. (1994). Museums and Their Visitors. London and New York: Routledge.

Ingold, Tim. (2007). Materials against Materiality. Archaeological Dialogues 14 (1): 1– 16. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1017/S1380203807002127.

Ingold, Tim. (2013). Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art, and Architecture. London and New York: Routledge.

Jenkins, H. and Ito, M. (2015). Participatory culture in a networked era: A conversation on youth, learning, commerce, and politics. John Wiley & Sons.

Kingston Heritage Service. (2022), Kingston Museum. Available at: https://www.kingstonheritage.org.uk/ [Accessed 2 April 2022].

Marco Mason & Giasemi Vavoula (2021) Digital Cultural Heritage Design Practice: A Conceptual Framework, The Design Journal, 24:3, 405-424. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1080/14606925.2021.1889738.

Museums Association (2014) Disposals Toolkit: Guidelines for Museums, Museums Association Website. Available at: https://ma-production.ams3.digitaloceanspaces.com/app/uploads/2020/06/18145447/31032014-disposal-toolkit-8.pdf [Accessed 2 April 2022].

Museums Association (2016) Code of Ethics for Museums, Museums Association Website. Available at: https://www.museumsassociation.org/app/uploads/2020/06/20012016-code-of-ethics-single-page-10.pdf [Accessed 2 April 2022].

Museums Association (2021) Redundancies in the museums sector after one year of Covid A review of Museums Association Redundancy Tracker data, Museums Association Website. Available at: https://ma-production.ams3.digitaloceanspaces.com/app/uploads/2021/06/22110841/Redundancy [Accessed 25 April 2022].

Recycle Archaeology (2021) Animal Bones Handling Box Facebook Post. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/Recycle-Archaeology-261948222322150/photos/312446147272357 [Accessed 2 April 2022].

Recycle Archaeology (2021) Ancient Egyptian Pottery Handling Box Facebook Post. Available at: https://www.facebook.com/Recycle-Archaeology-261948222322150/photos/306804254503213 [Accessed 2 April 2022].