Encouraging the Authentic-Self: Inclusive Design Research Methodologies for Higher Education

Dean Fallon and Michelle Wetherell

Download the PDF of this article

ISSN 2752-3861

Abstract

In design, pedagogies utilising strong individualistic research, can successfully provide a rich foundation for all projects, and are essential for developing unique and innovative outputs. Although Gen Z students are offhandedly known as digital natives a 2017 study (Moore, Jones and Frasier) showed the majority were over-whelmed by the sheer volume of internet sourced information and had difficulties accessing the perceived ‘correct information’, and additionally needed assistance in processing information collated. The COVID – 19 pandemic has further compounded the issue by increasing the disconnect with the physical research experiences which have historically provided the inspiration students needed. Individual research is now harder for students to obtain, process, and understand, within a saturated landscape.

This paper aims to establish design mechanisms, addressing problematic understanding and imposter syndrome in design students. Asking whether personal student heritage and experience can be utilised as a threshold concept in the delivery, and understanding of, pedagogical design research. In doing so can such methods encourage authenticity, facilitate socially inclusive teaching tools, and develop a research spring board; rethinking how research methodologies are taught to empower students to enquire, understand, and build connections throughout their design practice? The paper looks at adaptions of established methodologies such as Martin Raymond’s Cultural Triangulation (2010) applied in alignment with the Socially Inclusive Teaching as Pedagogic Work; ‘Belief’, ‘Design’ and ‘Action’ (Gale et al., 2017) provide the grounding frameworks. The discussion expands on evolving design research practices, supported by HE student case studies and focus groups.

This article questions whether students form deeper connections to research if the research is linked to their experience, and suggesting methods on how educators can embrace and value the individual by involving them as key, active participants whilst driving a transformative effect on their design research understanding.

Introduction

This article disseminates practice-led research and applied theoretical models to cultivate the authentic-self in design pedagogy for higher education. In this instance, experience in teaching fashion design at undergraduate [BA Honours] level in the UK lead to valuable empirical evidence, utilizing student consultation, interviews, and responses to assist proactive curriculum design with the opportunity to test and creatively adapt relevant theoretical models. Recognition of reoccurring themes and habits in practice, breeding both positive and debilitating experiences, presented an outline for the research. Generational challenges in sourcing, processing, and applying information to instigate design, are presently compounded by growing anxiety or ‘imposter syndrome’, stemming from a student’s lack of belonging and/or relatability to the educational setting or task in hand.

Piloting ‘cultural triangulation’ to simplify and structure research methods whilst initiating ways in which to empower the learners background, formed a foundation to challenge disconnect and ways in which to use the ‘self’ more profoundly. Thus, representing an overarching intention to elevate, innovate, and captivate students across the design curriculum. As an engaging pedagogical tool, this paper and on-going research divulges how the student journey and output can notably be strengthened, effecting the experience and skillsets of all stakeholders involved [subjects/ learners/ teachers/ audiences].

Upon observation, applying such mechanisms holds the potential to positively propagate into design enquiry, embedding knowledge of authenticity, acceptance, and innovation into an individual’s processes. In the broader context, the mechanisms can accommodate the values of equality, diversity, and inclusion through design cognition, to effect the student and lecturer. This article intends to methodically navigate the research focus; from outlining generational, social, and academic trends and challenges currently effecting art and design cognition, leading into a reflection of techniques that hold the potential to help liberate creative practices.

Setting the scene, The issues

Most UK students enter university from a UK educational structure at Secondary and Further Education, which from experience can formalise, control, or hinder the individual enquiry and engagement with creative knowledge and processes. Art and design educational practices in Higher Education can be seen to be at odds with their experience of this ‘traditional’ learning. For post pandemic students the transition has been further affected, and the students’ sense of traditional learning has been disrupted. Recent literature (Eyles et al., 2020) highlights the effect of COVID 19 on students entering university including a loss of face-to-face teaching, cancelation of exams and a disproportional effect on disadvantaged students. Raaper & Brown (2020) appeal to educators to recognise that the dissolution, disparity and inequalities amplified through covid may affect student motivation and self-discipline. Pownall et al. (2021) explore issues facing future cohorts and suggests key considerations for educators, including awareness of increased Imposter Syndrome and the need to develop a sense of belonging in the student cohort. Ramsey and Brown (2018) imply that a part of Imposter Syndrome is a belief by the student that their place at university has not been ‘earned’ and this is often linked to lower self-esteem; students suffering with Imposter Syndrome tend to either overwork out of fear or underperform as they believe failure is unavoidable. Pownall et al suggests creating a sense of student belonging may combat Imposter Syndrome, and Pajares’ (2001) study suggests authenticity and self-acceptance are connected to academic achievement, confidence and positivity.

As well as the general effect of COVID 19 on the whole student population, students entering art and design education have been impacted further by the lack of studio time, and physical hands-on learning, which is intrinsically linked to their practice. Within art and design subjects it can be argued that research, starting points and concepts, are the foundation of the students’ work and the springboard to successful ideation, curiosity and design thinking. However, based on student observation, interviews and teaching experience, asking students to begin projects by developing “a research starting point” without methods and/or constraints can lead to doubt, confusion and feel too ambiguous and can become a barrier for a learner coming from the more traditional Further Education and Secondary environment. This can lead to a problematic start for projects and have a negative impact on student learning and their broader student experience. Students’ struggles with design research is well documented. Akalin & Sezal’s (2009) paper on architectural design education suggests that a combination of limited student experience in observing, perceiving, understanding and visualising, coupled with a lack of “formal” methods within their design practice confuses each new cohort. Whilst White’s (2019, p. 802) paper on Inclusive Creative Methodology for Design Research states, “to give a student who may not be naturally predisposed, the elusive command ‘be creative’ leads to frustration, disorientation and, potentially, feelings of inadequacy”.

Carlson and Dobson (2020) make the case for encouraging students to embrace ambiguity, empathy and to adopt artistic thinking to develop design learning but they also highlight the associated challenges facing students from a formal education. This is a perhaps a process of deprogramming and can be conflicting, “They (students) must navigate and manage both the artist voice (What do I want to do?) and student voice (What is excepted of me?)” Carlson and Dobson (2020, p. 436).

Both Foley (2014) and Dineen and Collins (2005,46) note that the creative process must be discovered by the student, and both liken this to an individual journey of discovery. Orr et al, (2014), advocate a shared responsibility for learning, encouraging students to take responsibility for the direction of their work. Their research also looks at the student’s perspective through interviews, “They [the lecturers] don’t spit it out for you but they get you to think, and sometimes that can be frustrating because when they’re not telling you the answer because there is no answer” (Orr et al., 2014). This highlights the confusion and frustration in the transition to independent learning in relation to art and design, and the complex nature of the student/lecturer relationship.

When asked to create their own concept, or research starting points, lecturer observation has shown that the endless possibilities can actually stifle students, a concept echoed by Chen’s (2015) research into the learning problems of industrial design students, noting that the top two issues were concept generation and design research.

Our current generation of students, who mainly consist of Generation Z (Gen Z) born between 1995 and 2010, have grown up with digital interactions and technology as part of their everyday life. With greater access to information and sources than previous generations. Stillman & Stillman (2017), noted that Gen Z students view the world differently to previous generations. For them the physical and virtual/digital world cannot be separated. The average Gen Z student typically uses digital technology for up to 10 hours a day (Kalkhurst, 2018) and as a result has developed an eight second attention span and can become easily bored. Kalkhust (2018) also states “Gen Z learners don’t see technology as a tool, they see it as a regular part of life”

Although Gen Z students are offhandedly known as ‘digital natives’, a 2017 (Moore, Jones and Frasier) study showed the majority were over-whelmed by the sheer volume of internet information, that they had difficulties accessing the perceived ‘correct information‘ in an educational setting, and needed assistance in processing the information they had gathered. This suggests that internet research can lead to option paralysis and the inability to decide, as well as analysis paralysis where overthinking leads to inaction. This also echoed by Shatto and Erwin (2016) who found that Gen Z students are reliant on the internet, but lack the ability to analyse information found. These studies, coupled with observations of Fashion design students, suggest that some students are in a state of cognitive dissonance in relation to internet research; they know it is not working for them, but they struggle to break their habitual reliance on it. As an academic and educator the answer to breaking the reliance on technology and the internet seems obvious – use the library. However, this is not so easy for digitally connected student learners.

Other observations and student interactions suggest that it is not uncommon for students to suffer from anxiety surrounding library use, which compounds issues around developing visual research. Though when you begin to unlock data surrounding this it is hard not to have sympathy with our Gen Z learners. Smith et al (2022) surveyed student study modes pre-HE and found, “only 27.8% stated that they had used books/materials in the school/college library” and only 1.2% of students stated library books as their main source of study post the 2019/2020 lockdown, down from 2.6% pre-lockdown. Student library use was shown to be the lowest study mode and had also declined post-pandemic, although these studies are not focused on art and design students it does give an overall objective view of student internet and library interactions.

These figures are perhaps more understandable when put into context against a backdrop of pre-pandemic UK austerity cuts. Between 2010 to December 2019 the UK government closed 773 public libraries (The Guardian, 2019) and The Independent reported in 2019 that 1 in 8 UK schools did not have a library space and this was disproportionally affecting the most disadvantaged students. “Findings indicate that pupils in schools with a higher proportion of free school meals are less likely to experience the range of positive benefits a school library can provide,” (The Independent, 2019). With libraries being less accessible than ever it is no wonder that many of our students predominantly turn, and return again and again, to the internet to source their information and research.

Unlike traditional ‘academic subjects’ where students are given reading lists sign-posting them to materials which may contain the “answers”, for art and design students the path is not so clear. Art and design students’ reading lists are often more technical in nature or supportive in craft and manufacturing.

If the path in art and design is too unclear, that the internet is too large a source, and that the library is too unknown, it is no wonder that our students struggle to form engaging design research. And in extreme cases to even start the research process itself.

Observations and interviews with undergraduate fashion students also reveal ‘a want’ to hurry through research to get to the outcomes/design stages, without building a solid foundation for the project. Here a student explains her initial approach,

“When I first started my degree my approach was very different I never found a theme that I was really passionate about I would kind of rush through the research and concept phase and start designing very quickly because that’s what I enjoyed the most”

This is a problematic response to both research and design as the ideation process can increase innovation, broaden ideas and develops concepts which, in the above case, have been rushed to get to a perceived comfort zone. White (2019) expresses “It is a challenge teaching design and craft while simultaneously finding ways of reducing the human desire to plan outcomes”. This suggest a greater need to engage at the research stage and that this could be done by developing active learning, and student-centered learning approaches.

Within the fashion design course the students’ Gen Z habits have led to an increase in repetitive and surface led research, coupled with a resistance to use the library independently, if at all. Within the same cohort, and sometimes even within the same class, students have been known to have the same research images. A reliance on the internet, similar interests, algorithms and echo chambers almost make this inevitable within the digital arena. Students notice this within each other’s work which can often lead to a lack of enthusiasm for their project, a notion underlined by the student below,

“Anybody could have done the same project as me”… “I kind of never took the concept to the next level, I realised that I got bored with my projects very quickly”

Here the student states that their research was not undertaken seriously or in-depth. The student then connects their research to boredom not only within the research phase but also for the rest of the project, which points to a lack of student engagement. The statement additionally emphasises a perceived lack of value for the research processes, and therefore, the impact of research which is often pivotal in inspiring students to create innovating design work.

However, how does a generation of students with increased Imposter Syndrome (Pownall et al 2021), ‘technologically enhanced isolation’(Carlson and Dobson, 2020 p.431), plus the fear of the library discover and embrace research?

This paper looks at inclusive and student-centered learning methods developed and experienced by undergraduate Fashion Design students. It focuses on breaking problematic research habits, leading to a transformative student experience. By encouraging students to become stakeholders in their education, and to start a journey of learning by embracing their authentic-self.

Empowering the Authentic-Self

By sympathetically acknowledging the continual challenges in the learner’s perspective; their foundation, experiences, and expectations, mediates the benefits for a co-learner approach in design education. This presented the pedagogical challenge as to how a student centred approach can empower the learner, as an individual, whilst being adaptable and relevant through the representation of design.

Concepts of society and cultural heritage, portrayed through visual communication and design, have previously been the subject of scholarly theorization. This can be seen in creative disciplines such as architecture and graphic design, which comparably to fashion, directly integrate into the fabric of society and cultural interpretations. Cultural heritage is a rich source of inspiration, providing “accumulated resources, both material and immaterial, which people inherit, use, transform, increase, and communicate” Leach (1997). Pilay & Neves (2020) draw on Leach to articulate the idea of cultural heritage as a resource for design research, as discussed in this article. To reiterate, this study focuses on fashion design practice, but the approach can be adapted for broader transformative learning across creative HE courses. Design is a reactive and visual reflection of society in itself, both as commodity and an art form, providing inspiration for research, as an aspect of the design process.

Through the Trend Forecasters Handbook (2010), Martin Raymond, reapplies the social science principles of triangulation to establish a comprehensive approach to trend research, rich in the notion that tracing and validating changes taking place within a culture can identify new trends & behaviors [Cultural Triangulation]. It is apparent that the signposted processes of enquiry: Intuition, Interrogation, and Observation, also present an effective way to assist a creative learner in scaffolding the demand to begin design research.

What originally developed as a framework to support students with the ambiguity in conducting creative design enquiry, unveiled a method to align greater individual empowerment and social inclusivity via personal up-bringing and experience. The theory of encouraging ‘personal heritage’ as a threshold research concept presents the opportunity for further connectivity, engagement, and confidence in the student’s thought processes and learning experience, which in doing so can confront the generational issues previously raised. Gale et al. recognise that sociocultural pedagogy “is concerned with the relationship between practice and the cultural, institutional, and historical contexts in which the practice occurs… What is fundamental is the relationship, how the social world, the individual as agent, and the practice are interconnected.” (2017, p. 346).

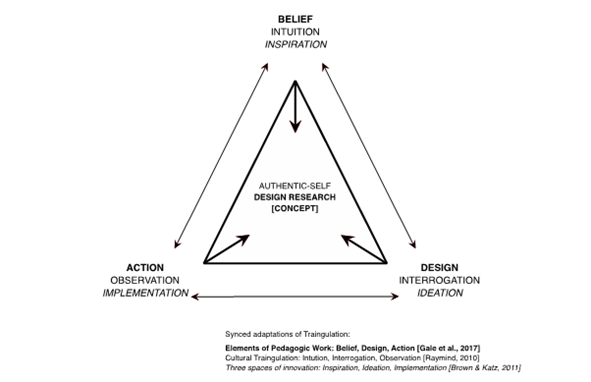

The adaptation of Raymond’s Cultural Triangulation presented synergies with Tanya White’s method ‘The 6Rs’ devised to nurture inclusive design research (2019). Which effectively expands on Tom Brown and Barry Katz’s (2011) pragmatic triangulated theory in differentiating the ‘three spaces of innovation: Inspiration, the problem or opportunity that motivates the search for solutions; Ideation, the process of generating, developing, and testing ideas; and Implementation, the path that leads from the project room to the market. However, the catalyst in contextualising a framework which critically positions the learner and teacher as the core agents of change was provided by Gale et al. (2017) re-establishing Bourdieu & Passeron’s strategy (1990): Elements of Periodic Work [PW]: belief, design, action. Gale et al. identify the core principle in implementing the PW triangulation to build socially inclusive pedagogy, focused on the individual student. The recognition that all learners enter a learning environment with an abundance of valued, applicable, knowledge and experience, has translated effectively when endorsing the ‘authentic-self’ in design cognition through this practice-lead paper.

Empowering a student’s past, knowledge, and experiences, instantly puts the learner at the centre of the research process and pedagogical application. In practice, it has noticeably enhanced engagement on multiple fronts, proving equally rewarding, and transformative, for all agents involved [learner/teacher/public]. Referring to one’s background, upbringing, interests, and experiences inevitably breeds confidence through familiarity at the critical starting point of a design process. Such research triggers can deepen appreciation and understanding for the researcher, actively connecting through enquiry and reflection to create stakeholders across the; subjects, creators, reciprocators, and receivers. As a process, it embraces the individual whilst fostering community and relationships for all parties involved. Here a student reflects on the process “working on a subject personal to me felt very natural and easy” going on to recognise that by taking inspiration from the people in their life around them, created those vital stakeholders to not only support the creator but innovate the design processes and outcomes.

Presenting the possibilities in applying personal influences/knowledge to unlock the ‘authenic-self’ has not only provided a voice for the creative learner to express oneself through their unique enquiry the consequential design work, but has equally supported students to comprehend or challenge various forms of scepticism, insecurity, and/or marginalisation they are encountering in, and beyond, the educational setting.

Methodology: An Adaptation of Triangulation to Facilitate the Authentic-Self

1) INTUITION / INSPIRATION / BELIEF: This symbolises the initiation of the process. It is important to give the student the licence to look at their own background, using natural responses to what they are connected to. The delivery of the task is key to empowering the learner(s), setting in motion the value of personal knowledge as ‘new’ knowledge when presented to other parties. Thus, providing a mechanism for innovation by naturally capitalising on non-internet, exclusive (to the learner) sources, avoiding general/prescribed references. By the teacher exposing an aspect of their personal heritage, and/or good examples of how such references can trigger, grow, and drive the design process, it creates assurances of new approaches and transitions the teacher to a co-learner; simultaneously breaking down barriers, building working relationships and networks that will prove invaluable going forward – ‘interpersonal cooperative learning’. Instilling the belief that the ideas/knowledge of which the student wishes to pursue is of great value, epitomizes the potential impacts in the learner being recognised as the true author.

2) INTERROGATION / IDEATION / DESIGN: Stepping beyond emotion, memories, interest, and pre-conception, the next phase asks for a deeper exploration of the starting point(s). What lines of enquiry can shed further light or detail on the point of inspiration (trigger)? Examples in practice include students informally interviewing family, friends, associates, to visiting locations, archives, fieldtrips, and gathering unique material: photography, artefacts, heirlooms, & memorabilia. Not only does the heightened interrogation help collate more innovative content, the process reinforces existing and enriches new connections with communities within and outside of the studio or classroom. In terms of the teachers role, the pedagogic design is still led by the student direction at this point, requiring the teacher to be reactively engaging and inquisitive to further promote critical investigation. Enabling and supporting the introduction of strong secondary associations should be encouraged to enhance the enquiry where appropriate, as part of the critical yet creative investigation. The chosen starting point will naturally be associated to a time and place, an era, a genre, a movement, (sub) culture, a location or event, any surrounding factors can be introduced to fortify or elaborate from the personal trigger. This notion places the learner firmly as the ‘creative director’ of the research, empowering further. Practice evidences the impact of creative license, with students and practitioners creating a muse, scene, or even world, that has stemmed from or is loosely based on a factual starting point, to design and define their research (design concept).

3) OBSERVATION / IMPLEMENTATION / ACTION: At this point inclusive opportunities to engage with course material and other forms of knowledge, or processes that resonate with the learner, should also be introduced; informing, progressing, and disrupting the research – ‘actioning’ initial design development. This is a clear moment where the design concept progresses from building a rich visual narrative to implementing design responses. Reflecting on the research amassed, the invested student should be able to confidently extract and explore: material, texture, silhouette/form, colour, symbolism, pattern, & styling. Of course, the research and development should be perceived as on-going, motivating the student to confidently revisit the body of research at any stage if stifled or devoid of the desired design direction.

From advocating the methodology, it is important to discuss the potential concerns endorsing personal heritage as a research mechanism can present. When planning the pedagogy and delivery it should be deemed as an example of an adaptable framework, non-prescriptive to all learners. Educators must be empathetic to every student, taking into account the circumstances and approaches of the individual. Requesting an individual to draw from and present an aspect of their personal heritage can evoke a great degree of trepidation, unease, which in turn can lead to understandable resistance or disengagement.

It is also key to note that the discussed method is not solely reliant on primary sources and content. The research starting point, no matter how rich or vague in obtainable primary material, simply provides a unique trigger for the student to creatively build from. The research already holds a degree of invested interest via the personal connections and early decision making.

When using societal and cultural references for design research and direction, appropriation presents another factor that requires attention, and a deeper understanding, from all intending agents involved. Utilising ‘personal’ heritage goes a long way to alleviating such issues, due to the fact the learner is interacting with aspects of their own background to re-communicate through their own creative aesthetic. As an effective mechanism to combat potential cultural appropriation through design, it encompasses the principle of ‘activation’.

“Activation in fact is aiming at reproducing and transmitting cultural heritage through an action of sustainable re-contextualisation and re-use of its values, in particular incorporating its qualities in new shapes, objects, artefacts, services, events and spaces. The heritage can be “activated”, dynamized, reproduced, renewed and re-generated (or “actualised”) in continuity with its tradition, but dialoguing with the contemporary context, thus mediating between conservation and innovation of forms, languages, aesthetics and values and their incorporation and creative re-use.” (Lupo et al. p .433).

The lecturer’s role: value, support, challenge

Part of the lecturer’s role is to encourage students to develop their ‘authentic self’. This can be done through a ‘soft approach’ to the individual student’s personal heritage. The prompt of “personal heritage” can seem exposing, it is therefore the lecturer’s responsibility to facilitate the student in understanding the term in a positive and non-judgemental way. And by realising the possibilities the topic presents in relation to themselves and the increased opportunities of a more individualised starting point. This helps students step away from digital research and enables them to build a rich visual language which is authentic, individual and engaging.

However, it can be an uncomfortable process for the student to engage with and to decide on what their ‘personal heritage’ is, and what ‘part of themselves’ they want share. “This artistic troubling of our identities, our beliefs, and our actions (and inactions) is often disorienting and almost always discomforting.” (Darts, 2004). Though ‘discomfort’ need not be a negative experience, and perhaps should be seen as something to encourage students to accept and embrace as part of the learning, and design process. However, as lecturers we are unaware of past student experiences and some students’ connection with heritage can be negative and upsetting and the prompt of personal heritage without context can be polarising and damaging.

It is therefore the lecturer’s duty to give context to the prompt of personal heritage. ‘Heritage’ can be taken in many different contexts, it has many possible meanings, and is increasingly fluid when you consider it in regards to ‘personal heritage’. It could be an aspect of culture, tradition and religion, and define what is important to us. This is expansive and can touch on languages, accents, dress, hobbies, festivals, food, pastimes, and music. The list is almost endless. Class, status and upbringing also have roles to play. As does direct personal experience, and those experiences of our family. All of these factors inform our understanding of who we are. Personal heritage can seem a profound topic but it can also be playful and fun. Students should be allowed scope to use this prompt to discover their authentic self in a way which is comfortable for them.

This exploration can be seen to change not only the ‘explorer’ but also the nature and subject of what is ‘heritage’. The key for our students is the ‘personal connection’ to their projects, for this to empower them, and for the students and lecturers to value their past experiences and background. Richens (1994) and Akalin & Sezal’s (2009) note that stronger students, and those who are confident risk takers, often use their own cultural backgrounds and self-expression to elevate their projects. Inclusive methods of seeing value in their past experiences can lead to a transformative effect, Gale et al (2017). The personal starting point also offers the opportunities for staff and students to develop a less formal relationship by promoting active engagement and helping break down the perceived hierarchy of the lecturer/student relationship by casting the lecturer as a co-creator (Dineen & Collins, 2005, p.46).

Within the fashion course we have had students create projects on parents’ careers (including a Jamaican hairdresser and a stay at home mum) to parents’ hobbies (including a motocross champion and a pigeon racer). Musical heritages, which had been inspired by parents, included a project on the New Romantics and another on a dad who was a Rave DJ. Other students have focused on more emotional concepts, including grandparents from the Windrush generation, and exploring Black female tropes in relation to their mum’s mental health struggle, some were quite an emotional investment. Tangney’s (2014, p.270) study Student Centred Learning: A Humanist Perspective, notes “It is difficult to create a piece of artwork without emotional investment or an emotional consequence” and highlights that students should learn to separate emotions in learning by developing strategies to create their work. Within this construct the lecturer can then be both supportive and challenging to the student in order to push the student’s development and understanding.

‘Emotional’ investment, within this paper, is considered to come from the student’s personal heritage and seeking of the authentic self. The ‘strategy’ or vehicle of learning which challenges the student comes from the triangulation methodologies, see figure 1. This strategy is helpful to separate the project’s staring point of personal heritage, and its connected emotional response, from lecturer feedback and engagement. Tutorials should therefore focus on the research journey and not overtly challenge the starting point as the student should be encouraged to feel that they and their experience matter. Mattering can solidify the feeling of being important and significant to others, and is central for well-being and increased student engagement (Flett, et al. 2019). Within any feedback and/or critique stages it is paramount that the student is supported and encouraged to reflect on how they have researched in relation to cultural triangulation, and be signposted to any supporting secondary research to develop their project if needed. This can be transformative in terms of improving the student’s emotional intelligence and their future response to feedback and reflection, as well as their approach to design research and ideation.

The lecturer’s role is highlighted by Orr et al, where the Art and Design students surveyed viewed the lecturer/student dynamic as a relationship where they (the students) are supported by lecturers and the key skill of the lecturer is to enable and empower (Orr et al., 2014, p.38). Here a student recognises the lecturer’s role in guiding and empowering them in their research choices,

“For my final project I initially worked on my country (France)…but my project stated to look like a history project erm, I was missing something personal something more connected to me, I discussed it with my tutor that really understood the mood of my kids wear collection and asked me the right question, he asked if I new anyone in my family that was quite rebellious when they where little? and it clicked straight away, I immediately thought of my nan and I new I was going to work on my nans childhood.”

The lecturer puts the student at the center of their learning, and the student goes on to be further motivated throughout the project.

“I moved away from my initial idea and focused more on my nan err because I had so much more to work with and I loved the new ideas and visuals which were added to my project. It made the design process a lot quicker and easier and I almost felt like I was getting to know my nan as a kid and that was really cool. I really think working on something you really like makes the whole design process a lot easier and enjoyable”

It is interesting to note that the student’s level of investigation and motivation increases by looking at research in a more focused, narrow and personal way. They now claim to have more research ideas and visuals based on their nan then they did on their initial broad and general topic of France. This seems counterintuitive, but this in-depth focused research helps for a more considered concept with the constraints creating an impetus for authentic, individual projects, which also combats the possibility of options paralysis.

Collins & Amabile (1999) discuss the powerful links between creativity and motivation, suggesting that creativity is fuelled by an instinctive personal motivation and the need to fill their potential, but they also highlight that creatives can become withdrawn by external pressures. If ‘lecturers’ are seen as external influencers, then part our teaching must be linked to how we motivate and encourage through our influence. Dineen & Collins, (2005) note that lecturers able to motivate and influence the atmosphere of the learning environment are the most successful at improving student’s creativity; additionally they also recongnise the damaging effect that negative feedback can have in undermining creativity. There are also other challenges within the art and design lecturer’s role, including the students’ perception of feedback. Orr et al.’s (2014) survey of students reveled that some viewed lecturer feedback in Art and Design as just an ‘opinion’ while others sought feedback from multiple lecturers which lead to conflicting views. Interestingly, students who sought multiple sources of feedback were at odds with the outcome yet still desired a consistent view. All these issues can be compounded when dealing with students whose work is also personal.

Conclusion: Concept currency and influence on cognition

The objective of the article is to expand on good practice, demonstrating how the application of a triangulated framework can empower all stakeholders in the research enquiry. In conjunction it is integral to acknowledge the distinct and sometimes complex variables of the individual (learner – creator).

Embracing ‘personal-heritage’ can noticeably bolster individuality and autonomy, enabling students to innovate their approach and context as a designer. As discussed, this empowers students to contribute their life and experience to their art and design education and practice. Sullivan’s (1992) much used quote around the relationship between art and life, “Individual and regional autonomy is emerging as the sort of strong cultural currency needed in an era of profound doubt and uncertainty.” seem even more relevant today than it did some 30 years ago.

The model of applying triangulation to facilitate the authentic-self introducers students to the teacher on another level, opening the door to new verbal and visual dialogue. In doing so, on every occasion, the teacher is presented with new knowledge and perspectives, effectively becoming a co-learner within the research journey; rather than prescribing or acting on, working ‘with’ the student (Gale et al., 2017, p. 351). As reinforced in the methodology [figure 1], if applied without pretense, the framework can create a space where multiple knowledges are equal, can co-exist, and cultivate throughout the learning community. The intention is to add equity to the learner, their cognition, versatility, and innovation. When engaging with the working world outside of academia, no matter the, size, level, or market sector of the employer or audience, the individual has a sense of self, alongside the ability to sensitively adapt to any given design brief.

Part of the journey as a creative in academia is processing conflicting views and navigating uncertainty, in turn providing a true reflection of a creative career. Cultural triangulation as a methodology, or simply encouraging one to tap into their past and experience, is not a one size fits all solution. Yet if approached with an open-mind and compassion, it can provide a unique framework for students to research, whilst developing a co-creator/facilitator relationship. In turn the process can initiate many students understanding, durability, and navigation through the ambiguity of art and design enquiry.

About the authors

Dean Fallon is a Design lecturer, Level-6 Co-Ordinator, and School Marketing & Recruitment Lead for the Institute of Jewellery, Fashion & Textiles, at Birmingham City University. Dean’s experience and interests intertwine art and design practices with research interests closely associated to his current role; spanning inclusive pedagogical frameworks in design, to practice led studies in culture, materials, and archival research. Recently Dean led a high-profile sustainability project with the global fashion brand Superdry.

Michelle Wetherell is currently a Fashion Design lecturer and School Academic Lead for the Institute of Jewellery, Fashion & Textiles, at Birmingham City University. She graduated from a Master’s degree in Fashion from Central Saint Martins in 2013. Since then, she has worked as a fashion practitioner with a focus on menswear, outerwear, and denim. Michelle started working in higher education alongside her practice bringing industry experience into the classroom. Her experience and interests focus on art and design practices, youth culture, heritage, and materiality with research interests in inclusive pedagogical frameworks, student centred learning, mattering and archival research.

References

Akalin, A. and Sezal, I. (2009) The Importance of Conceptual and Concrete Modelling in Architectural Design Education. The International Journal of Art & Design Education, Vol. 28 (1).

Busby, E. (2019) One in eight schools do not have library and poorer children more likely to miss out, study finds. Independent, 16 October, Available at: https://www.independent.co.uk/news/education/education-news/school-library-reading-poorer-children-books-funding-cuts-austerity-study-a9158601.html [Accessed 9 July 2022].

Carlson, D & Dobson,T. (2020) Fostering Empathy through an Inclusive Pedagogy for Career Creatives. The international journal of art & design education 39(2), pp. 430–444.

Chen, W. (2016) Exploring the learning problems and resource usage of undergraduate industrial design students in design studio courses. Int J Technol Des Educ, Vol. 26, pp. 461–487.

Collins, M. A. & Amabile, T. M. (1999) Motivation and Creativity. In R.J. Sternberg (Ed.) Handbook of Creativity. Cambridge University Press, New York, p. 298.

Darts, D (2004) Visual Culture Jam: Art, Pedagogy, and Creative Resistance, Studies in Art Education, 45 (4), p. 319.

Dineen, R. & Collins, E. (2005) Killing the goose: conflicts between pedagogy and politics in the delivery of a creative education, Journal of Art & Design Education, Vol. 24 (1), pp. 43–51.

Dong, Y. & Zhu, S. (2021) Gender differences in creative design education: analysis of individual creativity and artefact perception in the first‑year design studio. International Journal of Technology and Design Education.

Eyles A., Gibbons S., Montebruno P. (2020). COVID-19 school shutdowns: What will they do to our children’s education? CEP COVID-19 analysis (001). London School of Economics and Political Science.

Flett, G., Khan, A. & Su, C. (2019). Mattering and Psychological Well-being in College and University Students: Review and Recommendations for Campus-Based Initiatives. Int J Ment Health Addiction. Vol 17, pp. 667–680.

Flood, A. (2019) Britain has closed almost 800 libraries since 2010, figures show, The Guardian, 6 December, Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/dec/06/britain-has-closed-almost-800-libraries-since-2010-figures-show [Accessed 9 July 2022].

Gale, T. Mills, C. & Cross, R. (2017) Socially Inclusive Teaching: Belief, Design, Actions as Pedogogic Work. Journal of Teaching Education, 68(3), pp. 345-356.

Julier, G. et al. eds. (2019) Design Culture : Objects and Approaches. USA: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Kalkhurst, D. (2018). Engaging Gen Z students and learners. Pearson Education, 12 March, Available at: https://www.pearsoned.com/engaging-gen-z-students [Accessed 18 September 2022].

Lupo, E. Giunta, E. & Trocchianesi, T. (2011) Design Research and Cultural Heritage: Activating the Value of Cultural Assets as Open-ended Knowledge Systems. Design Principles and Practices: An International Journal, 5(6), pp. 432-450.

Moore, K. Jones, C., & Frazier, R.S. (2017). Engineering Education For Generation Z. American Journal of Engineering Education, 8 (2), pp. 111-125.

Orr, S. Yorke, M. & Blair, B. (2014) The Answer Is Brought About from Within You: A Student-Centred Perspective on Pedagogy in Art and Design.” The international journal of art & design education 33 (1), pp. 32–45.

Pajares, F (2001) Toward a Positive Psychology of Academic Motivation, The Journal of Educational Research, Vol 95:1, pp. 27-35.

Pilay, L. & Neves, M. (2020). A City’s Cultural Heritage Communication Through Design. Perspective on Design : Research, Education and Practice, Springer International Publishing AG.

Pownall, M. Harris, R & Blundell-Birtill, P (2021). Supporting student during the transition to university in COVID-19: Five key considerations and recommendations for educators, Sage Journals Vol 21,available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/14757257211032486#bibr28-14757257211032486 [Accessed 12 September 2022].

Raaper, R. and Brown, C. (2020), “The Covid-19 pandemic and the dissolution of the university campus: implications for student support practice”, Journal of Professional Capital and Community, Vol. 5 No. 3/4, pp. 343-349.

Ramsey, E. Brown, D. (2018). Feeling like a fraud: Helping students renegotiate their academic identities. College & Undergraduate Libraries, Vol. 25(1), pp. 86–90.

Raymond, M. (2010) The Trend Forecasterś Handbook. Laurence King Pub.

Ritchens, P. (1994) Does knowledge really help? CAD Research at the Martin Centre, in G. Carra &Y.E Kalay [Eds] Knowledge Based Computer Aided Architectural Design. London: Elsevier.

Shatto, B. and Erwin, K. (2016) Moving on From Millennials: Preparing for Generation Z. The journal of Continuing Education in Nursing, 47(6), pp.253-254.

Smith, S. Priestley, J. Morgan, M. Ettenfield, L & Pickford, R. (2022) Entry to University at a Time of COVID 19: How Using a Pre-arrival Academic Questionnaire Informed Support for New First year Students at Leeds Beckett University. All Ireland Journal of Higher Education. 14(2), pp. 9-12.

Stillman, D. & Stillman, J. (2017). Gen Z work: How the next generation is transforming the workplace. New York: Harper Business.

Sullivan, G. (1992). Human development, education (and economics): how life imitates art: twelfth annual Leon Jackman Memorial Lecture. Australian Art Education, 16(1), pp.4–16.

Tangney, S. (2014). Student-centred learning: a humanist perspective, Teaching in Higher Education, 19(3), pp. 266-275.

White, T. (2019). The 6Rs: Inclusive Creative Methodology for Design Research. The international journal of art & design education 38 (4), pp. 798–808.

Xu, Q, Liu, H. & Wu, S. (2021). Innovative Design of Intangible Cultural Heritage Elements in

Fashion Design Based on Interactive Evolutionary Computation. Mathematical Problems in Engineering.