Documenting a Gentle Resistance

Andrew Wilson

Practice Project: 100 People A Portrait of Co-Existence

Introduction

Introduction

For several years I have been working as an artist in a small residential neighbourhood called Shieldfield. Over the last three years this work has been directed through the lens of a portrait-film and community archive project called 100 People. The aim of this work has been to articulate a collective, incomplete, and interwoven narrative which reflects the rich and complex relationships of co- existence and solidarity in the neighbourhood.

The 100 People project emerges in direct response to Rebecca Solnit’s observation that the we are not very good at telling stories about a hundred people doing things and that “positive social change results mostly from connecting more deeply to people around us rather than rising above them.”[1]

As the artistic lead on the 100 People project, this paper is an attempt to clarify and contextualise the collective tendencies I have witnessed in Shieldfield within a broader framework of resistance, to identify the need for a more collective approach to storytelling.

Shieldfield Today

If you were in the city centre of Newcastle upon Tyne and you were to walk directly east you would soon find yourself in a small residential neighbourhood called Shieldfield.

Once a largely green area of farming and horticulture, Shieldfield was transformed

by industry into a bustling neighbourhood of housing, pubs, and shops. In the mid-late 20th century, via a slum clearance programme,[2] much of the terraced housing was demolished to make way for high-rise tower blocks, and more recently the area has seen an explosion in purpose-built and privately-owned student flats.[3]

Today, like many urban areas in the UK, Shieldfield is home to an increasingly complicated mix of people, diverse in cultural background, social status, nationality, faith, sexual orientation, and lived experience. A community-led strategic plan for the neighbourhood, published in 2022, identified the demographic of Shieldfield as:

“a multi-cultural area with around 5,000 inhabitants. It is intergenerational in makeup, and home to many new and young families, students, and older residents. Shieldfield also hosts housing for refugees and asylum seekers.”[4]

Within this social mix, the last eight years or so has seen a notable number of initiatives emerge. Led by residents and/or locally based organisations these initiatives share the broad aim to meet the range of emergent needs in the neighbourhood. These initiatives include:

- A volunteer run community cafe[5] with reliable opening hours, cups of tea at affordable prices, a friendly welcome, and a programme of events for cross-cultural celebration.

- An open and accessible community garden[6] where skills and knowledge are shared to grow fruits, vegetables, herbs, and flowers for collective joy and consumption.

- A free-to-access youth programme[7] providing space, resources, and support for the social and creative development of the many young people in the neighbourhood.

- A community co-operative[8] which provides a democratic framework for people of all ages and backgrounds to actively participate in their community, be it town planning solutions, knowledge sharing, or regular social events.

- An annual community football tournament,[9] co-organised by residents and organisations, encouraging participation regardless of age, gender, or ability to co-create a festival of mutual care and collective joy.

- A regular and free-to-access hot meal and community larder,[10] as a form of active solidarity, run by a nearby co-operative cinema, gig venue and café.

- A committed team of people who provide a wash, dry, fold and delivery, laundry service for elderly and disabled people living in the area.[11]

- A small contemporary art gallery[12] which runs workshops for young people and prioritises space within their public programme to exhibit their work, developing confidence, skills, and fun social interactions.

I could go on…

In a political and media landscape which repeatedly alerts us to the dangerous or self-seeking ‘other,’ these acts of solidarity demonstrated in Shieldfield may seem extraordinary, if not radical, given the increasing levels of precarity and individualism we are living through. Yet, I am hesitant to use the term ‘radical’ because as we witnessed throughout the Covid-19 pandemic, these collective tendencies have so often been our response to crisis. Amidst the unfolding of Covid-19 wide-ranging instances of kindness and solidarity were being reported from people reaching out to their neighbours by singing from their balcony,[13] to the formation of solidarity groups such as Food & Solidarity[14] in Newcastle (UK) or Adopt a Grandparent,[15] which started in Surrey (UK) and spread worldwide.

The exceptional circumstances of the pandemic encouraged new mutual aid groups to emerge, but it also made visible the kindness and solidarity that had already existed, as Rebecca Solnit observes in a collection of essays entitled Pandemic Solidarity, “they are indeed everywhere and always have been … they are what sustains us.”[16]

If we acknowledge that positive social action can result from connecting to people around us, from collective rather than solo action, how then might this be reflected in the stories we tell?

Methodology

Beginning in March 2022 with several introduction events, the 100 People project invited residents, workers, and social inhabitants of the area to co-design an ethical framework for the project. This involved several conversations and workshops to identify procedures for consent, a protocol for recording the audio/visual material, and considering the collective ownership of the recordings once completed.

Regarding consent, we acknowledged that different people have different levels of need, so we ensured information was shared in three distinct ways: written (a detailed information form), audio-visual (an animated storyboard about the project) and verbal (a one-to-one conversation).

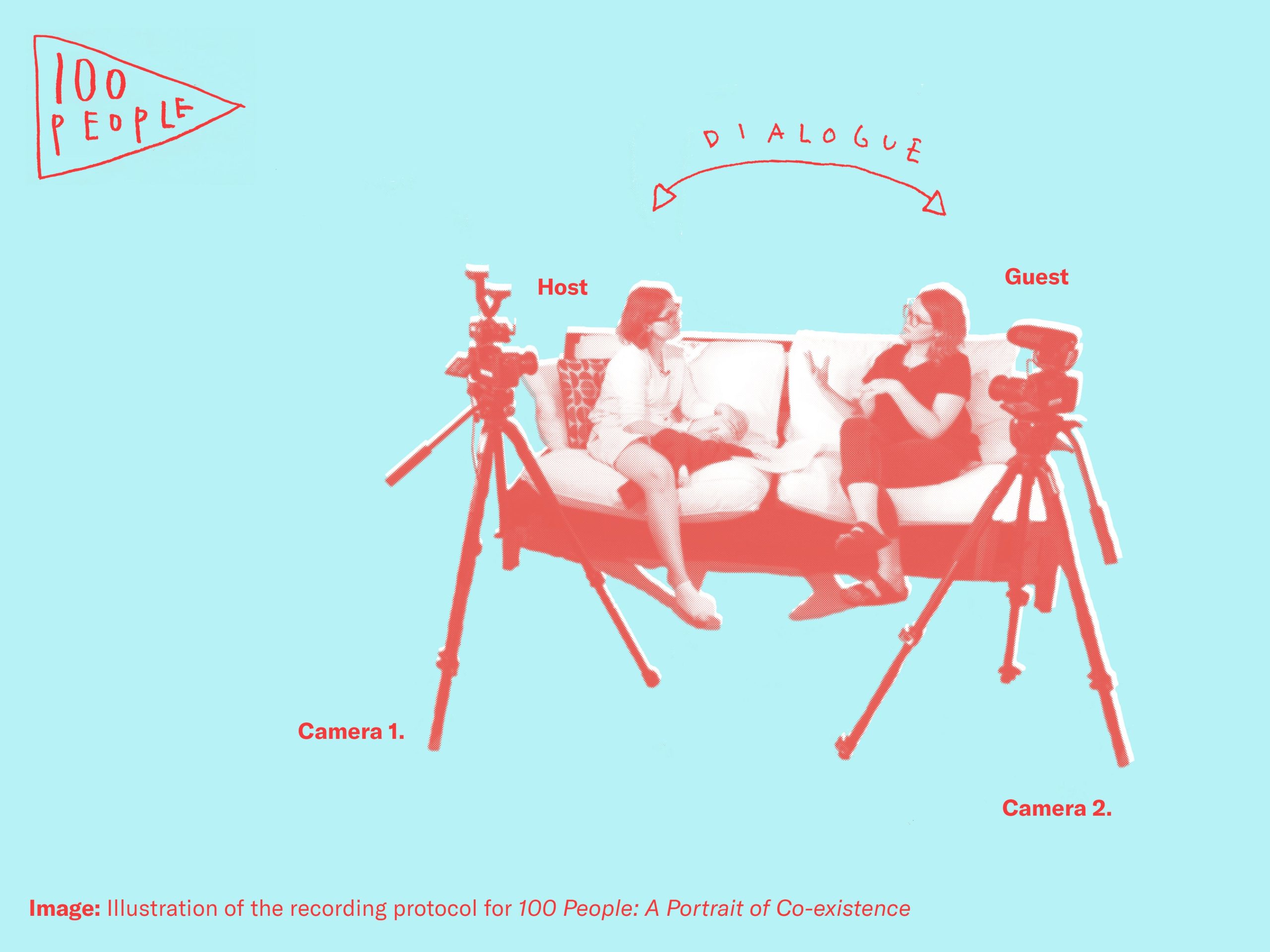

For recording we co-created a protocol which welcomed a conversation, rather than the usual interview format. If you identified as someone who either lives, works, or plays in the neighbourhood then you (the host) were encouraged to invite someone of your choosing (the guest) to have a recorded conversation with. This might be someone you know well, someone you have met only in passing, or perhaps someone you will be meeting for the very first time.

Before arranging a date for recording we ensured any access barriers were identified, such as language, mobility, child-care, or anything else that might limit someone’s ability to join in. Each recording took place at a venue and time of day of the host’s choosing, and lasted between one to two hours.

The recorded footage was then compiled and edited to form a feature film, 100 People: A Portrait of Co-Existence,[17] which has been screened to multiple audiences from both a cinema and gallery setting. Following initial screenings feedback from audiences include:

“It made me think about my own connection to the community, and my role in shaping it.”[18]

“Shows the beauty of solidarity beyond and despite the progressive destruction of our social infrastructures.”[19]

“Made me consider what it means to be part of a community and think about the differing needs of different groups, and how easy it is to only think of ourselves.”[20]

“It gave me an insight into the changing nature of communities and how it’s imperative to give local people a strong voice in any development. It seemed to me that relationship is key.”[21]

Once completed, all the raw unedited recordings were handed over into the collective custody of the community co-operative Dwellbeing Shieldfield.[22] The idea was to develop a digital archive that would be in common ownership, meaning the recorded conversations could continue to serve the community, long in the future.

A Gripping Tale

As I write, I am made aware of an article recently published in The Chronicle, Newcastle’s primary online and in-print news source. What follows is likely the inevitable consequence of the demise of local journalism rather than the fault of the journalist per-se.

Titled – I visited a district in the east of Newcastle which has the heart of a real community[23] the piece attempts to offer insight into Shieldfield via three different sources: a director of a local business, a local resident, and a local councillor.

Whilst highlighting the specific strategy of the business, the isolated opinion of the resident, and the ‘privilege’ of the local councillor to represent this neighbourhood, the article fails to name any common effort between the ordinary people or organisations at the ‘heart’ of the ‘community.’

Whereas the article nods to the community garden project, it fails to mention the youth programme, the community cafe, the dedication of the workers in the community launderette, and so much more. We are informed that ‘community’ exists, but we are given no insight into the organisational aims, nor the complex relationships that make it possible. Instead, we are left with the voices and faces of the business director and the local politician as guiding the story.

In her 1986 essay The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction, Ursula K. Le Guin recognises our tendency for the lone-hero narrative. Acknowledging that despite most of what we humans ate, in pre-historic times, was gathered (mostly by women) it was the hunter – the action hero of the day – that dominated our most captive stories:

“It’s hard to tell a really gripping tale of how I rested a wild-oat seed from its husk, and then another, and then another, and then another, and then another.”[24]

A woman, or several women, gathering grain might not make for the most heroic or dramatic story, much like the several phone calls, meetings, and online documents behind a community-led activity in Shieldfield say. But, if we are interested the representation of complicated co-ordination, perhaps we ought to imagine more compelling strategies.

The form of storytelling demonstrated within The Chronicle is significant not because the specific projects I mention are missing, but because the complex coordination, personal sacrifice, and collective agency demonstrated by these projects and the many people behind them are absent, therefore blunting the political potency of these collective actions.

Wider Resonance

Factors such as financial insecurity,[25] declining mental/physical health,[26] racialised scapegoating,[27] and a widespread feeling of political impotence has created a high-risk situation for social and economic deprivation in neighbourhoods like Shieldfield.

In her book The Old is Dying and the New Cannot Be Born,[28] social philosopher and critical theorist Nancy Fraser argues that a “dramatic weakening if not a simple breakdown of the established political classes” has created a gap for new forms of politics to emerge.

At first glance, from scrolling our phones or reading the news, it may seem that this gap is being dominated by a surge in extremist right-wing ideology, be it patriarchal misogyny, nationalist flag waving, multiple forms of racism, or by widespread conspiracy movements such as QAnon, Anti-vaxers, or Covid-19 deniers. But, if we look closer to home, we may find different stories, much gentler stories, of ordinary people demonstrating the political potency of a society based on solidarity, mutual aid, and what Lynne Segal has named ‘radical happiness.’[29]

In a public conversation I was part of in 2021, discussing how political ideas are being contested online and how these interactions intersect with our lives and relationships offline, film-maker Elaine Drainville stated:

“The next revolution we will experience will come about by beating paths to our neighbour’s door.”[30]

Drainville, as part of the film production team at Amber Collective during the mining strikes of the early 1980’s, had made several films alongside the mining communities and their industrial action. These films, called Trigger Tapes, were produced quickly, and distributed widely to share knowledge and encourage discussion at a time of significant difficulty within these communities. Although ultimately unsuccessful in preventing the closure of the pits, these mining communities were able to fight back against the political pressures they faced because they collectively got their act together.

On the ground, the situation faced today in neighbourhoods such as Shieldfield is vastly different to that of the mining strikes; unlike the pit villages of the 1980’s most people living in neighbourhoods like Shieldfield have vastly different relationships to work, leisure, and domestic life. But many of the tactics being deployed, namely solidarity and collectivism, could be regarded as being remarkably similar.

In Shieldfield it is not industrial action that is bringing the community together, but the vast variety of paths that are being beaten to each other’s door.

This then begs the question, how might we resist the barrage of content landing on our phones and TVs, and attempt to articulate stories that better represent the complex networks of peer-support and solidarity that surround us? As artist and film-maker Andrea Luka Zimmernan observes:

“We cannot make history by ourselves, we have to have all these different voices, and a multiplicity of voices to make history really alive.”[31]

Any attempt to articulate a story about the many people actively engaged in this activity, diverse in age, ethnicity, gender, faith, social and economic status, sexual orientation, viewpoint, background, language, and lived experience, will of course be a complex and messy task. For all the activity in neighbourhoods like Shieldfield there will be no singular spokesperson, no figurehead, no hero, and as such they are difficult narratives to tell.

But what if we tried?

[1] Solnit, R (2019) When the Hero is the Problem. Lit Hub. Article available at https://lithub.com/rebecca-solnit-when-the-hero-is-the-problem/

[2] Carmichael, I (2012) The demolition of housing and the destruction of communities: Shieldfield in Newcastle in the 1950s (Part of Breaking up communities? The social impact of housing demolition in the late twentieth century). The University of York. Article available at https://www.york.ac.uk/media/chp/documents/2012/BREAKING%20UP%20COMMUNITIES%20REPORT%20-%202ND%20NOVEMBER%202012.pdf

[3] Whetstone, D (2019), The amount of student housing in Newcastle once again in the spotlight, The Chronicle. Article available at https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/whats-on/arts-culture-news/amount-student-housing-newcastle-once-16390840

[4] Dwellbeing Shieldfield and Harper Perry (2022), Shieldfield: A Strategic Plan. Dwellbeing Shieldfield, Newcastle. Document available at https://www.dwellbeingshieldfield.org.uk/urban-development/strategic-plan

[5] The Shieldfield Forum Café, Shieldfield. Further information available at https://www.facebook.com/p/Shieldfield-Forum-Cafe-100064965602749/

[6] Shieldfield Grows, a partnership between Shieldfield Art Works and Dwellbeing Shieldfield. Further information available at https://www.saw-newcastle.org/shieldfield-grows/

[7] The Shieldfield Youth Programme, a partnership between The NewBridge Project and Dwellbeing Shieldfield. Further information available at https://thenewbridgeproject.com/events/shieldfield-youth-programme/

[8] Dwellbeing Shieldfield, Shieldfield. Further information available at https://www.dwellbeingshieldfield.org.uk/

[9] The Shieldfield Community Cup, Shieldfield. Further information available at https://www.starandshadow.org.uk/programme/event/5th-shieldfield-community-cup,7069/

[10] Community Kitchen, Star & Shadow Cinema, Shieldfield. Further information available at https://www.starandshadow.org.uk/programme/event/community-kitchen,6429/

[11] Shieldfield Community Launderette, Caring Hands, Shieldfield. Further information available at https://www.caringhandscharity.org.uk/general-8

[12] Slug Club, Slug Town, Shieldfield. Further information available at https://slugtown.co.uk/exhibition/slugclub-pop-up-exhibition-february-2023/

[13] Thorpe, V (2020), Balcony singing in solidarity spreads across Italy during lockdown, The Guardian. Article available at https://www.theguardian.com/world/2020/mar/14/solidarity-balcony-singing-spreads-across-italy-during-lockdown

[14] Food & Solidarity, Newcastle upon Tyne (UK), Further information available at https://foodandsolidarity.org/

[15] Mathers, M (2020), Coronavirus: 28,000 virtual volunteers ‘adopt a grandparent’ to help care home residents during lockdown, The Independent. Article available at https://www.independent.co.uk/life-style/health-and-families/health-news/coronavirus-lockdown-virtual-volunteers-adopt-grandparent-carehome-self-isolation-mental-health-a9442181.html

[16] Solnit, R (2020) Pandemic Solidarity. London: Pluto Press.

[17] 100 People: A Portrait of Coexistence (feature film) directed by Andrew Wilson. UK, 2023. 93mins.

[18] Checci, M (2023), from responses to a feedback form created by Shieldfield Art Works following the premiere screenings of 100 People a Portrait of Co-Existence.

[19] Checci, M (2023), from responses to a feedback form created by Shieldfield Art Works following the premiere screenings of 100 People a Portrait of Co-Existence.

[20] Bevan, K (2023) from responses to a feedback form created by Shieldfield Art Works following the premiere screenings of 100 People a Portrait of Co-Existence.

[21] Wylie, R (2023) from responses to a feedback form created by Shieldfield Art Works following the premiere screenings of 100 People a Portrait of Co-Existence.

[22] Dwellbeing Shieldfield, Newcastle upon Tyne. Further information available at https://www.dwellbeingshieldfield.org.uk/

[23] Younger, O (2024) I visited a district in the east of Newcastle which has ‘the heart of a real community’, The Chronicle. Article available at https://www.chroniclelive.co.uk/news/north-east-news/visited-district-east-newcastle-the-28559861

[24] Le Guin, U (1988), The Carrier Bag Theory of Fiction. First published in Women of Vision, Edited by Denise Du Pont, St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

[25] Thomas, T (2024), Areas of England with poorest health have higher rates of poverty, report finds. The Guardian. Article available at https://www.theguardian.com/society/2024/jan/18/areas-of-england-with-poorest-health-have-higher-rates-of-poverty-report-finds#:~:text=The%20analysis%20of%20ONS%20statistics,to%20be%20in%20poor%20health.

[26] Public Health England (2019), Better-mental-health-jsna-toolkit. Report available at https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/better-mental-health-jsna-toolkit/2-understanding-place

[27] Booth, R (2023), More than a million living in pockets of hidden poverty in England, says study. The Guardian. Article available at https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/dec/11/more-than-a-million-living-in-pockets-of-hidden-poverty-in-england-says-study

[28] Fraser, N (2019), The Old is Dying and the New Cannot Be Born. New York, Verso.

[29] Segal, L (2017), Radical Happiness, Moments of Collective Joy. London, Verso.

[30] Drainville, E (2021) post-screening conversation between Elaine Drainville, Mwenza Blell, Lindsay Duncanson, Andrew Wilson, and Dawn Felicia Knox, following This Trust Idea (film short) directed by Andrew Wilson, as part of Collective Now, at SIDE Cinema, Newcastle upon Tyne, June 2021. Video available at https://vimeo.com/565666465

[31] Luka Zimmerman, A (2020), Unexpected Views: Andrea Luka Zimmerman on Caravaggio. The National Gallery. Video available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TGsHPAD-n-U

Links:

- 100 People: A Portrait of Co-existence (2023), trailer for feature film: https://vimeo.com/890308499

- 100 People, project website: https://www.100peopleshieldfield.org/

- Andrew Wilson, artist website: https://www.iamandrewwilson.co.uk/

100 People is an arts project developed in partnership with Shieldfield Art Works, Dwellbeing Shieldfield and artist Andrew Wilson.

To date 100 People has received financial support from Shieldfield Art Works, Newcastle University Engagement and Place Fund, and Arts Council England.

The project has received additional support from many individuals, groups, and organisations including; Caring Hands Charity, Christ Church Shieldfield, The Forum Café, Fugitive Images, The NewBridge Project, North-East Film Archive, and The Star and Shadow Cinema.

Beginning in March 2022 with a period of action research events that included workshops and screenings, 100 People has produced an exhibition (A Community of Objects), a feature film (100 People: A Portrait of Co-Existence), and a community archive (still in production).

The film, 100 People: A Portrait of Co-Existence, adopted an unorthodox approach of split-screen one-to-one conversations as an alternative to the customary interview style. All the raw unedited recordings are in the collective custody of the community co-operative Dwellbeing Shieldfield, comprising a collectively owned digital archive.

About the author

Andrew Wilson (b.1982, he/him) is an artist based in Newcastle upon Tyne UK. Working both individually and in collaboration with many other artists, individuals, groups and organisations Andrews work results in slow, invested, and thoughtful projects. Andrew is a studio holder at The NewBridge Project, a steward for the community co-operative Dwellbeing Shieldfield, and a member of West End Housing Co-op.