Breath Awareness for Dancers in Higher Education: Somatic Practice as an Alternative Approach to Movement Education

Maisie Beth James

Royal Birmingham Conservatoire, Birmingham City University, B4 7XR, England

Email: Maisie.James@mail.bcu.ac.uk

ORCID iD: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3187-4136

Download the PDF of this article

ISSN 2752-3861

Abstract

Previous research into dance education has highlighted the problematic effects that traditional dance technique classes can have on undergraduate students within higher education (Roche, 2016; Brodie and Lobel, 2004; Allen, 2009). As a practitioner and researcher, I have investigated throughout my postgraduate study whether somatic practice can be adopted as a supplementary or alternative approach to movement education. Drawing on reflections shared by undergraduate university students, I position somatic practices as a more expressive, nurturing way of approaching movement that differs from technical training within dance education. Somatic methods within dance education directly draws attention to the inner experience of the body, rather than dwelling on the external, often objectifying perspective of the Self and the Other within traditional contemporary dance technique. This idea forefronts a positive understanding of the body where the well-being of the dancer is central to the movement experience, rooted in self-regulation and self-expressivity. The research found that leading weekly somatic workshops provided dance students with somatic principles to draw upon and utilise in their curriculum-based technique classes. As this research was conducted with students who were taking part in technique classes frequently, findings uncovered that students adopted the somatic principle of breath awareness in their technique classes to enrich their movement opportunities, improve their general well-being, and approach movement more attentively. So, applying this research directly to the traditional dance context explicitly using qualitative methods to conduct research, I underpin breath awareness (Brodie and Lobel, 2004) as a key theme and principle that sits alternatively to traditional contemporary technique. In relation to somatic literature and my experiences as a somatic facilitator, I deem somatic practices as an alternative approach to moving and being that challenges specific dominant discourses and culturally informed practices within traditional higher education dance technique.

Context of Research

Somatic practice can be defined in many different ways of gaining an awareness of the body through movement. Emphasis on the human being experienced by himself (or herself) from the inside encompasses the practice (Hanna, 2004) whilst establishing a compassionate relationship with Self that nurtures self-development and expression (James, 2020). As suggested by Batson (2009), somatic practices can also be referred to as “body therapies, bodywork, body-mind integration, body-mind disciplines, movement awareness, and movement (re) education” (Batson, 2009, p. 2). The emphasis on body-mind connectedness is therefore at the forefront of somatics, offering an opportunity to explore integration through movement. With the deep-rooted philosophy of somatics responding to Cartesian dualism from the 19th century, the idea of the mind-body split aroused a need for a different approach to movement and further provoked a revolt where the human condition and movement education was concerned (Batson, 2009).

As I aim to generate awareness of somatic practice as an alternative modality to education, my experiences have therefore influenced the concepts explored throughout this article. Findings from this investigation positioned somatic practice as a supplementary, alternative way of learning for dancers where practice is a means for creative expression. As I have been frequently involved in traditional dance technique classes both as a participant and facilitator, this article presents participant reflection and engagement as findings in relation to my own reflective perspectives. In this sense, this inquiry would therefore not exist without the interest in my own experiences and relationships within the technical dance environment that explicitly contrasts with my expressive, gratifying experiences within somatic movement practices. As an implicit outcome of the research, I aimed to raise awareness of somatics as an explorative practice that enhances the human experience and promotes the self as central to education (James, 2020).

In 2019 I conducted a research project with undergraduate dance students attending University. On a weekly basis I facilitated somatic workshops informed by somatic practitioners who have already integrated somatic practices into the higher education setting (Brodie and Lobel, 2004; Allen, 2009; Alexander and Kampe, 2017; Glaser, 2015). With the primary focus exploring how the somatic principle of breath awareness can support dance students, emphasis was given to the felt experience of moving and how breath awareness can promote movement possibilities for dancers in their technique classes (Brodie, 2004; James and Stockman, 2020). Although critical in its application to the higher education setting, writing surrounding somatic facilitation was fundamental in ensuring that I provided the appropriate environment for the students to feel comfortable and supported whilst attending to their bodies in the studio. Whilst I did not integrate somatic principles into a technique class myself, I provided somatics as an alternative practice that challenged higher education technique for students.

As a practice researcher and facilitator, I introduced new somatic intentions and concepts into practice that the students were not necessarily aware of prior to the investigation. Although the students were involved in somatic classes as part of their curriculum-based dance training, students had not experienced in depth explorations of breath awareness, interoceptive processes, or engaging with their environment, which forefronts somatics in practice. The undergraduate students involved in the investigation ranged from the ages of nineteen to twenty-four with different background experiences within dance practice. Some specialised in Commercial, Street, Contemporary and Jazz dance, so angling the research from a somatic perspective was a new learning experience for all. This was significant to the outcome of the research as I endeavoured to gain authentic reflections of the lived experience reflexively no matter previous movement experience. I was then able to apply my own understandings of somatic literature and ideologies from already existing practitioners and theorists within the field.

As this research project positioned the students as central to the outcome, it was important to invite students who were willing to take part in all workshops on a weekly basis. Six students volunteered to take part in the research, providing a small group to focus on throughout the process. I invited students to complete their own reflective process journals as a way of recounting their experiences from each workshop so they could carry the lived experience into their technique classes held directly after my somatic sessions.

Breath and Movement Quality

In many forms of dance, the use of breath as support is not necessarily viewed as an integral aspect of the moving body (Romita and Romita, 2016). As a result, little time is given for dancers to explore the use of breath and how it can support their movement in the moment, which further arouses concerns with regards to artistry and expressivity within the higher education setting (Romita and Romita, 2016). As the awareness of how breath moves throughout the body is a central principle within the somatic field, it is important to recognise the individual, embodied experience as an outcome of using breath awareness for a creative process (Williamson, 2009). I therefore propose somatics as an individual experience that originates from the Self and supports spontaneous, expressive movement differing from technique classes (Dryburgh, 2018).

Moreover, as the functionality of breath invites the participant to experience a range of embodied responses, internal sensations and an awareness of how breath moves through the body, new awarenesses of the Self are present within the studio space. Conrad (2007) argues that breath awareness enlivens our creativity and conscious relationship with the self (Conrad, 2007). For example, the awareness of the diaphragm when involved in a somatic movement meditation awakens a certain impulsive response to the body in the moment. As we engage with imagery of the diaphragm, lungs, and the chest filling with oxygen, we encourage a lived understanding of internal bodily functions and how these functions can translate into movement responses (Feldenkrais, 1990). Somatic processes therefore foster a positive, integrated relationship with the mind and body, thus rejecting the mind-body dichotomy often expressed through traditional technique and Cartesian philosophy (Detlefsen, 2013).

With reference to Image 1, exploration of the body through hands on touch is also at the core of somatic approaches and is often used to engage with our sense perception. We can begin to tune into our bodily sensations (Williamson, 2020). Here, I gently place my hand on the students cervical spine to invite a sense of softening and awareness of that specific area. Often, movement may occur as a response to touch, promoting slow and considered movement.

In relation to the movement quality of a dancer, as already suggested, the self-expressive, authentic nature of somatic practice both enhances and encourages an exploration of different movement patterns that a dancer may not normally engage with when it comes to technique class (Romita and Romita, 2016). The awareness of breath when moving can also be expressed as “a meeting place for the conscious and unconscious control of movement” (Brodie, 2012, p. 39). This directly refers to habitual movement patterning that dancers often engage with when operating in technique classes. As breath awareness is such a useful and significant in road to self-expressive qualities of movement, the dancer can then begin to engage with an increased awareness of their habitual ways of moving. Due to the authentic, improvisational nature of somatic practice, the dancer is invited to respond to the body as a stimulus for movement, no matter its appearance or aesthetics. Rather than relying on habitual motifs or phrases taught and performed in traditional technique classes, the dancer can respond to the body’s impulses in the moment in tune with their well-being, self-regulating the body (James, 2020; Williamson, 2020).

Within curriculum-based technique classes specifically, I acknowledge that students are able to explore the use of breath in enhancing their movement, however, it has been revealed that this experience is limited to group improvisations (Melton, 2012). As the use of breath encourages awareness of the dancer’s centre, they are then able to develop a sense of being grounded in class, so their movement that follows can therefore be supported through this sense of grounding and gravity (Hawkins, 1991). Freeing an individual to explore this sensation in direct response to somatic processes gives permission for the dancer to take risks beyond the limitations of the studio environment. Hawkins (1991) suggests, “this feeling of security makes it possible to interact with more openness and respond with more spontaneity” (Hawkins, 1991, p. 103).

Methodology

Green and Stinson (1999) stipulate the postpositivist worldview as offering a more subjective approach to attaining data, characteristically using qualitative methods of data collection. Due to the differing motivations, perspectives and individual philosophical viewpoints of the students, the postpositivist approach and worldview was therefore a suitable method in which the data from this project is framed. As I also applied my own reflective journal and perspectives to the primary data, the intentions of the project were unpacked subjectively and relative to the viewpoints of others involved in the process. Seeing that somatic practice holds subjectivity at its core with an emphasis on engaging individuals in an explorative, experiential setting, it was paramount that I gathered the data subjectively as well as approaching the practical focus of the project from a subjective, impartial place. The process thus aligned with the evolving somatic intentions. In this sense, Green (2015) outlines that developing theory about certain research processes is about allowing questions and ideas to emerge throughout. Due to the emergent, organic nature of somatic practices, the project was process-driven rather than focusing on goal-orientation that is explicitly evident within technical dance training.

Furthermore, the subjective nature of the project adopted an understanding of personal experiences and perspectives to forefront the emergent findings. As the postpositivist paradigm suggests that researchers view inquiry logically (Creswell, 2014), I resonated with postpositivism in my methods and approaches to the project whilst understanding that the outcome was dependent on gaining perspectives from the students as primary data. I was also influenced by deconstructivist thinking as a way of challenging dominant discourses within dance education. The somatic workshops provided an opportunity to go beyond universally ingrained practices where movement is concerned and develop a sense of discovery in the studio. Deconstructivism reflects postmodern thought as a framework of understanding alternative ideologies to challenge already idealised assumptions. Whilst I did not frame this project within a postmodern framework specifically, I offer somatic practice as an alternative discourse to higher education dance technique situated within traditional higher education. I also offer the suggestion that somatic practice may compliment traditional technique by providing the body connectedness that technique seems to lack within the higher education setting (Green, 2002). Relying solely on the findings collected from the students and literature, I deem the practical focus of this project at its core.

In terms of structuring the practice within the project, it was important that I was open to adaptability and maintained clear intentions for the students to build on themselves. This further invited collaborative input from the students in shaping the process. Reflective journaling, video documentation, focus groups, a pilot study, and questionnaires were the qualitative methods used to collect data throughout the experiential process. Directly addressing Giguere (2012), I also kept a self-reflective journal throughout to maintain integrity, reliability, and to engage in criticality of the process. As it was paramount to receive ethical approval to work with undergraduate students within a university setting, a research proposal was submitted accompanied with all documentation and questions that were aimed for the students. This investigation therefore aligned with university policy, ethical procedures and encompassed a scope of practice that is used throughout the somatic field of scholarship.

Practice Research in the Somatic Context

As a central part of my qualitative project, I conducted six somatic workshops that focused on certain somatic principles in order to gain perspectives from the undergraduate dance students. Mainly utilising the methods of focus groups, reflective journaling, and self-reflection throughout, I was able to align my own subjective outlooks of the process in line with the students who regularly took part in curriculum-based technique classes. Practical inquiry coupled with a theoretical understanding of somatics as a movement modality informed my workshop practice and the intentions of the project. Fundamental to the process was engaging the students in creativity, self-expression, and the desire to move, rather than fitting a certain description evident within technique class (Romita and Romita, 2016). It was therefore imperative that I provided an encouraging environment that nurtured the Self through compassion, understanding and encouraging a sense of autonomy.

Smith and Dean (2014), Kershaw (2009) and McKenchie and Stevens (2009) write extensively about practice research within the dance and moving context, drawing upon fundamental approaches to gaining research. As practice research is deemed as a provisional term for research in the arts, it directly positions the researcher central to their own practice both as a practitioner and researcher (Smith and Dean, 2014). Research and practice therefore became intertwined throughout (Nimkulrat, 2007). As my project relied on workshop facilitation, the practice research approach corresponded with the emergent aims of the project where emphasis was given to the emerging perspectives of the students involved. I consider the transformative influence of the primary data conducted to have motivated the process.

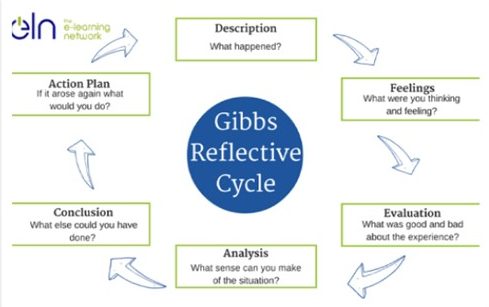

Reflective Journaling

An integral aspect of the research process was reflective practice. Informed by Gibb’s reflective model (2011) as outlined below, students reflected on their lived experience of each somatic workshop to relate their experiences to their technique classes. This ultimately provided the opportunity for the students to draw clear conclusions, parallels, or differences in how their bodies reacted to somatically informed workshops and technique classes (Dryburgh, 2018). Although Zeichner and Liston (1996) advocate a more critical method of reflection, Gibb’s reflective cycle (2011) (as seen in Figure 1) supported the nature and intention of the project, centralising experiential reflective practice. As this model emphasises ‘thinking’ and ‘feeling’ as key phases for the students to consider, reflecting in this manner can be interrelated with the somatic intention of noticing and tuning into the internal experiences of how the students felt in the moment. By combining both thinking and feeling, the idea of embodied knowledge can be evident in my research findings due to the connection between mind-body integration and the engagement with personal narratives (Pakes, 2003; Williamson, 2020).

By engaging with reflective practice in a somatic environment, students were invited to reflect on themselves creatively and spontaneously in the moment. This expressive intention gave permission for the students to experience their bodies as a whole (James, 2020). This of course invited openness and expressivity of the body and emotions. Each week, the students completed a reflective journal to document their lived experience of the sessions, providing an insight into authentic, embodied reflections that contributed to my understanding of how somatics can be considered as an alternative practice to technique class. Reflective practice was thus essential in providing an in-road to my facilitation, helping me to understand the lived expectations of the students. The collaborative, co-creative process ultimately allowed content and experience to emerge in line with the Self and Other.

Imagery, Movement and Expression

As the functionality and awareness of breath supports movement quality and is deemed vital for a dancer (Conrad, 2007), it was important to consider whether the use of imagery also supported the students experiences. Generally, at the start of each somatic workshop I invited the students into a process of engaging with their breath patterns, rhythms, and how the movement of breath throughout the body stimulated minimal or expansive movement. For the students, this was an opportunity to tune into their bodies and use the function of breath to open up authentic, spontaneous movement possibilities. According to Brodie and Lobel (2004), breath is regarded as a founding principle rooted in somatic practices such as Feldenkrais, Alexander Technique, Skinner Release Technique and Body Mind Centering. Whilst holding a vital role in enabling dancers to let go of habitual movement patterning, impulses that are inherent in the body can come into expression (Brodie and Lobel, 2004). Breath awareness is therefore profound in stimulating movement possibilities and generating an awareness of the body as a whole (Brodie and Lobel, 2004). Additionally, as somatic practice is historically focused on breath eliciting change within the body “it functions under both voluntary and involuntary control” (Brodie, 2012, p. 40). This showcases the conscious and unconscious functioning of breath within our bodies that can be utilised in creative movement practices.

Here, I simply place a hand on the students diaphragm to sense into their body. Students often feedback how they then become aware of their breathing patterns, and how the use of the diaphragm enhances the movement of breath. This simple exercise can be used at the start of a session to encourage a relationship between breath and body, inviting students to consider their bodies in a simplistic yet integrated way.

Specifically, the second somatic workshop invited students into an interoceptive process that focused on the movement of breath throughout the body. This process was informed by Brodie and Lobel (2004) in order to investigate whether the intention of the process led to an understanding or experience of somatics being alternative to their technique classes. As suggested by somatic practitioners and theorists working within the field (Eddy, 2009; Conrad, 2007; Brodie, 2012; Williamson, 2014, 2016), it is significant for dancers to gain an awareness of their breath in its applications to technical training. There is a profound conception of somatic methods as alternative in its intentions, outcomes and learning approaches to traditional, technical training (Brodie and Lobel, 2004; Roche, 2016). Emphasis is also given to dissolving bodily tension through the flow of breath, and was key imagery that students found beneficial in my somatic workshops. As I built on Brodie and Lobel’s (2004) processes throughout the somatic workshops, it was imperative for me as a facilitator to stay true to the processes in order to evaluate how alternative somatics was in its applications to technique practices. I did however deviate from the processes to allow time and space for students to alter their positions and bring their conscious awareness back to their bodies at different times of the processes. I felt it was important for students to have a sense of autonomy to tune into their bodies organically.

Romita and Romita (2016) provide a relevant explanation of why dance students should be aware of their relationship with breath when involved in practices within a technical setting. As the muscular support for breathing can help a student to discover necessary internal functioning of the body, breath can further help and support the body when moving (Romita and Romita, 2016). By maintaining an awareness of how breath functions within the body, a mechanism for aiding movement possibilities can be cultivated. Referring to my somatic workshops specifically, students frequently articulated an embodied experience of moving that centred their bodies in relationship with self-expression. When it came to technique classes, students fed back that a profound lack of breath awareness was evident, resulting in a disembodied experience of moving. The body was therefore presented objectively rather than experienced subjectively. This is often communicated in somatic literature and provides an innate difference in intention between traditional technique classes and somatic practices (Roche, 2016). In particular, students also mentioned how they did not breathe in technique classes due to concentration on performing movement correctly and in time with fellow dance students. As time keeping and performance are not representative of somatic practices, there was a distinct difference in intention for the students who were introduced to expressive, slow-paced principles. Here lies a clear, alternate purpose of somatic practices.

Moreover, as maintaining breath awareness is central to somatic experiencing, students noticed how their movement reflected their breathing patterns. Within the technical setting, an emphasis lies on the aesthetics of movement rather than the experience of the body (James and Stockman, 2020), so it was enlightening for students to engage in movement for the sake of moving and connecting with their bodies spontaneously. Students shared,

“I did not used to breathe in technique class. I used to wait until the end and then breathe in between the exercises. I feel now that I am trying to breathe into movement more” (Participant one, 2019).

Here, it is evident that participant one engaged with a new experience when it came to breath awareness and movement. Being able to breathe into movement enabled students to experience their movement from a somatic, expansive perspective, where movement was initiated from their bodies. As breath awareness encourages students to understand an embodied experience, somatics cultivates an inner learning that is not always evident in technical training (Brodie and Lobel, 2004). Here lies another example of the alternativity of somatic practices. Synthesising this directly with Brodie and Lobel (2004), breath for the students was a founding principle that retrospectively invited somatic integration with movement and breath.

Tension

An idea widely discussed within somatic education and literature is how breath exercises and processes can make the participant feel relaxed and connected to their body in the moment (Alexander and Kampe, 2017; Allen, 2009; Eddy, 2009; Glaser, 2015). However, a key finding that surfaced throughout the project was how body tension became apparent when the students took part in Brodie and Lobel’s (2004) breath process. All students expressed in their reflective journals that the breath process was disjointed and hard to follow, resulting in their minds wandering and a lack of focus on the body at times. Students reflected that they could feel where they were holding tension in each position of the exercise and tried to use breath to “work through” and “dissolve” the present tension (Participant three, 2019). Although the students fed back that they felt relaxed and rested for the majority of the experience, emphasis on tension and stiffness was communicated in their reflective journals. This ultimately suggests that whilst the process encouraged engagement with internal sensations and the students were connected with their whole bodies in the moment, frequent moments of tension resulted in a partially disengaged experience. This is an emergent finding from the project that differs from somatic literature. I also acknowledge that when an individual is tuning into their bodies attentively through somatic processes, awareness differs, wandering to different parts of the body at different times.

Although there are clear distinctions between somatic practices and technique classes, there was an interesting finding that seemed to draw parallels between the two. Students involved in the project declared in their reflective journals feeling disconnected with their bodies due to the rigid nature of the breath process facilitated in one of the somatic workshops. As somatic practice encompasses the Self as central to the learning experience (James and Stockman, 2020), it was a surprise to comprehend participant reflections that did not relate to the intention of somatic practices. With students communicating a difficulty in applying breath awareness to their embodied experience when it came to the sensation of tension, it was a different experience than having the freedom of movement initiated by breath awareness. Participant two stated ‘I felt disconnected from my breath, and I was too focused on where I was moving next’ (Participant two, 2019). Likewise, students also identified that “we were going from a really relaxed position to downward facing dog, which meant that all the blood was rushing into your head” (Participant four, 2019). Unlike somatic literature that suggests breath processes encourage an embodied connection with the self, focusing on the experience of movement (Eddy, 2009; Alexander and Kampe, 2017; Williamson, 2016), Brodie and Lobel’s breath exercise (2004) did not allow the students to fully focus on themselves in the moment. As the researcher, I question whether the positions and movement included in Brodie and Lobel’s (2004) breath process were distracting for the students. The dynamic shifts included seemed to promote a disembodied connection with Self. I argue that due to the exercise being too instructional and lacking a sense of autonomy, students were a little restless and unable to engage with their bodies fully. Movements involved shifting from the fetal position to downward facing dog, which perhaps alludes to the intention of less is more within somatic pedagogy (Williamson, 2016). Though the students may not have experienced the breath process as authentically in the moment, when it came to movement quality, students noticed a shift in their embodied experience. I question whether students would have benefitted more with slower movement focusing on one part of the body at a time during this early stage of somatic experiencing.

Conversely, findings from the project also indicated that students were able to move expressively, organically, and in relationship with their bodily impulses. A mind-body integration occurred where movement connects “the mind and body in the most immediate fashion” (Brodie and Lobel, 2004:82). This was evident in both participant reflection and in video documentation of the somatic workshops that translated the authentic, spontaneous movement experience. Presented by Bell (2019) is the significance of how somatic practices can create an awareness of the body and Self where it has previously been lacking (Bell, 2019). As technique classes seem to promote the appearance of the body in performance rather than the felt experience of somatics (Dryburgh, 2018), it is no surprise that students fed back how they felt their bodies were whole throughout the somatic workshops. I therefore suggest that dancers can greatly benefit from somatic pedagogy as a different/alternative modality of movement that enhances well-being and mind-body integration.

Additionally, students also communicated how important it was for them as training dancers to become more involved with somatic practices and breath awareness. In line with the student’s grading criteria for their undergraduate dance assessments, students advised that they were expected to demonstrate how they applied breath awareness to their movement in assessment and technique class. As the researcher, I argue that without an understanding of breath as a foundational principle to movement, students are unable to transfer their embodied awareness and experience to their technical assessments. Breath awareness in the technical context, according to Participant three refers to, “the functioning of breath that enhances the presentation of movement” (Participant three, 2019). For example, if a dancer is to perform a certain routine or motif for an audience, it would be expected that the movement is finished properly, and bodily lines are correct. According to participants, issues of breath awareness within the technical dance setting seem to arouse a lack of self-expression and creativity that further limits the movement that is carried out. Certain strict or regimented movement simply does not allow for breath awareness or for breath to become a stimulus for moving. A question arises as to how students navigate through traditional technique classes without having an awareness of their own breathing or their bodies in the moment. It would therefore seem pertinent to use a framework of somatic practices to inform a dancer’s movement for their examinations. Although breath awareness is perceived as different in technique class and somatic practices within this project, somatic principles could be used to support dancers in their technique classes. The explicit distinction in approaches that somatics offers and what technique class imposes are thus alternative in its intentions.

Dance Discourses: A Conforming Practice

As previously suggested, having an awareness of breath can enhance a dancer’s movement both in technique class and somatic practice, however, the movement experience in technique class and somatics is profoundly different for the individual. Romita and Romita (2016) suggest that the experience of movement in a technical setting can be limiting in individualism and its applications to movement opportunities. Movement is therefore reliant on dominant practices such as mimic-based learning and set material rather than exploring movement through initiation from the body. No longer does the individual experience an organic connection with the internal sensations of breath, but dancers somewhat use breath as a means to push through movement (Romita and Romita, 2016). Instead of engaging and exploring how breath and body awareness can enhance movement possibilities, students are seemingly conditioned to employ ideals put in place by lecturers (Green, 2002). Due to fast paced, aesthetically pleasing movement being expected of dance students in technique class, dancers cannot always engage in a connection with their bodies in the moment (Green, 2002). What interested me as a researcher was observing dance technique classes taught by university lecturers and trying to understand what principles and intentions drive the technical setting. Repetitive, fast paced teaching methods and exercises were adopted to assert certain disciplines over students. It seemed to me that the students engaged in an inability to connect with their bodies or expressivity in the dance space. After all, dance should be a creative practice that allows the Self to come into expression (James and Stockman, 2020). I therefore claim this lack of body and breath awareness to be a problematic underpinning of technique class due to the lack of organic, embodied experience and minimal creativity and self-expression often promoted by dancers. With the emphasis on performance and the aesthetic values of movement being vital in technique class, the compassionate, cultivating experience of the body is therefore lost (Romita and Romita, 2016).

Furthermore, after exploring the anatomical functioning of breath in more detail during the somatic workshops, students mentioned being able to explore movement more freely. As the breath awareness processes allowed dancers to explore where their movement was originating from in their bodies, students were aware of initiating movement from both the body and from breath (Brodie and Lobel, 2004). Accordingly, in somatic movement, “the role of the breath in connecting to the core and in finding the flow of movement is emphasised” (Brodie and Lobel, 2004:82). Students therefore engaged in a whole new awareness with the freedom to move, further allowing an exploration of the body to take place in a nurturing environment that promoted a positive relationship with the Self and movement. Due to the students having a conscious awareness of how breath stimulated their movement, students affirmed that somatic intervention and principles informing the research project improved their well-being and relationship with Self.

Cultivation of sensory awareness within somatic pedagogy can result in free-flowing, genuine movement originating from the body, which gave students the opportunity and autonomy to carry out movement from their own accord, independently and freely in the moment. This is echoed by Allen (2009) who suggests that somatic movement education can support a dancer both in training and technique by identifying the body as an end in itself rather than an instrument of perception (Allen, 2009). This on the other hand is where an awareness of movement can come into play for an individual who understands their body and can engage in movement exploratively. The felt sense and sense perception are therefore foundational in an embodied movement experience.

Students also commented “the main thing that I have been able to take from this experience is breath awareness and I am actually breathing through the exercises now” (Participant five, 2019). On a practical level for the students, the use of breath meant that their movement felt more expansive and indulgent both spontaneously through improvisation and with set material. By understanding their own relationships with their bodies and its functions, the somatically informed workshops utilised breath as integral. Awareness of internal sensations (interoception) were also fundamental experiences students made connections with to further utilise and enhance their lived experience of movement. Due to the workshops centralising somatic teaching methods, collaborative learning, and the promotion of nurturing/cultivating awareness, principles of embodied listening was therefore paramount (Bell, 2019).

Again, the use of touch can be used to enhance an integrated understanding of the body. It is important to switch roles when facilitating somatics due to the reciprocal relationships that practice encompasses. Here, the student is simply placing her hands on my right shoulder and upper arm to invite a sense of softening and space within this area of the body. By having the eyes closed, I was able to tune into this area and notice sensation through my interoceptive awareness.

Future Considerations and Conclusions

This article has highlighted the significance of breath awareness and somatics as an alternative movement practice to dance technique class. By centralising the use of breath as central to practice in somatic workshops, a subjective understanding of the relationship between the body, self, and the environment has emerged for me as a researcher and the students who participated in the project. For the purposes of this investigation, students were invited into somatic processes leading into movement invitations that encouraged the body to explore its impulses. As this project provided an in-depth exploration of how somatic principles are intentionally different to technical practices, findings concluded how beneficial the use of breath and self-awareness became a dominant understanding throughout the process.

As a development of this project, observations of more traditional technique classes will be of great importance if conducting a lengthier project to evoke more questions surrounding dominant discourses implicit of technique class. Subsequently, a succeeding development of this research would be to offer the integration of somatic practice within higher education technique class that builds on somatic principles to develop movement possibilities and self-expression. As I have offered additional somatic workshops for dance students to experience in this project, the opportunity arose for students to explore movement, well-being, the body, and the Self in a nurturing environment that sits alternatively to dance technique class. Successive research could position the integration of somatic classes as curriculum-based education, however, there is much more research and scepticism regarding the lived, transformative experience of individuals involved with somatics and if this can translate into the educative environment. Further research could also explore somatics in more depth using different methodologies to engage in the embodied/felt experience and relationship between the post-cartesian perception of the mind-body. By further adopting Brodie and Lobel’s previous research as a stimulus for this project, I was able to make my own assumptions based on already trialled concepts and principles.

Although it is clear that this project has contributed to the understanding of breath awareness and somatic practices as alternative ways in approaching movement, my own interpretations of the process have influenced the conclusions reached. An opportunity for further research in this area that continues to question technique class is required within professional training and higher education. I deem this project in offering additional insights and experiences for dance students to adopt into their own creative practice. The student lived experience was therefore central to this project. Different somatic principles can be adopted to achieve similar projects; however, this research acts as a baseline for future development in showcasing somatics as an alternative movement practice.

About the author

Currently studying her PhD at Birmingham City University looking into somatic practice and pain management, Maisie completed her BA at The University of Winchester in Education Studies and her MA at Liverpool John Moores University in Dance Practices. Throughout her academic studies, Maisie has synthesised philosophies of the body, somatic practices, and practice research to inspire her current inquiries into pain management. Since graduating, she has been involved in various research projects with dance students and research participants investigating the applications of somatic practice as a therapeutic modality and alternative, experiential approach to movement education. As Associate Editor for the Journal of Dance, Movement and Spiritualities, Maisie positions herself at the forefront of emergent knowledge within the field of somatic movement. Her practice research approaches coupled with her theoretical understandings of the field informs her attitudes towards the Bio-Somatic Dance Movement Naturotherapy course she is also studying at Moving Soma.

References

Alexander, K. and Kampe, T. (2017) ‘Bodily undoing: Somatics as practices of critique’, Journal of Dance and Somatic Practice, 9(1), pp. 3-12, doi: 10.1386/jdsp.9.1.3_2

Allen, J. (2009) ‘Written in the body: reflections on encounters with somatic practices in postgraduate dance training’, Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices, 1(2), pp. 215-224, doi: 10.1386/jdsp.1.2.215_1

Arnold, P. J. (2005) ‘Somaesthetics, education, and the art of dance’, Journal of Aesthetic Education, 39(1), pp. 48-64, https://www.jstor.org/stable/3527349

Barbour, K. (2011) Dancing Across the Page: Narrative and Embodied ways of knowing. Bristol: Intellect.

Barr, S. (2009) ‘Examining the technique class: re-examining feedback’, Research in Dance Education, 10(1), pp. 33-45, doi: 10.1080/14647890802697189

Batson, G., Quin, E. and Wilson, M. (2011) ‘Integrating Somatics and Science’, Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices, 3(1+2), pp. 183-193, doi: 10.1386/jdsp.3.1-2.183_1

Batson, G. and Wilson, M. (2014) ‘Training attention- the somatic learning environment’, In Body and Mind in motion: dance and neuroscience in conversation. Bristol UK: Intellect Ltd, pp. 129-137

Bell, A. (2019) Somatic Mindfulness: What Is My Body Telling Me? (And Should I Listen?). Available at: https://www.goodtherapy.org/blog/somatic-mindfulness-what-is-my-body-telling-me-and-should-i-listen-0619185

Bolton, G. (2014) Reflective Practice: Writing and Professional Development. London: SAGE Publications Ltd.

Butterworth, J. (2004) ‘Teaching choreography in higher education: a process continuum model’, Research in Dance Education, 5(1), pp. 45-67, doi: 10.1080/1464789042000190870

Brodie, J and Lobel, E. (2004) ‘Integrating fundamental principles underlying somatic practices into the dance technique class’, Journal of Dance Education, 4(3), pp. 80-87, doi: 10.1080/15290824.2004.10387263

Brodie, J and Lobel, E. (2006) ‘Somatics in dance- dance in somatics’, Journal of Dance Education, 6(3), pp. 69-71, doi: 10.1080/15290824.2006.10387317

Brodie, J. (2012) Dance and Somatics: Mind-Body Principles of Teaching and Performance. United States: McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers.

Burby, L. (2004) ‘Mind your body: Feldenkrais: when it feels good, it is good: dancers find the practice helps with pain’. Dance Magazine. Available at: https://www.thefreelibrary.com/Mind+your+body%3A+Feldenkrais%3A+when+it+feels+good%2C+it+is+good%3A+dancers…-a0114740820

Bryman, A. (2012) Social Research Methods. New York: Oxford University Press Inc.

Carter, C. (2000) ‘Improvisation in Dance’, The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, 58(2), pp. 181-190, https://www.jstor.org/stable/432097

Conrad, E. (2007) Life on Land. California: North Atlantic Books.

Creswell, J and Miller, D. (2000) ‘Determining Validity in Qualitative Inquiry’, Theory Into Practice, 39(3), pp. 124-130, doi: 10.1207/s15430421tip3903_2

Creswell, J. W. (2009) Research design: Qualitative, quantitative, and mixed methods approaches (4th ed.) London: Sage Publications, Inc.

Detlefsen, K. (2013) Descartes’ Meditations: A Critical Guide. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Dryburgh, J. (2018) ‘Unsettling materials: Lively tensions in learning through ‘set materials’ in the dance technique class’, Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices, 10(1), pp. 35-50, doi: 10.1386/jdsp.10.1.35_1

Eddy, M. (2009) ‘A brief history of somatic practices and dance: historical development of the field of somatic education and its relationship to dance’, Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices, 1(1), pp. 5-27, doi: 10.1386/jdsp.1.1.5_1

Fortin, S. (2017) ‘Looking for blind spots in somatics’ evolving pathways’, Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices, 9(2), pp. 145-155, doi: 10.1386/jdsp.9.2.145_1

Fraleigh, S. (1987) Dance and the Lived Body: A Descriptive Aesthetics. University of Pittsburgh Press: United States.

Fraleigh, S. (1998) A vulnerable glance: Seeing dance through phenomenology. In Carter, A (ed.) The Routledge Dance Studies Reader. London: Routledge, pp. 135-143.

Fraleigh, S. (2017) ‘Back to the dance itself: In three acts’, Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices, 9(1), pp. 235-252, doi: 10.1386/jdsp.9.2.235_1

Giguere, M. (2012) ‘Self-Reflective Journaling: A Tool for Assessment’, Journal of Dance Education, 12(3), pp. 99-103, doi: 10.1080/15290824.2012.701168

Glaser, L. (2015) ‘Reflections on somatic learning processes in higher education: Student experiences and teacher interpretations of Experiential Anatomy into Contemporary Dance’, Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices, 7(1), pp.43-61, doi: 10.1386/jdsp.7.1.43_1

Green, J. (1999) ‘Somatic authority and the myth of the ideal body in dance education’, Dance Research Journal, 31(2), pp. 80 -100, doi: 10.2307/1478333

Green, J. and Stinson, W. (1999) Postpositivist research in Dance in Researching Dance: Evolving Modes of Inquiry. London: Dance Books, pp. 91-123.

Green, J (2002) ‘Foucault and the training of docile bodies in dance education’, Arts and Education, 19(1), pp. 99-126, https://www.researchgate.net/publication/276266649_Foucault_and_the_training_of_docile_bodies_in_dance_eductaion

Green, J. (2015) ‘Somatic sensitivity and reflexivity as validity tools in qualitative research’, Research in Dance Education, 16(1), pp. 67-79, doi: 10.1080/14647893.2014.971234

Hanna, T. (2004) Somatics: Reawakening the Mind’s Control of Movement, Flexibility, And Health. California: Da Capo Press.

Hartley, L. (2005) Embodying the Sense of Self. In: Totton, N (ed.) New Dimensions in Body Psychotherapy. Maidenhead: Open University Press, pp. 128-142.

James, M. and Stockman, C. (2020) ‘Sartre and somatics for the Pedagogy of movement in contemporary dance’, Journal of Dance, Movement and Spiritualities, 6(1&2), pp. 119-131, doi: 10.1386/dmas_00006_1

James, M. (2020) ‘Self-regulation and the subjective Self: Practice to cultivate awareness’, Journal of Dance, Movement and Spiritualities, 7(1&2), pp. 105-118, doi: 10.1386/dmas_00019_1

Kershaw, B. (2009) Practice as Research through Performance. In Hazel, S and Dean, R (eds.) Practice-led Research, Research-led Practice in the Creative Arts. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 105-125.

McKenchie, S. and Stevens, C. (2009) Knowledge Unspoken: Contemporary Dance and the cycle of Practice-led Research, Basic and Applied Research, and Research-led Practice. In Smith, H and Dean, R (eds.) Practice-led Research, Research-led Practice in the Creative Arts. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 84-104.

Melton, J. (2012) ‘Dancers on Breathing- from interviews and Other Conversations’, New Zealand Association of Teachers and Singers. Available at: http://www.joanmelton.com/sites/default/files/pdf/Dancers%20on%20Breathing%20.pdf

Nimkulrat, N. (2007) ‘The Role of Documentation in Practice-Led Research’, Journal of Research Practice, 3(1), http://jrp.icaap.org/index.php/jrp/article/view/58/83

Olsen, A. (2002) Body and Earth: An Experiential Guide. USA: Middlebury College Press

Press, M. (1983) ‘Anxiety and the Dance Class’, Design for Arts in Education, 84(6), pp. 21-23, doi: 10.1080/07320973.1983.9940712

Pakes, A. (2003) ‘Original Embodied Knowledge: the epistemology of the new in dance practice as research’, Research in Dance Education, 4(2), pp. 127-149, doi: 10.1080/1464789032000130354

Roche, J. (2016) ‘Shifting embodied perspectives in dance teaching’, Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices, 8(2), pp. 143-156, doi: 10.1386/jdsp.8.2.143_1

Romita, N and Romita, A. (2016) ‘Breath: the gateway to expressivity in movement’. Available at: https://blog.oup.com/2016/08/breathing-dance-theater/

Rumson, R. (2015) The E Learning Network [online image]. Available at: http://resources.eln.io/gibbs-reflective-cycle-model-1988/

Smith, H and Dean, R. (2009) Practice-Led Research, Research- Led Practice. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Williamson, A. (2009) ‘Formative support and connection: Somatic movement dance education in community and client practice’, Journal of Dance and Somatic Practices, 1(1), pp. 29-45, doi: 10.1386/jdsp.1.1.29_1

Williamson, A. (2016) ‘Reflections on phenomenology, spirituality, dance and movement-based somatics’, Journal of Dance and Somatic Practice, 8(2), pp. 275-301, doi: 10.1386/jdsp.8.2.275_1

Williamson, A. (2020) ‘Post-Newtonian anatomy and physiology: The gravitational and parasympathetic experience in bio-somatic dance movement naturotherapy’, Journal of Dance, Movement and Spiritualities, 6(1&2), pp. 171-198, doi: 10.1386/dmas_00009_1