Entrepreneurial ‘Insta-Drag’: An Analysis of Nottingham Based Drag Performers’ Social Media Profiles

Zack Ditch

PhD Researcher, School of Arts and Humanities, Nottingham Trent University, NG11 8NS, England

Email: zack.ditch2020@my.ntu.ac.uk

Download the PDF of this article

ISSN 2752-3861

Abstract

Drag has proven to be a subject of particular interest in the fields of gender and queer studies, with recent debates exploring the neoliberalisation, globalisation, and deradicalization of the art form. This is usually attributed to the success of the reality TV show RuPaul’s Drag Race and further research identifies that neoliberal notions of self-branding and competition have infiltrated drag due to this reality tv phenomenon and the heightened visibility of drag. Yet, most of these studies explore drag in the United States, leaving a gap that fails to explore drag cultures in other national contexts, their relation to neoliberalism, and notions of drag-related entrepreneurialism to engage the creative industry. Where current literature exploring UK-based drag does exist, there is a heavy focus on metropolitan cities such as London, underrepresenting smaller regional queer communities in mid-sized cities, like Nottingham. Surprisingly, little work utilises Instagram as a valuable resource even though it provides drag performers a platform of self-expression, branding and competition in facilitating a networked access to images, posts, captions, bios, and engagement-rates of these queer communities. Analyses of drag performer Instagram profiles might then reflect and develop work surrounding the entrepreneurial attitudes of drag performers. This paper seeks to occupy these blindspots within drag-based research by using an alternative approach that engages with 20 Instagram Profiles of Nottingham-based drag performers through a triangulation of data analysis methods. This paper addresses how performers utilise Instagram to develop entrepreneurial self-branding in lesser-metropolitan areas and the role of location (or regionality) in drag performers’ expressions of neoliberal subjectivity, with considerations on their varying online ‘success’ and the factors that might influence this. This is a topical study, in a context where drag-visibility continuously increases (as with the recent RPDR UK) and queer academia is increasingly invested in the post-millennial mainstreaming of queer cultures.

Introduction

At the current moment, drag is a regular subject of research in several academic fields including gender, queer, media, and theatre studies. A central theme within these fields is the concept of neoliberalism and its inherent ties to drag performance in its newfound hypervisibility within popular culture, with some stating that ‘‘todays drag culture’’ has become ‘’celebrified, professionalised, commercially viable, brand-orientated and mainstream’’ whereby a ‘‘logic of individualism, competition and the market’’ has infiltrated the performance form and its enactors’ ideologically revised approach to the form (Feldman and Hakim, 2020, pp. 386-7). It should be noted that this operation of and succumbing to neoliberal ideologies are widely argued (Feldman and Hakim, 2020; Hall-Araujo, 2016) to be attributed to both the capitalist context in which western drag exists within, and to the legacy of RuPaul’s Drag Race. Another argued reason for this increased popularity – and associated conforming to and reliance on capitalist ideals/operations – is the ever-continuing development and engagement with social media which has ‘‘facilitated drag culture’s move from the fringes to mainstream’’ (Feldman and Hakim, 2020, p. 387). This provokes questions around how platforms like ‘’Instagram and YouTube have affected the ways that [drag] performers understand and perform themselves’’ (Feldman and Hakim, 2020, p. 386).

Instagram, a social media platform on which the sharing of image-based content is promoted, ‘‘is currently one of the most widely used [platforms] around the world’’ (Inan-Eroglu and Buyuktuncer, 2018, p. 941). As Quaan-Haase and Sloan observe, ‘’because of its proliferation in society […] social media provides new avenues for researchers across multiple disciplines’’ (2017, p. 14). Social media platforms offer an important and rich resource for publicly accessible data as ‘‘interactions and engagement on social media are often directly linked to […] events taking place outside of it’’ (Quaan-Haase and Sloan, 2017, p. 3), which is potentially even more important in a post-Covid 19 context. The role of social media has been heavily identified as having great importance in drag’s neoliberal function as evidenced in Lingel and Golub’s study on the drag community of Brooklyn (New York) and the sociotechnical practices enacted through Facebook (2015), alongside Feldman and Hakim’s work which identifies and explores the link between the ‘’celebrification of drag culture’’ and social media (2020). However, there is little to no research that explores the ways in which drag performers utilise platforms like Instagram to display the entrepreneurial attitudes that operate in neoliberal society. Research investigating drag-based social media engagement seems even more necessary as ‘’Instagram is currently the dominant platform for drag [performers]’’ in a context where ‘’an active social media presence is increasingly regarded as essential to the making of a contemporary drag career’’ (Feldman and Hakim, 2020, p. 394). Research that investigates Instagram (or other) social media profiles of certain populations is rare but does exist, as with a study by Inan-Eroglu and Buyukyuncer where images from dieticians’ posts are categorised and coded to explore how those demographics engage with the platform (2018). Other studies highlight the entreupenurial potential of online platforms for drag performers such as Lingel and Golub’s study on the drag community of Brooklyn, New York and their engagement with Facebook (2015). This kind of research does not seem to be prominent in the studies of queer cultures. This article seeks to bridge this gap by bringing together social-media research and the study of drag performance cultures exploring notions of neoliberalism and its inherent links to drag culture, whilst considering how the entrepreneurial attitudes of performers displayed through Instagram can highlight these explorations further. It should be noted that this study is part of a much larger doctoral project.

Methodology

The constructivist, mixed-method framework of this study offers originality in both the domain of drag-based research and in its specific focus on both qualitative image/content-based data and quasi-quantitative data. As such this method is similar but distinctive (in its focus on drag) from other social media-based studies such as those already mentioned (Inan-Eroglu and Buyuktuncer, 2018).

Data Collection

Two main methods of data collection have been conducted for this study. Initially, existing literature searches were undertaken to identify key arguments and explorations within this research domain than can be used to corroborate and interrogate key themes within the paper. Secondly, is the media search for Instagram profiles belonging to Nottingham-based drag performers. From these profiles the following were recorded, the most recent 10 posts of each profile (images, captions, comment sections), the number of others followed by the participant, the number of those following the participant, and the total number of posts by the participant). These were found unobtrusively through google searches using the key words: Drag, Drag Queen, Drag King, Drag Performer, Instagram and Nottingham. The selection criteria for participants seeks self-identified performers of drag who frequent, highlight and/or construct Nottingham’s drag scene through their profiles. The participants did not need to identify as of a particular gender. 20 suitable participants were selected, whose names have been anonymised and replaced with a corresponding number (e.g., 1). All data was collected in 4 hours to limit the potential change in datasets as accounts could grow and additional content could affect data. For image analysis, the most recent 10 posts from each profile were utilised – leading to a total number of 200 images/posts being analysed. These choices regarding timeframes and the selection-process were informed by the study with a similar methodology prior discussed by Inan-Eroglu and and Buyuktuncer’s (2018), however their much larger study utilised a greater number of participants (298) and so the number of posts engaged with was adapted to fit the smaller population size of this study. The ethical implications of all participant involvement and the needed considerations taken to protect all individuals are discussed later within this section.

Data Analysis

A triangulation of data analysis methods has been consisting of: i) text-based latent content analysis (on existing literature and captions, comments, and interactions profile posts), ii) image-based latent content analysis (images from profile posts), iii) quasi-quantitative analysis.

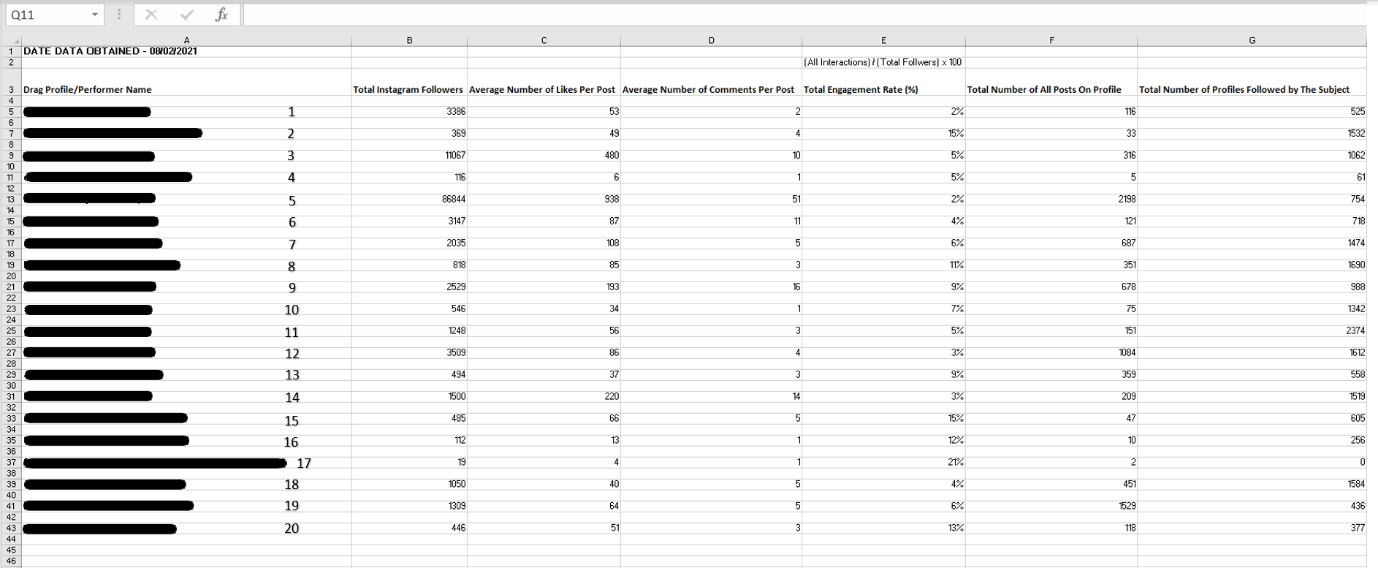

Where qualitative analysis methods intend to explore how drag performers utilise Instagram and how these utilisations might be deemed entrepreneurially charged, quasi-quantitative data analysis offers insight into how often these utilisations occur and give indications of what might lead to differing ‘success’ rates of performers therefore synthesising and corroborating qualitative data. This consisted of ‘supplementary counting’ of data such as performer total follower counts (Bryman, 2015, p. 631), and descriptive analysis where simple averages and calculations were made based on collected data e.g. the regularity of posts, how often certain trends occurred within the small population’s data, and the overall engagement rates of each participant (all posts/likes/comments divided by total followers). Following this, datasets were placed into Microsoft Excel spreadsheets. Secondly, qualitative text-based content analysis drew linguistic themes and formed subsequent discussion points from existing academic literature in addition to post captions and comment sections. Finally, qualitative image-based content analysis was used to seek trends, themes, and develop points of discussion based on the visual imagery displayed on the participant’s profiles (posts), as Instagram’s primary function is an image-sharing social media site.

Ethical Considerations

To eliminate the need for consent, this study focused specifically upon public Instagram profiles found through google searches using the keywords discussed earlier. Therefore, providing the necessary ethical conditioning to omit the need for informed consent from participants. I have however taken additional ethical considerations into account to safeguard all participants and their data further. Firstly, all data utilised from participants’ profiles is ‘‘extant data’’, meaning that the datasets are made from ‘existing materials developed without the researcher’s influence’ and where there is ‘’no direct contact with individual participants’’ (Salmons, 2017, p. 182). This kind of data includes ‘‘posts or exchanges of visual media’’ and ‘’text-based communication’’, all of which is data utilised (Salmons, 2017, p. 183). Consequently, research using this type of extant data ‘can be conducted without informed consent’ (Salmons, 2017, p. 185). All quotes in this article are also only partially written to aid anonymity. Finally, and potentially most importantly, all data (written and visual) will be anonymised and therefore no names or examples of images will be used in the final study.

Multiple sources were utilised in the grounding of ethical proceedings for the study, heavily using Driscoll and Greg’s work on the ‘’ethics of virtual ethnography’’, which illuminated the need to be ‘‘sympathetic’’ towards all participants included whilst not simply relying on ‘’notions of authority and discipline in academia’’ (2010, p. 19) resulting in the above ethical considerations made which appreciates the complex nature between researcher and online participant in online cultures.

Discussion/Findings

Data Analysis

All qualitative data, once collected and analysed as described above, has been synthesised into four main categories that relate to what I argue adheres to notions of entrepreneurial attitudes highlighted in drag performer Instagram profiles. These categories are: i) self-marketing and self-as-brand, ii) marketing of others, iii) marketing and showcasing personal talent, and iv) mixing of private and drag ’identities’.

Table 1: Primary Categories and Performers Exampling Them

|

Identified Primary Categories Related to Entrepreneurial Attitudes |

Performers Identified Who Have Displayed This in Some Form |

| Promotion of the Self-Brand | [All Performers] |

| Marketing of Others | 1, 8, 11, 12, 13 |

| Showcasing Personal Talent | [All Performers] |

| Mixing of Private and Drag ‘Identities’ | 5, 8, 9, 10, 12, 14 |

Whilst qualitative data analysis has been utilised to explore what entrepreneurial methods and neoliberal ideologies are enacted by drag performers through engagement with Instagram, considerations of quantitative data in the form of descriptive and simple quasi-quantitative analysis helps to suggest what methods performers use and how they use them, and how these determine their success. However, this is intentionally supplementary as to develop existing discussions and nuances around themes identified through qualitative methods. All quantitative datasets are listed below.

Some social media analysts argue that engagement rates are the most important metric in assessing success when analysing social media profiles (Ken, 2014). These rates are calculated through the following equation: [(All Comments, Likes, Shares) / (Total Followers) X 100] (Chacon, 2018). However, this is not fit for the purpose of the study. Those with the highest engagement rates in these datasets also have the lowest potential reach (due to having the lowest total followers), i.e. even lower than the potential reach of those with the lowest engagement rates. Therefore, for this study, the individual’s total follower count will be considered as the most prominent factor in assessing their success, as this is also considered by some social media analysts as an important metric (Jin et al, 2019).

Table 2: Forms of Drag Performers’ Lowest and Highest Engagement on Instagram

| Question | Lowest Engagement | Highest Engagement | Numerical Difference |

| Total Instagram Followers | 19

(Performer 17) |

86844

(Performer 5) |

86825 |

| Average Likes Per Post | 4

(Performer 17) |

938

(Performer 5) |

934 |

| Average Comments Per Post | 1

(Performers 4, 10, 16, 17) |

51

(Performer 5) |

50 |

| Total Engagement Rate | 2%

(Performer 1) |

21%

(Performer 17) |

19% |

Self as Brand

Self-branding is the process whereby individuals develop ‘’a distinctive public image for commercial gain and/or cultural capital’’ and additionally, where humans can become parallel to ‘‘commercially branded products’’ in their benefitting ‘’from having a […] public identity that is a unique selling point’’ or is ‘’singularly charismatic and responsive to the needs and interests of target audiences’’ (Khamis et al, 2017, p. 191). This first section will explore identified examples of self-branding and marketing enacted by drag performers through their Instagram posts and engagement with online audiences. This category reflects one of the more dominant datasets created as all performers were found to exemplify the utilisation of posts for building and sustaining self-brands associated with their drag personas.

The first subcategory is the explicit marketing of events showcasing the individual drag performer, exhibited by performers: 1, 10, 11, 12, and 16. All five performers had at least once posted advertisements for live events on their Instagram profile including posters for club nights/events as exampled by performer 1: ‘’Ultimate Drag Race Quiz, hosted by [their drag-name] […] at Bar No 27’’ where a ticket price of ‘’£5 entry’’ is required. Through these posts, performers engage with discussions around ideas of self-branding through marketing themselves as a potential attraction adding interest to a local venue in hopes of acquiring ticket sales, as self-branding situates itself as an ‘‘attention-getting device’’ to ‘’achieve competitive advantage in a crowded marketplace’’ (Khamis et al, 2017, p. 195) in this case for both the bar holding the event, and the performer. The performer attempts to engage in local Nottingham-based economies where their ‘‘capacity for commercial relevance sits within increasingly dominant economic realities’’ (Khamis et al, 2017, pp. 200-1) as venues compete for consumers and performers fight for recognition and visibility, especially since there are few venues that house drag in Nottingham. We might also presume that the performer here is economically benefitting from the event and their prior marketing of it, although events such as these are sites of low and unsustainable earnings for drag performers especially in lesser-metropolitan areas like Nottingham (Feldman and Hakim, 2020, p. 391).

The second subcategory is the advertisement and linking of branded consumerist product/companies within posts. Here, participants’ posts resonate particularly with debates and ideas around ‘’micro-celebrity’’, describing ‘’ordinary people’’ who might not be referred to as a celebrity who ‘’use social media to build fame’’ (Usher, 2020, p. 171) and influence on platforms like Instagram. Similar to the ways in which beauty influencers make obvious notation of products (and the creator company) that are used to create make-up focused pictures, performers 3, 5, and 14 listed relevant beauty products used in the make-up look they create and post: ‘’@makeupobsession X @tiffany Kaleidoscope Palette’’ under the subtitle ‘’Products:’’ (Performer 3). Johnston defines these types of posts as ‘’advertorials’’ which refers to the posting of ‘’branded content that fits into the influencer’s […] narrative’’ and sits ‘’effortlessly into their feeds’’ (2020, p. 510). Although there is no evidence that this post is sponsored by the brand themselves, it nevertheless promotes their product very much like a marketing campaign image that the brand themselves might create. This is a trend that occurs across Instagram and is enacted by several profiles through the layering of ‘’image, text and tags’’ relating to a brand’s purchasable products. Thus, the individual acts as a marketing advertisement for that product and seems to replicate the ‘‘aim of selling consumer goods’’ (Usher, 2020, p. 173). There are several potential benefits for the performer here, most prominently including the potential for the brand to repost the performers content to their company profile. This would increase the performer’s visibility and social media reach and potentially their following consequently, and transactionally the company can promote the reliability of their product through the performer’s content. An important potential transaction in a context where Instagram promotes the need for individuals to present themselves as marketable products within economies utilising both social currency (in likes, shares and comments) and economic currency (Marwick, 2015, p. 142) where perhaps opportunities for economic gain are limited (as in many mid-sized British cities such as Nottingham). It is most clearly articulated within these kinds of posts that ‘’the human brand’’ becomes ‘’synonymous with’’ corporate brands and ‘’hence with the product’’, helping to cement the importance of followings and high engagement on social platforms as ‘‘self-branding makes most sense’’ if influencers ‘‘lend their names profitably to major brands’’ (Khamis et al, 2017, p. 193). This focus on product-advertising also begins to play into problematic notions of money spent and quality of product correlating with the production of “good” drag and shows how ‘’platforms of self-expression’’ such as drag artistry ‘’become commodified’’ through self-marketing (Feldman and Hakim, 2020, p. 389). It should be noted here that the likelihood of being reposted and recognised by these brands is relatively low due to a ‘’media surplus’’ of similar drag and non-drag based content ‘‘where audiences are saturated with so much to choose from’’ (Khamis et al, 2017, p. 195).

Performer 9 replicated this type of post but shared an image of themselves wearing an LGBTQ+ Pride badge created by a small Nottingham-based independent company. Differing from other examples discussed, the product advertised could potentially highlight a social objective in alliance with LGBTQ+ awareness and promotes spending to be done within their local geographic economy, unlike huge corporate beauty brands. Here, performer 9 embodies ‘authenticity’, a trait commonly found to be desirable and appreciated in a micro-celebrity/influencer. Existing academic debates on authenticity and celebrity cultures illustrate that ‘’compelling narratives potentially attract audiences’’ for reasons such as being ‘inspirational’ and having a sense of relatability (Khamis et al, 2017, p. 196). Performer 9 conveys pride in their queer identity through donning and promoting the LGBTQ+ badge. By promoting it to audiences who are already following them (and much more likely to be interested in LGBTQ+ scene/culture as they already have an interest in drag), they focus advertising to appropriate audiences and heightens the chance of sales. The potential reliability for the performer by audiences is also established here as authenticity ‘‘becomes a commodifiable endeavour that galvanises the attention economy’’ and contributes to ‘‘a presentational culture that values the promotion of the self at its most accessible’’ (Johnston, 2020, p. 509). Drag is thus ‘‘transformed’’ into a space ‘‘of and for commercial enterprise’’ (Feldman and Hakim, 2020, p. 387). Marwick defines the attention economy as ‘’a marketing perspective assigning value according to something’s capacity to attract eyeballs in a media-saturated, information-rich world’’ and users like the performers discussed in this study use ‘‘them to increase their online popularity’’ (2015, p. 138).

Quantitative data analysis is also helpful to assess success within this category when considering the frequency of content posting. Performers 5 and 3 (those with the highest follower counts) have an average time between posting of 2-3 days, whereas performers 17 and 16 (those with the lowest follower counts) have an average time between 7-14 days of posting content on the platform. This suggests then that the regularity of posting is an important contributing factor to one’s success as a drag performer on social media, corroborating existing “advice” on online platforms: ‘’It’s generally recommended to post at least once per day […] on Instagram’’ with a bare minimum recommendation of ‘at least once a week’ (Myers, 2020). This begins to speak to notions of neoliberal tendencies already discussed as the success of self-branding is reliant on and sustained through ‘‘consistency, distinctiveness and value’’ (Khamis et al, 2017, p. 196) which regular and sustained content posting helps to achieve, as indicated through follower count.

Marketing of Others

A less visible and dominant category identified from qualitative data analysis is the marketing of other drag performers through participant profiles. Only five of the twenty performers exhibited forms of this. The most prominent subcategory highlights collaborations with other drag performers and/or collectives like in a post by performer 1 captioned ‘’POSE’’ also tags the profile of performer 18 who is pictured alongside them. All five examples of this (by five participants) were photos taken with other drag performers and provided information to access and find their collaborator. This helps to reaffirm discussions on the importance of ‘’community’’, which seems inherent to the practice and social importance of drag to performers (Knutson et al, 2018, p. 42), within the drag scene of Nottingham as in the example above where two performers share each other’s profile to their different audiences and therefore increase visibility. This shares similar properties with previously discussed notions of authenticity. Through evoking senses of community and even friendship, the participants could be interpreted to be ‘’performing authenticity and intimacy’’ to “heighten one’s status’’ (Johnston, 2020, p. 509), in order to widen reach and likeability as with discussions where the appeal of authenticity is deemed as liked by audiences. The collaboration between performers, in addition to creating positive images and notions around Nottingham’s drag scene, also allows for each participant to be seen by audiences that they would not necessarily have reached solely (due to having different followings). This collaboration technique is a ploy used by several influencers across the platform, and also between brands and influencers, as it allows for the development of followings and the engagement and reputation that comes with it.

A much less visible subcategory is the showcasing of upcoming events by other performers that do not include the participant themselves. Only performer 1 exhibited this when they shared a poster for the ex-RuPaul’s Drag Race star Trinity “the Tuck” Taylor who was to appear at “Pryzm Nottingham”. This elicits similar senses of community that seem so integral to the creation of the LGBTQ+ safe spaces in the spaces of art and cultural production, which appeals to queer audiences and therefore builds upon reputability for the performer. It should also be noted that when celebrating the future performance of an internationally renowned performer such as Trinity Taylor in the city of Nottingham, it helps to draw attention to the local scene as it imbues the city with a sense of ‘worth’, which may draw attention to Nottingham’s drag scene and perhaps even introduce larger audiences which would be beneficial for performers within that small community as it would most likely increase opportunities due to heightened demand for drag performance in the city. Linked to this is a smaller subcategory of performers who posted their in-drag meetings with RuPaul’s Drag Race stars where they are pictured alongside them in a professional setting (such as a live performance) as seen in three posts by performer 8 who is pictured beside three different international drag stars. This works towards enhancing the validity of the individual, highlighting that they are ‘worthy’ of performing alongside such reputable and “talented” performers, therefore establishing a “professionalised proforma for which the purpose is primarily the perpetuating of consumer culture” (Usher, 2020, p. 175).

Marketing and Showcasing Personal Talent

The third identified category, which encompasses examples from all 20 performers, is the marketing and showcasing of personal talent through Instagram. This category is arguably the richest regarding how many examples were identified, as over 90% of posts analysed for this study were used to explore and corroborate discussions in this section. The most common examples here are self-portraits of the drag performer, or as they are more commonly referred to as “selfies”: “an image that includes oneself” usually “for social media” (Merriam-Webster, 2021). Most of these images were relatively close to the face of the performer, with an apparent focus on the make-up work created by the individual, as with performer 3 who captioned a post: “another shot of this look but without all the fancy lighting so you can see the makeup better”. This can perhaps be viewed as a direct example of “identity construction” through “strategically inspired image control” which places “emphasis on the atomised, distinctive self” of the performer (Khamis et al, 2017, pp. 200-01). In focusing on these skills, and in creating a carefully and specifically curated emphasis on their make-up artistry and skill, the performer might attempt to aesthetically distinguish themselves and their content from similar content on Instagram, thus validating arguments that the “commercialisation of social media and users” has a direct effect on “motivations for participating and specific practices and forms of content generation” (Feldman and Hakim, 2020, p. 387). The performer attempts to justify their worthiness of recognition, which can be rewarded with social currency in online engagement with their impressive and aesthetic content which taps into appreciations for the beauty industry. When considering this alongside earlier discussions of branded posts it holds further resonance, as “Instagram is a platform that is based on visual aesthetics and filtered images, which makes it a suitable ecosystem for promoting beauty products” (Jin et al, 2019, p. 567). Therefore, reliance on impressive visual aesthetics and curated imagery like that of performer 3 matches with the promotional ecosystem of Instagram as a digital platform. The regularity of selfies across social media platforms like Instagram is also notable as they appear to be “omnipresent online” from all kinds of profiles (Marwick, 2015, p. 141). Therefore, this draws further parallels between the Instagram drag performer and a more typical social media influencer, who “monetize their appearance” (Jin et al, 2019, p. 569) thus potentially problematising the heritage and more authentic core of drag performance and its subversive potential. It should be noted that a large majority of all 200 posts collated for this study were found to exhibit this. Performer 3 also tags all posts with a location: “Nottingham” once again highlighting a sense of pride in their residential city and perhaps in the scene they contribute to the construction of, a city which fosters a “growing drag scene” (Brown, 2019).

Discussions of quantitative data is also relevant to this subcategory as the two most successful performers (5 and 3) appear to have a strong focus on close-up selfies that capture and highlight makeup skills, usually paired with links to branded product. Every post assessed (10 each) by both performers was found to predominantly corroborate this. Alternatively, out of the 20 accumulative posts taken for analysis from performers 17 and 16 (whose follower counts are significantly lower), each performer had only 5 posts that focused on their makeup with only 3 posts detailing makeup products used. This demonstrates the preference towards engagement with make-up and beauty-centred content from drag performers, which is hardly surprising given that in 2020 content relating to the beauty industry held 11.1% of all Instagram interactions (Iqbal, 2021). Thus, this is potentially corroborated with prior discussions on the importance of and reliance on make-up focused ‘selfies’.

Another subcategory, is the posting of full body images that focus on the outfit of the performer. Whilst make-up-focused shots were more common, there were instances where the entire outfit and creative fashion skills of the performer were highlighted, even on occasions where the performer had created the actual garments. For example, performer 12 states that they have made the dress they are wearing “by hand”. This takes an even more interesting development where performer 12 in another post indicates that they are wearing “hip-pads made by moi” and a link is posted to another Instagram profile where the performer runs a small business page selling hip-pads to other performers. Here, the performer crosses into several types of influence as they are not only creating content to appeal to drag-interested audiences and therefore increase social popularity, but also draw attention to their own independent-business venture and therefore increase their own economic capital: “the self-negotiates the personal [which is the art of drag here] and professional [the economic venture of the performer] before a mass audience online” (Johnston, 2020, p. 509).

The final subcategory of interest is the uploading of recorded live performances. Although there are only four examples of this, it is particularly interesting when viewed in a post-Covid 19 context. In-person performances at the time of writing and data collection cannot take place due to governmental social distancing guidelines, potentially leading to an influx of recordings of live performances shared on Instagram as over 70% of examples took place after the 1st April 2020 (once the UK had entered “lockdown” restrictions). Two examples were filmed in what looks to be the bedroom and house of the performer whilst in drag and another performer had filmed in what appeared to be a derelict building. Even more interestingly, performer 13 had recorded themselves in front of a green screen, allowing images of planets colliding to appear behind them thematically linking to their “space-age” drag outfit. The use of heavy effects here promoted new ways of viewing drag performance, which would have been unlikely facilitated in a live performance. This performance was also a single performance from a constructed collaboration video that strung together the performances from several other performers from across the UK and internationally with the headline act of Ongina, an incredibly popular former RuPaul’s Drag Race contestant. These performances are used to not only showcase the performative talent and capabilities of the individual performers, but also promote themselves amongst other performers (as discussed earlier). In creating opportunities to market themselves and the drag-based talent they possess to audiences on social media, at a time when opportunities are more limited than ever before due to the ongoing pandemic, “self-branding through social media can be understood as a way to retain and assert personal agency and control within a general context of uncertainty and flux” and therefore harmonize “with neoliberal notions of individual efficacy and responsibility” and the need to overcome (Khamis et al, 2017, p. 200).

Mixing of Private and Drag ’Identities’

This category refers to the evident mixing of Instagram profiles and posts being used for not only drag-based content, but also content that relates more closely to the private life of the performer. Six of the twenty performers were found to have demonstrated this. This category most identifiably resonates with notions of celebrity and influencer authenticity capital. For celebrity (and in this case influencer/microcelebrity), authenticity is introduced as a construct that represents consumer perceptions of celebrities being ‘true to oneself’ (or being ‘their own most authentic selves’) in their behaviours and interactions with consumers. As Ilicic and Webster argues, “celebrity brand authenticity is introduced as a construct that represents consumer perceptions of celebrities being ‘true to oneself’ in their behaviours and interactions with consumers” (2016, p. 410). The first subcategory, which most evidently highlights the utilisation of authenticity as a marketing tool, is the mixing of both explicit mixing of both drag-based posts and posts that are not drag-based and show the everyday lived identity of the performer. This affect of ordinariness is key to the success of an influencer/micro-celebrity’s brand. Performer 9 most consistently posted this kind of content. Several posts on this profile were not exclusively drag-based, including self-portraits (or selfies) revealing the performer’s out-of-drag body in his everyday life. This kind of mixing drag and non-drag-based content to their audiences seems to further and highlight the transformation of drag. Consequently, it might be said that notions of heteronormative gender-subversion that appears to be at the heart of drag as an art/performance-art form are illuminated here, potentially appealing to audiences educated in forms of gender studies. This is because drag is most often considered to “represent a type of gender expression that is not necessarily tied to […] a person’s core gender identity or sexual orientation” (Knutson et al, 2018, p. 33), and representing the performer’s drag identity as separate from their own identity seems to cement this argument. Additionally, the participant illuminates academic perceptions on celebrity authenticity as the crux of reputational success as “consumers value celebrities when they actually are who they appear to be” and that “being oneself in terms of creating an image of individuality, uniqueness, and differentiation” is greatly appreciated and beneficial to those seeking heightened reputations (Ilicic and Webster, 2016, pp. 410-11).

Performers were also found to post photographs which collaged the “before” and “after” of a drag look, as exampled by performer 9. The result here is like that prior discussed within this category, except here and in this way the purpose of the post and its focus on transformation seems to provide the work of the drag performer more validity and seeks to gain recognition from the work that is undertaken to transform into their drag persona as well as potential recognition from the talent (like with category iii), skill, and time it takes to undertake such transformations. Literature suggests that one of the integral aspects of drag is its power to subvert and this would infer that some audiences and demographics would enjoy content focused on this. By utilising and drawing focus to this aspect, the performers can be said to transactionally create and disseminate wanted and more likely to be appreciated content onto social media where “comments, likes, and shares function as social currency and social reinforcement” (Marwick, 2015, p. 142). Therefore, through these examples this category interestingly can be used to contrast some critical views of academics, who believe the neoliberalisation of drag is damaging to the authenticity of drag as it cultivates the “dampening of drag’s subversive potential” (Feldman and Hakim, 2020, p. 387). Although insta-drag may still contain a subversive potential it seems like performers utilise the subversive nature of drag in its radical reaction to heteronormative gender roles and stereotypes for neoliberal intentions. Furthering this argument is the idea that in presenting both the true identity and drag persona of the performer, they allow audiences to view their more “vulnerable” and authentic states of being. Thus the performer plays into notions of being “relatable” to audiences and appearing more “trustworthy” and even likeable, promoting future engagement (Jin et al, 2019, p. 570).

Conclusions

This study has attempted to highlight the methods enacted by drag performers through Instagram to appeal to audiences, which reflect well-discussed neoliberal and entrepreneurial attitudes often linked to drag performers in academic literature. Several methods have been indicated as regular ploys by drag performers to grow their social media followings and overall engagement whilst simultaneously attempting to open economic and social opportunities both within the platform of Instagram (such as making money from content and collaborations/partnerships) and in the physical world (such as promoting physical performances and talent for future opportunities). This paper demonstrates several different, interesting, and appealing ways in which drag performers participate in an ‘attention economy’ on social media, where they feature their performances and brand an entrepreneurial professional identity. Thus, through their continuous engagement with aesthetic imagery, and practice of marketing through that imagery, the drag performers discussed here directly place themselves as marketers within this attention economy, with the hopes of obtaining social, cultural and economic currencies.

There are evident limitations here. Firstly, the sample population was small, however, by focusing the data on the smaller size of Nottingham it is more likely that this small population more representative of the area than if this study was conducted in the same way in a more metropolitan area such as London or Manchester with larger drag populations. Secondly, there is so much more exploration that could be investigated but the intention of this preliminary study was to isolate the ways in which Nottingham-based drag performers use Instagram and begin to assess how that might corroborate arguments made around drag performers’ entrepreneurial use of social media and provide new insights to the study of contemporary drag cultures.

About the author

Zack is a PhD student in the School of Arts and Humanities at Nottingham Trent University, funded by the AHRC Midlands4Cities scholarship programme. His academic background is largely grounded in theatrical research fields (BA Hons Drama – I, MA Theatre – DI). However, his current work is interdisciplinary utilising both theoretical and empirical research methods to investigate socioeconomic mobilisation of communities through drag in the Midlands (with an ethnographic focus on Nottingham’s drag scene). As such, the work sits between sociological, gender-based and theatrical research fields. The current title of my project is: ‘Locating Regional Cultures of Drag in Medium-Sized English Cities: An Ethnographic Case Study of Nottingham’s Drag Scene’.

References

Abraham, A. (2019) ‘Finally! A Sport for Us Gay People!’: How Drag Went Mainstream’. The Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2019/aug/10/how-drag-went-mainstream-rupaul-karen-from-finance-drag-sos (Accessed: 18 February 2021).

Brown, L. (2019) ‘How Nottingham’s Growing Drag Scene is Providing a Safe Haven for Queer People in the East Midlands’, CBJTarget. Available at: https://cbjtarget.co.uk/2019/11/05/how-nottinghams-growing-drag-scene-is-providing-a-safe-haven-for-queer-people-in-the-east-midlands/ (Accessed: 17 March 2021).

Bryman, A. (2015) Social Media Research. Oxford University Press.

Chacon, B. (2018) How to Calculate Your Instagram Engagement Rate. Later. Available at: https://later.com/blog/instagram-engagement-rate/ (Accessed: 5 March 2021).

Chetwynd, P. (2020) ‘Postfeminist Hegemony in a Precarious World: Lessons in Neoliberal Survival from RuPaul’s Drag Race’, Journal of International Women’s Studies. 21(3), pp. 22-35.

Driscoll, C. and Gregg, M. (2010) ‘My Profile: The Ethics of Virtual Ethnography’, Emotion, Space and Society, 1, pp. 15-20.

Feldman, Z. and Hakim, J. (2020) ‘From Paris is Burning to #dragrace: Social Media and the Celebrification of Drag Culture’, Celebrity Studies, 11(4), pp. 386-401.

Hall-Araujo, L. (2016) ‘Ambivalence and the ‘American Dream’ on RuPaul’s Drag Race’, Film, Fashion and Consumption, 5(2), pp. 233-241.

Ilicic, J. and Webster, C.M. (2016) ‘Being True to Oneself: Investigating Celebrity Brand Authenticity’, Psychology & Marketing, 33(6), pp. 410-420.

Inan-Eroglu, E and Buyuktuncer, Z. (2018) ‘What Images and Content Do Professional Dietitians Share via Instagram?’, Nutrition & Food Science, 48(6), pp. 940-948.

Iqbal, M. (2021) Instagram Revenue and Usage Statistics. Business of Apps. Available at: https://www.businessofapps.com/data/instagram-statistics/ (Accessed 5 March 2021).

Jin, S.V., Muqaddam, A. and Ryu, E. (2019) ‘Instafamous and Social Media Influencer Marketing’, Marketing Intelligence & Planning, 37(5), pp. 567-579.

Johnston, J.E. (2020) ‘Celebrity Inc: The Self as Work in the Era of Presentational Culture Online’, Celebrity Studies, 11(4), pp. 508-511.

Ken, D. (2014) Why Engagement Rate is More Important Than Likes on Your Facebook. SocialMediaToday. Available at: https://www.socialmediatoday.com/content/why-engagement-rate-more-important-likes-your-facebook#:~:text=The%20engagement%20rate%20shows%20you,your%20brand%20is%20much%20greater (Accessed 4 March 2021).

Khamis, S., Ang, L. and Welling, R. (2017) ‘Self-Branding, ‘Micro-Celebrity’ and the Rise of Social Media Influencers’, Celebrity Studies, 8(2), pp. 191-208.

Knutson, D., Koch, J.M., Sneed, J. and Lee, A. (2018) ‘The Emotional and Psychological Experiences of Drag Performers: A Qualitative Study’, Journal of LGBT Issues in Counselling, 12(1), pp. 32-50.

Marwick, A. (2015) ‘Instafame: Luxury Selfies in the Attention Economy’, Public Culture, 1(75), pp. 137-160.

Merriam Webster. (2021) Definition of Selfie. Merriam Webster. Available at: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/selfie (Accessed: 4 March 2021).

Myers, L. (2020) How Often to Post on Social Media. Louise Myers Visual Social Media. Available at: https://louisem.com/144557/often-post-social-media#:~:text=Pins%2C%20try%20Tailwind.-,How%20Often%20to%20Post%20on%20Instagram,times%20per%20day%2C%20on%20Instagram (Accessed 5 March 2021).

Lingel, J and Golub, A. (2015) ‘In Face on Facebook: Brooklyn’s Drag Community and Sociotechnical Practices of Online Communication’, Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20(5), pp. 536-553.

Quaan-Haase, A and Sloan, L. (2017) ‘Introduction’, in Sloan, L and Quan-Haase, A. (eds.) The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods. SAGE, pp. 1-9.

Salmons, J. (2017) ‘Using Social Media in Data Collection: Designing Studies with the Qualitative E-Research Framework’, in Sloan, L and Quaan-Haase, A. (eds.) The SAGE Handbook of Social Media Research Methods. SAGE, pp. 181-196.

Usher, B. (2020) ‘Rethinking Microcelebrity: Key Points in Practice, Performance and Purpose’, Celebrity Studies, 11(2), pp. 171-188.