Being With Each Other in the Unknown: Polycrisis, The Art Workshop, and Rehearsing the Radical Imagination

Alex Parry

Download the PDF of this article

Abstract

This article analyses the participatory art workshop in relation to the contemporary polycrisis. Here, ‘polycrisis’ is a descriptive term used to understand interconnected global instability and a call for criticality and radical imagination. This is explored through the participatory art workshop ‘Practices of Refusal: Art and the Obsession with Participation’ that I collaboratively ran as part of Antiuniversity Now, a UK-based platform for radical learning. In this workshop, refusal and non-participation, typically feared modes of participation in group work, are explored as creative acts. In the workshop, we reenact activities from radical pedagogy and dialogical methods from 1970s feminist consciousness-raising groups to collaboratively build a toolkit of ideas for refusal and non-participation.

Through this research, I explore how the explicit and hidden curriculum of the participatory art workshop relates to the polycrisis. I argue that practices of refusal and non-participation are essential forms of agency, both as a means of practising resistance and radical imagination. Yet, practising being together in a liminal space of collective imagination cannot be overlooked. As part of this analysis, I explore how entanglements with institutions form the aesthetics of the participatory art workshop. Therefore, funding and organisational ties should be critically looked at when considering any impacts of art workshops.

Introduction

The polycrisis depicts intersectional crises experienced unequally in the world today. My art practice responds to the contemporary polycrisis by exploring the possibilities of the art workshop as a rehearsal for collective solidarity. To do this, I lay the groundwork by defining what I mean by polycrisis and how the participatory art workshop, and more broadly, social art practice, might be seen in relation to this.

To fulfil this ambition of the workshop, it is essential to learn the lessons from the community arts movement (Hope, 2017). Therefore, I spend time critically analysing how institutions with specific funding agendas can depoliticise these types of practices. Learning lessons from historic social practices might help establish a notion of the workshop away from art galleries that use the art workshop to generate diverse audiences to fulfil funding council criteria or as service provision while the neoliberal paradigm increasingly fails.

I explore these thoughts through an example from my artistic practice – an art workshop I co-ran with artist Sadie Edginton as part of Antiuniversity Now, a self-organised platform for learning. During this workshop, we use liberatory practices from Augusto Boal and consciousness raising dialogical methods originating from 1970s feminist practices to imagine and rehearse refusal as a form of collective care. I explore how imagination is not an individual reflective practice or a tool for individual psychoanalysis per se but a collective and activist practice that makes the world.

A polyphonic alarm in the collective nervous system

‘Welcome to the world of the polycrisis’ — Adam Tooze (2022)

“It’s not a crisis, it’s an ending” — Artist and collaborator Youngsook Choi (Personal communication, 2023)

The Covid-19 pandemic started simultaneously with my PhD research into participatory art workshops. A quake in the globe that did not stop. Yet the impulse for me to run participatory art workshops started in 2008 – the year of the financial crash, when a previous global alarm went off.

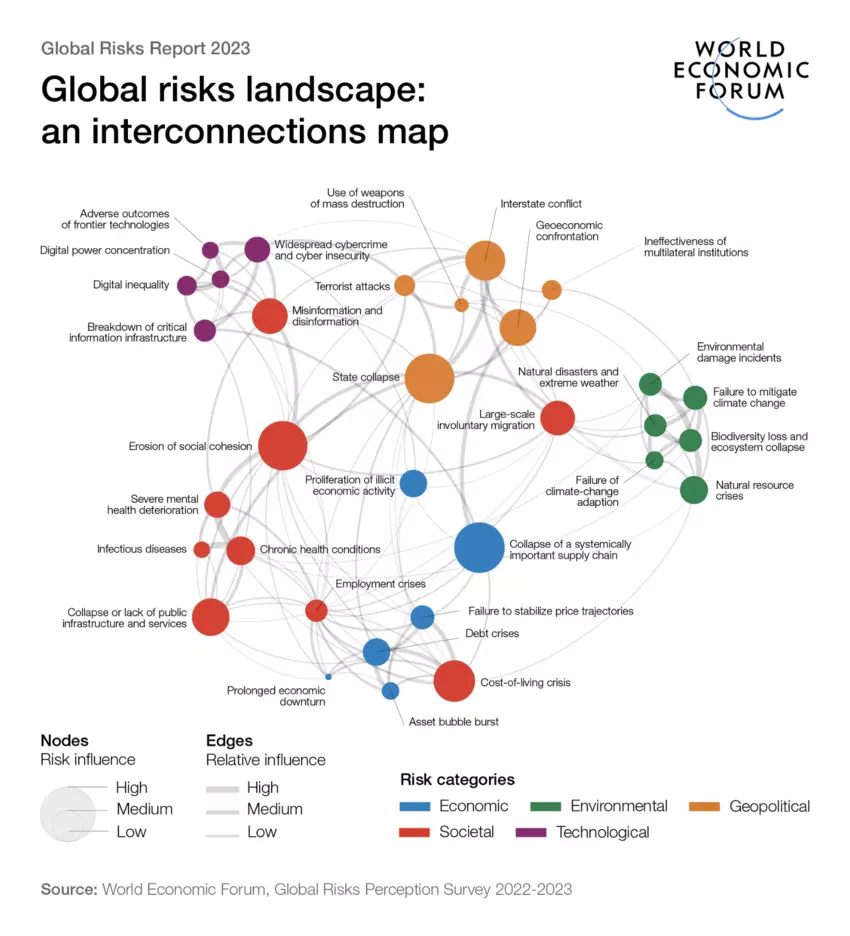

Polycrisis is historian Adam Tooze’s descriptor of the contemporary moment that connects multiple global ruptures. It depicts economic, governmental, and environmental precarity, and it shows, for example, how state collapse, mental health deterioration, and misinformation are all connected. Although this is happening on a profoundly unequal and intersectional basis and has already been experienced by Indigenous, Black, and persecuted people many times over (Maynard and Simpson, 2022), climate crisis and existential threats of human extinction make it impossible for even the whitest, wealthiest people to ignore – even those trying to go the moon (Buncombe, 2019).

Yet images of perpetual crisis keep viewers in the paralysing affect of inaction (Masco, 2017; Henig and Knight, 2023), thus stunning people into failing to focus on alternatives. Such imagery can be ‘counterrevolutionary’ (Masco, 2017), particularly when depicted by mass media intent on raising viewing figures. This bedazzlement keeps critique away from the political conditions or decisions that create these conditions. Indigenous perspectives on ‘crisis’ show how ‘crisis’ has historically been used as a tool of colonialism to justify swift action with detrimental effect to people and planet (Whyte, 2021). When speaking with my friend artist Youngsook Choi in our shared studio about this contemporary crisis, she remarked that it is “not a crisis, it’s an ending”. Youngsook refers to the necessity of this moment not as a disruption of business as usual but a radical and necessary shift away from values of extraction cultivated in intersections of coloniality, patriarchy, and capitalism (see research at The New Institute, n.d). I use this term with these criticisms in mind. Polycrisis, that polyphonic alarm in the collective nervous system, is critical of conditions and a call to new imaginations (action). This is the context and foundation for my approach to the participatory art workshop.

Rise of the Participatory Art Workshop

The workshop-as-form is now a regular part of contemporary art, as international art prizes and biennales increasingly include artists with social practices (e.g. Documenta 15, Turner Prize 2021). However, whilst attention has been placed on social practice, there are some missing links concerning today’s context of polycrisis. Historically, much of the literature has been framed within the context of neoliberalism and the crisis of democracy in the Global North. Attention has been focused on forms of relationality, including dialogue and solidarity (Kester, 2004), antagonism (Bishop, 2012), conviviality (Bourriaud, 1998), and use (Art Útil – Tania Bruguera, 2013). Yet, the polycrisis brings a new set of conditions. It is not only the failure of the economic system driving inequality. It is a mental health crisis, it is mass migration, it is unpredictable natural disasters. It is an ontological crisis (read: necessary shift) of racial domination, patriarchal, capitalist extraction. How then can social art practice respond? Is the existing literature enough to understand the relationship of social art practice to complex global shifts happening today?

The need for a new social practice literature is acknowledged by Claire Bishop’s (2023) re-appraisal of her seminal texts about social practice (Bishop, 2004, 2013). In 2004, Bishop argued that antagonism was previously a necessary tool for social practice artists. This was in the context of the UK’s New Labour government, where ideas about inclusion, Bishop argues, had a depoliticising effect. In this context, antagonism was essential to democracy (Bishop, 2004: 66). However, in 2023, Bishop observed that antagonism has become a tool of the far right and, therefore, is no longer suited as a counter-power tool for social practice. Instead, Bishop suggests that practices of care can run counter to far-right tactics and begin to address legacies of harm towards people of colour.

Yet care and antagonism do not need to sit on a binary spectrum. As the Pirate Care project tells us, care can be ‘disobedient care’ (Medak, 2022). Care can be antagonistic and humanitarian at the same time. This highlights the shortcomings of creating relational binaries, and, concerning the polycrisis, it falls short. Polycrisis is, by definition, complex and deeply woven, thus demanding nuanced and multiple responses. Social practice can be useful, antagonistic, convivial, and a means of solidarity, all at the same time.

Situating the Art Workshop

Social practice has been examined extensively, but art workshops less so, and, as a result, are poorly understood (van Eikels, 2019). Though there has recently been more attention on the subject (Cranfield and Mulvey, 2023; Jordan and Hewitt, 2022), the amount of literature on the subject is still slim compared to the rise of art workshop practices. Whilst in pedagogical theory, there have been many attempts to understand the relationship of education to political transformation (Dewey, 1916; Freire, 1968; hooks, 1994, to name just a few), in contemporary art, the workshop has been subsumed into the broader field of social practice theory, including community art, theatre and dance (particularly from van Eikels, Hölscher, 2021), and the ‘educational turn’ (O’Neill, P. and Wilson, M. 2010) .

When analysing the potential of the art workshop, its structural conditions must be considered. In the UK, art workshops bear an uneasy relationship with institutions. UK arts funding conditions specify the need for institutions to demonstrate public participation. This makes the art workshop a suitable medium to bring in new audiences and raise the number of people participating in activities. This is coupled with state-imposed austerity since the global financial crash in 2008. Since then, the art workshop could be critically understood as more service provision than radical practice (Bishop, 2013).

In the UK, these complications are shown through frustrated ethics. Art institutions might include radical artistic practices or reference some of the issues of polycrisis, but they have dubious and contradictory institutional practices (Quaintance, 2023). This keeps art institutions at ease with the image of radicality (Cranfield and Mulvey, 2023) rather than allowing themselves or the artwork to radically act. On the one hand, this demonstrates recognition that there needs to be shifts, and on the other hand, these changes might be so radical that they may challenge institutions’ very being. The production of a perpetual image of crisis by art institutions might act like the mass media, whose portrayal of crisis keeps people in a form of affect that prevents criticality and action (Masco, 2017; Henig and Knight, 2023).

These institutional tensions are illustrated through a 2011 workshop at the Tate Modern called ‘Disobedience Makes History: Exploring creative resistance at the boundaries between art and life’. This was led by The Laboratory of Insurrectionary Imagination (Labofii), a collective of artists and activists. At the end of the week-long workshop, participants decided to protest Tate’s BP oil sponsorship. When Tate staff discovered this, Labofii was asked to stop the action. In ‘On refusing to pretend to do politics in a museum’, Jay Jordan from Labofii summarises what happened next:

‘Following Labofii’s methodology, the workshop was now entirely self-managed by the participants, and the intervention would be designed by them during the final workshop’ (Jordan, 2010)

Labofii had spent time building skills in collective working so that the group could exist without them. In the workshop, they created an imaginative force embodied by the collective and put it into action. The group became Liberate Tate, whose protests and work eventually led to the dropping of BP’s sponsorship in 2016 (The Guardian, 2016).

This demonstrates the hypocrisy of art institutions that want disobedience to be performed, not enacted (Cranfield and Mulvey, 2023). It shows how the restrictive nature of private and public funding structures can tie institutions’ hands behind their backs. Institutions might need to prove they are working with publics to fulfil state funding criteria, or they may have private sponsorship that can create pressure to compromise values (Quinn, 2022). When obeying the institution and its concerns, the art workshop can thus be a tool to satisfy or retain funding rather than a tool of transformation. From histories of the community arts movement, we see how social art practice has been depoliticised through arts council funding processes (Kelly, 1984) and how these threads run through today (Hope, 2017). By failing to critically understand the role that collaborations with funding bodies and institutions might play in social practice, it may play the same depoliticising role (Jordan and Hewitt, 2022). These funding structures might, therefore, be seen as conditions of aesthetic production.

However, the art workshop has the potential to reappropriate things from institutions (van Eikels and Hölscher, 2021) or it can take place outside of institutions and respond quickly to need. It can be a method of building individual and collective subjectivities (Hölscher, 2019) and, therefore, has the potential to practice creating the types of subjectivities necessary to respond to polycrisis. The art workshop can be a method of empowerment through teaching practical skills, as it was to second-wave feminists who used workshops to train women in practical skills so they did not rely on men for them (D.M Withers, 2019). Today, during the polycrisis, it might be deliberation, new associations, and empathy (Jordan and Hewitt, 2022) that are rehearsed within the workshop – all modes of relationality that the crisis of democracy, neoliberalism, and a swing to the political right are eroding. The ability of the workshop to build new associations is echoed by van Eikels, whose remark captures a simple yet potent truth:

One thing that you are guaranteed to learn in workshops is how to participate in workshops, and the more skilful you and others become in workshop participation the more potential there will be for the creative power of collective attention to work wonders. (van Eikels, 2022)

By attending art workshops, people become more at ease at being together with strangers in creatively diverse and atypical situations. As van Eikels notes, this is a question worth asking, and this is what I also believe has emancipatory potential.

Rehearsing governance

There is an increase in mutual aid practices in the Global North when governments and markets fail to respond adequately to disaster scenarios such as Covid-19 and Hurricane Katrina (Firth, 2020, 2022). Firth’s work on mutual aid practices in disaster contexts provides warnings relevant to the art workshop and its relationship to the polycrisis. First, neoliberal governance is challenged by the climate emergency and other destabilising conditions in the polycrisis. As a result, alternative governing structures are being developed, such as autonomous organising practices or disaster capitalism (Klein, 2007).

Secondly, Firth provides a warning about co-option. By analysing mutual aid practices that emerged during Covid-19 in the UK, Firth shows how mutual aid can be co-opted by hierarchical practices and the logic of new managerialism associated with neoliberalism (Firth, 2020). This demonstrates how performing everyday practices within the neoliberal paradigm acts as rehearsal for futures. Yet concurrently, we might consider that mutual aid practices are also being rehearsed. If so, how might the participatory art workshop be a space where solidarity and mutual aid practices are rehearsed for the types of futures that might occur in polycrisis?

Radical Imagination makes the world

The art workshop is a space to question hegemonies and create new logics. It is a liminal space for radical imaginations to be devised and practised. The radical imagination can be a crucial tool of rehearsal to counter the logic of capitalist hegemonies. The often quoted ‘it is easier to imagine the end of the world than it is to imagine the end of capitalism’ (Fisher, 2009) underlines how the logic of capitalism has been naturalised, and what the role of imagination is in creating this rationality.

Within the context of polycrisis, there are multiple and divergent imaginations about the future, from arguments of postcapitalist abundance exemplified in ‘fully automated luxury communism’ (Bastani, 2019) to ‘preppers’, who rehearse the future as a method of managing disaster and scarcity. These visions present different ideas about the future. They include the ‘imaginative-material’ practices of preppers (Barker, 2019) and the economic–social imaginative practices of post-capitalism.

The urgency of imagining other as part of activist practice might be called the radical imagination. This is different from the imagination as a reflective practice or as a tool for individual psychoanalysis per se, but is an active or activist practice. Writers and educators Max Haiven and Alex Khasnabish write about the importance of radical imagination in social movements. It is, they describe, ‘a crucial aspect of the fundamentally political and always collective (though rarely autonomous) labour of reweaving the social world’ (2010: iii). For them, ‘the radical imagination emerges out of radical practices, ways of living otherwise, of cooperating differently’ (Haiven & Khasnabish 2010: xxviii). What they articulate is an imagination that is embodied and lived.

The radical imagination enables change in a multitude of ways. As sociologist Ruth Levitas (2017) points out in Where there is no vision, the people perish: a utopian ethic for a transformed future, utopia – a concept linked to the radical imagination – can simply emphasise the idea that things can be different. Levitas says utopia can be an ‘education of desire’, an ‘expression of desire’ (2017:6), or a form of prefigurative politics. Practicing desire, and exercising imagination are therefore essential practices to creating change. How can this be rehearsed and practised within the participatory art workshop?

Practices of Refusal: Art and the Obsession with Participation Workshop

Practices of Refusal: Art and the Obsession with Participation is an art workshop exploring refusal as a creative act that I co-ran with artist and long-term collaborator Sadie Edginton in our studio in London. It was a two-hour workshop programmed as part of Antiuniversity Now, which is an open curatorial platform for learning in which anyone can propose to run a workshop or event if it aligns with their set of values such as feminism and anti-fascism (festival.antiuniversity.org, n.d.). Self-organising the workshop through Antiuniversity Now gave us agency to decide on the workshop content and meant we did not have to collaborate with institutions with dubious funding practices.

The workshop was free to attend and open to everyone, although the invitation was directed towards artists with a social practice. During the workshop, we collectively developed ideas for acts of refusal or non-participation in group work. We wanted these ideas to form the basis for a toolkit for artists and educators who are leading participatory projects with others. This would act as means of consciousness raising and awareness of refusal as a creative act, to shift ideas away from binaries between ‘good’ and ‘bad’ participation. Practising this is a recognition that refusal or non-participation is an essential skill in the polycrisis and a prefigurative tool for the building of desire needed in postcapitalist futures. ‘Bullshit Jobs’ have proliferated under neoliberalism (Graeber, 2018), eroding meaning from working lives. The increasing authoritarianism in the UK (Butler, 2023) and many other countries globally (BTI, 2022) shows a willingness by the state to erode democracy, agency, and free speech. At the same time, postcapitalist imaginations promise individuals time to pursue activities and enjoyment (Bregman, 2017). The cultivation of desire and agency is critical to this. Yet, it is a form of participation that workshop leaders dread, who view it as a sign of failure. If refusal or non-participation was reinterpreted as a form of agency and desire, might it be reinterpreted differently?

Agency could be considered as another word for desire. In The Uses of the Erotic, Audre Lorde (1978) describes how, under capitalism and patriarchy, desire, the ability to recognise and follow joy from an embodied perspective has been eroded under patriarchal capitalism. Lorde argues why the logic of desire is a feminist position. The ability to refuse to participate is essential to this. Yet, taking on such agency risks being libertarian or individualistic. How can it be cultivated within a collective context with care for others? These were ideas we wanted to explore within the workshop. Yet rather than performing a set of preconceived answers, we saw this as an opportunity to speculate collectively. The participatory art workshop can open spaces for practising within the field of not knowing, an anthesis to the banking style of education that Freire critiqued in Pedagogy of the Oppressed (Freire, 1968). This space of not knowing is where radical imaginations, those pluralistic possibilities, can thrive.

Refusal before, during, and after the workshop – a word about ethics approval

Before the workshop, I had applied for and received ethics approval for this research from Coventry University, where I am based. Although this process can be critiqued from an arts perspective for creating art based on a hegemonic form of institutional ethics, it meant that I had gone through a process of consideration about the ethics of the workshop. It also meant that I formalised consent for participation. At the start of the workshop, I discussed the workshop as part of my PhD research. I explained that participants could opt in or out of this process and change their mind before, during, or after the workshop. Each participant was invited to read further information about the project. Another form asked participants to consent to or refuse several options, such as being photographed. I created options for participants names to be included in the documentation of the work, which is seen as important acknowledgement of labour and creativity in social art practice, but the inclusion of named participants is problematic when seen through a research ethics lens. This opened questions of how artist researchers curate possibilities for refusal before, during, and after the workshop. This also demonstrates how refusal or consent is an integral part of the artist researcher’s process within the academy. Yet there are many questions raised by this process, including whether there is enough time given to this process during or after the workshop, how the participants are valued as part of the work, whether photographs can be withdrawn when they might have been duplicated in the public domain, whether the outcome of the research goes on to benefit or affect participants’ lives, or whether participants are informed about what happens to the project. It also brings up questions for social art practices outside of academic research, where there are various approaches to formalising consent processes. These are mainly centred around vocal or signature-based approaches to consenting to be photographed or filmed. Yet as the artwork often exists beyond the workshop through documentation participants often are limited in their means to consent or refuse participation.

Refusal in the workshop – activity one

The first workshop activity used a scripted performance and accompanying video to prompt action. The script (included in the appendix) references political and economic theory on post-capitalism and art theory from social practice literature. This was passed around the group, and each participant was asked to read a section. We explained to participants that they could disrupt this group activity to explore ideas for the toolkit of refusal.

Elements of the activity were accentuated to amplify power relations inherent in workshops and group work (i.e. participants were asked to film and photograph the activity, and a microphone was used for participants to speak). We used provocation and participation as a method of stimulating an embodied response. This activity referenced Augusto Boal’s Theatre of the Oppressed workshop methods. Referencing histories of political theatre (Boal, 1992) is a recognition that culture is repeated and renewed. It is an active reflection on practice as a form of rehearsal. We intentionally focused on activities that engaged the physical and dialogical self. For new ontologies to be built, new orientations need to be felt and practised into existence. Focusing on the body, not just speech, is a recognition of what the body has been subjected to under capitalism. In ‘In Praise of the Dancing Body’ (2016), activist and educator Silvia Federici writes about the body as a ground of resistance, as ‘capitalism was born from the separation of people from land’ and has worked to discipline and mechanise the body. The workshop allows the collective body to try something else out together. To perform another within praxis – where practice and reflection are both tools of learning together.

Sadie starts reading the text aloud. I have known her for ten years. I am aware of our familiarity as friends and colleagues, which means reading each other’s words as if our own is both comfortable and yet not. I am next to read. I am standing up, with the accompanying video in the background. I have co-made the structure or ‘rules’ for the workshop, written the text and devised the video. I am standing up and reading while everyone else is sitting down. The knowledge of the content and being a facilitator (rule maker) gives me confidence. I perform myself as a confident facilitator, and I am aware of this power. The text is passed around. In the text there are sections that use a lot of ‘I’, so participants perform as me. For example:

I once worked in a school. I was the lowest ranking member of staff within the art department with the least amount of pay and power. During one meeting, I was very annoyed about a decision being made. I didn’t know what to do. I took my shoes off. A small, insignificant act to show I didn’t agree. I refused to wear shoes in a space where teachers don’t take off their shoes. A few months later, a colleague spoke to me about it. They had seen that it was my registering of annoyance. My subconscious & body were trying to subvert the codes of participation where my voice felt it could not.

Participants embody my words through different intersectional identities. As I am a white cis female, this highlights intersectional power dynamics between the facilitator and participants. I am aware of the task’s problematic nature and the power relationships in which different experiences of agency can be felt.

At some point, one of the participants comments on the text. They say it is jumping around; there are too many ideas. They draw attention to it as a confusing text. Their critical analysis acts as a form of refusal. I feel the shame of being revealed publicly as a lousy writer/theorist/workshop leader. The workshop is working on me.

Refusal in the workshop – activity two

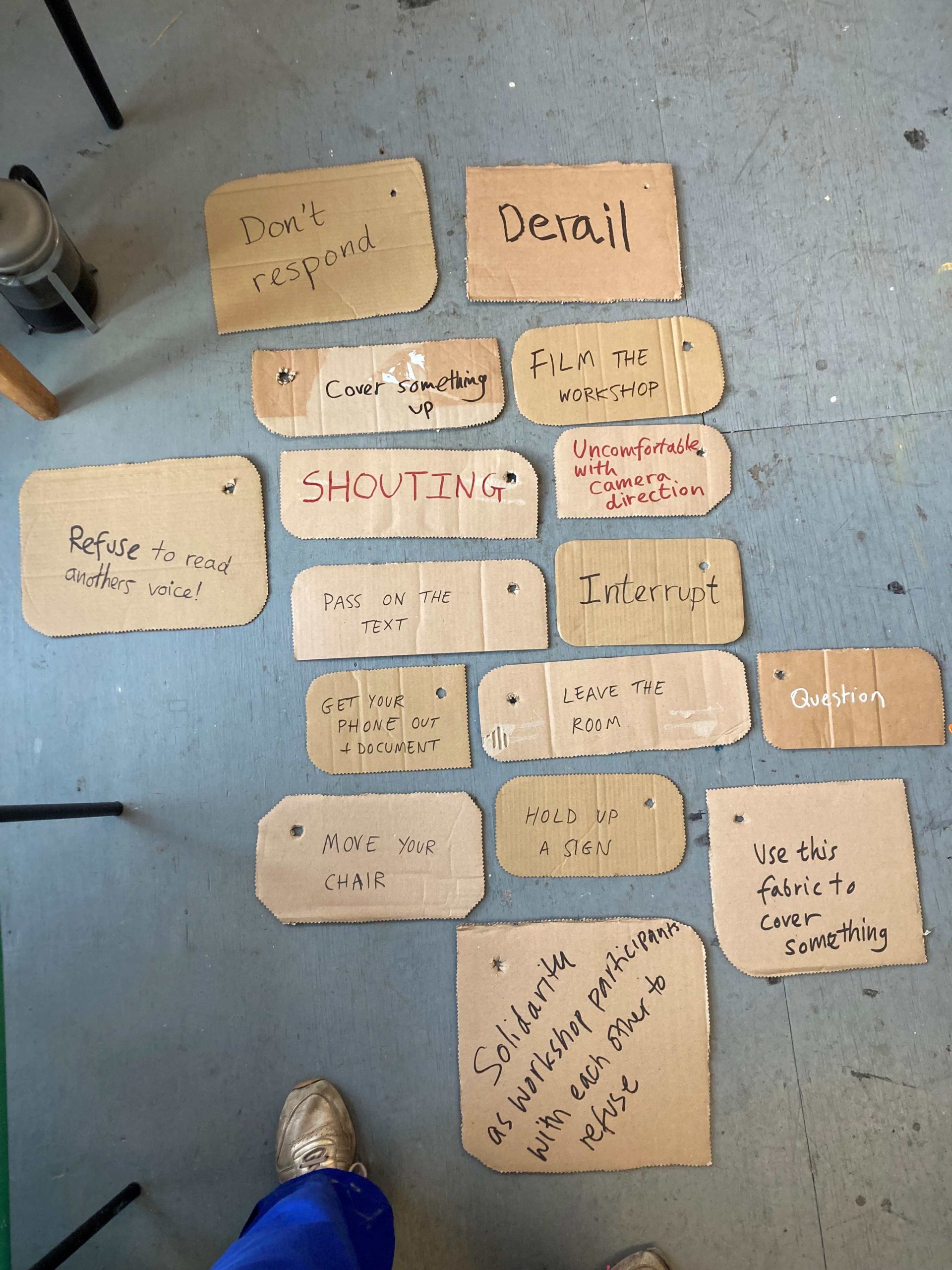

At the end of the first exercise, we reflect collectively on the task. During this discussion, several exciting ideas emerged. These were recorded by participants on cardboard shapes (See Figure 2).

In this conversation, it emerged that there was some confusion from participants who were uncertain whether they were meant to act out forms of refusal in the activity. This could mean we, as facilitators, did not explain things clearly enough. Yet although ideas had not been enacted during the task they had been thought of because of this reflective conversation. For example, through discussing the difficulty of performing refusal, the idea emerged for participants to form bonds of solidarity to enact or support each other in refusing. This opened up many further imaginative possibilities. It highlighted that refusal can be a collective response or form of solidarity amongst participants. It also indicated shortcomings in how we had approached the activity from an individual perspective. Someone else wrote ‘uncomfortable with the camera direction’, which communicates a statement rather than an idea for the toolkit. ‘Uncomfortable with the camera direction’ becomes a form of refusal for the exercise and a means of directly speaking to the viewer of the photograph post-workshop. Therefore, the photographic documentation of the workshop acts as both part of a toolkit and a record of the subjective experience that can be communicated to the secondary viewer.

The question of not risking acting out refusal highlights several things. Irit Rogoff’s article ‘Turning’ (Rogoff, 2008) talks about the role of pedagogy in artistic practice during the rapid neoliberalisation of academic institutions in Europe. Rogoff talks about the vitality of parrhesia, as Foucault saw it, as a crucial response to these processes and as contradictory from the gestural nods of pedagogical aesthetics within the ‘Educational Turn’. For Foucault parrhesia is when;

‘the speaker uses his freedom and chooses frankness instead of persuasion, truth instead of falsehood or silence, the risk of death instead of life and security, criticism instead of flattery, and moral duty instead of self-interest and moral apathy.’ (Foucault, 2001, 20)

Parrhesia always exists in the context of power. In the workshop, power relations exist between the facilitator and the participant and amongst the participants themselves. Yet this workshop highlights how parrhesia, referred to as a speech act, is deeply entangled with action. Parrhesia is here an iterative process of speech and action. The focus on action as integral to parrhesia is highlighted by Beech and Jordan’s (2021) article ‘Toppling statues, affective publics and the lessons of the Black Lives Matter movement’ in which they discuss the ineffectiveness of the voice and language to effect change in the removal of Edward Colston statue, a former trader in the transatlantic slave trade in Bristol. After years of campaigning in words, it was its iterative process with action that was transformative.

In this workshop, I interpret parrhesia in two ways. Whilst it is hard to perform overtly, it can occur more subtly. We wanted participants to enact their refusal, yet, in this case, collective confusion was a form of refusal. This was an unexpected form of refusal. It is me, the organiser, and the hierarchical relations of the group that is challenged. There are always methodologies of refusal, even in a workshop about refusal.

Refusal in the workshop – activity three

Following this, we spent time in small-group conversations to discuss lived experiences of refusal and power dynamics in workshops. Participants discussed examples of refusal or when they would have liked to refuse in workshop spaces. This acted as a form of dialogical consciousness-raising, which was commonly practiced by small groups of women in 1970s feminist practices in USA and Europe. In these meetings women would gather to understand subjective experiences as political. Yet, unlike in second-wave feminism, where identities would cohere around the experience of being a woman (widely critiqued for being centred around the experience of being a white woman), in this group, participation was self-selective and a mixture of gender identities. Instead, group commonality was based on an interest in power relations more broadly in group work and ideas of participation and refusal in social art practice. Yet intersectional experiences are integral to experiences of participation and refusal. Therefore, having a broad mix of people could be limiting or expansive, depending on the broader dynamics of the group (Zheng, 2016). The borrowing of methods consciousness raising talking circles echoes calls from both activist group Plan C as well as academics Firth and Robinson (2015) to reignite the use of small group talking circles as a method of collectively producing knowledge. Plan C writes about providing a space to share and process subjective emotions, whilst relating them to the wider political and social context and ‘constructing a disalienated space’. (Plan C, 2015). Yet I recognise the limitations of the workshop in being able to do this, because of the inherent dynamics of facilitator and participant.

Sharing lived experiences through storytelling and personal experience meant we could start to unpick the often-overlooked elements of group work. We could then begin to articulate more about what refusal is or, through its absence, what it could be. I was in one conversation with two artists who spoke about refusal from the point of view of being a facilitator in an institution where participation is graded. After discussions in small groups, we returned to the large group to share. Repeating and summarising discussion affirmed experiences, yet the absence of narratives also represents forms of refusal, and questions should be asked about what narratives are left out and why. Forms of refusal and how absence holds knowledges.

The hidden curriculum of the workshop

As well as understanding the formally learned elements of the workshop, a hidden curriculum is key to understanding what is being rehearsed. I borrow the term ‘hidden curriculum’ from pedagogical theory, which was developed to explain what students learn unofficially, outside the formally recognised curriculum. I find it helpful for thinking about how art workshops are transformative spaces through both the topics covered, and what is learned when people are simply just together.

In this workshop we might consider the hidden curriculum as both what participants are learning that is hidden from view, as well as through the organisational aspects of the workshop. When activist and poet Walidah Imarisha writes, ‘all organising is science fiction, we are dreaming new worlds every time we think about the changes we want to make in the world’ (Imarisha, 2015: 3) they recognise how we organise, and what we do when we organise matters. Taking this into account, how art workshops are organised before, during, and after the event matters. The hidden curriculum concept highlights how the unsaid matters. In the art workshop, this includes convivial activities such as eating snacks and drinking tea or participants’ access needs. It includes how people are directed and organised in the workshop space and how much freedom is given to participants to perform their agency.

In Silvia Federici’s talk ‘The Politics of Care’, she talks about how during the banking crisis in 2001 Argentina’s collective kitchens were essential to politics (Federici, 2021). Here, food, a socially reproductive activity is made political.

I visited a collective kitchen. I heard the stories about the Piqueteros. You know when the big banking crisis occurred, and people had no money. The money economy collapsed actually they saved the day. They brought big pots into the street, and they began to cook in the streets collectively and make decisions…When the money economy collapsed another economy became visible. The economy that is always invisible yet sustains the world

(Federici, 2021, 41.15min – 41.50min)

Relational aspects of life are always preparation for something more, and in deep crisis and change this is when it might be needed more than most.

Limitations of the Workshop

We found that two hours was insufficient to fulfil the planned workshop. If we had continued the workshop, we would have liked to use some of Augusto Boal’s forum theatre techniques. Forum theatre is a method of theatre developed by Boal for non-professionals, and members of communities as a means of consciousness raising. Here theatre is used as a tool of social and political transformation (Boal, 1979, 1992). We had planned to use this method to perform alternative endings to group scenarios where refusal would have been beneficial. This would have allowed participants to enact further possibilities, bringing imagination into being through performing. As my research is partly about rehearsal and prefiguration, a two-hour workshop is not enough to deeply embed practices. Reflecting on this, we felt that we would need to repeat and practice this activity as a means of building habit.

Conclusion

I started this article by articulating polycrisis as a call to be critical and to act. I have detailed some possibilities of how the art workshop might do this. In the workshop explored in this article, I look at how agency might be practised through refusal or non-participation. I suggest this is an important act within neoliberalism and a rehearsal for something beyond that – in this case, postcapitalist futures. In neoliberal hegemony, publics are training for individualism. It is, therefore, vital that spaces are found in which people can practice being together in creativity and exercise collectivity.

Yet rather than the participatory art workshop as a slick delivery of a well-constructed plan, it is often a space of complexity. Rogoff writes:

‘We hoped to posit that education is in and of the world—not a response to crisis, but part of its ongoing complexity, not reacting to realities, but producing them.’ (Rogoff, 2008)

The ways that participants refuse in a participatory art workshop about refusal might be so subtle that they might only be perceptible to the observer in the documentation or retelling of the workshop experience. When research acts as a method of slowing down, that enables understanding of the workshop in greater detail, it becomes easier to see how refusal or absence is always deftly woven into the workshop by the participants. It is crucial to note refusal or absence as a form of collective and urgent knowledges that speaks loudly of and to power relations.

Understanding the role of the radical imagination can help to see how the art workshop might carve out collective space to speculate and embody futures. Dialogical or action-based prompts in the participatory art workshop can provide a space to exercise imagination in the field of not knowing. Yet the form itself will never be emancipatory without the conditions around it, which are as much part of the aesthetics as the workshop itself. Therefore, careful critical thinking should be done on how social art practice and workshop practices are funded so that the institution does not drive the workshop’s social, political, and economic aesthetics.

About the author

Alex Parry is a practice-based PhD researcher at Coventry University exploring the potential of participatory art workshops during the contemporary polycrisis. She graduated from the Royal College of Art in 2018 with a Contemporary Art Practice: Public Sphere degree. She is also part of the art collective Studio Yea with Eva Freeman and Youngsook Choi, who creates structures of care to support each other in precarious times.

References

About Page (n.d.) available from <https://festival.antiuniversity.org/pages/about> [Accessed 14 March 2024]

Barker, K. (2020) ‘How to Survive the End of the Future: Preppers, Pathology, and the Everyday Crisis of Insecurity’. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 45 (2), 483–496

Bastani, A. (2019) Fully Automated Luxury Communism: A Manifesto. London; New York: Verso

Beech, D. and Jordan, M. (2021) ‘Toppling Statues, Affective Publics and the Lessons of the Black Lives Matter Movement’. Art & the Public Sphere 10 (1), 3–15

Bishop, C. (2022) Revisiting Participation. [online] available from <https://art-of-assembly.net/2022/03/14/upcoming-claire-bishop-revisiting-participation/> [Accessed 14 June 2023]

Bishop, C. (2012) Artificial Hells: Participatory Art and the Politics of Spectatorship. London; New York: Verso Books

Bishop, C. (2004) ‘Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics’. October 110, 51–79

Boal, A. (1992) Games for Actors and Non-Actors. Routledge

Boal, A. (1979) Theater of the Oppressed. Pluto Press

Bourriaud, N. (1998) Relational Aesthetics. Les presses du reel

Bregman, R. (2017) Utopia for Realists and How We Get There. Bloomsbury

Buncombe, A. Why Are Three Billionaires Determined to Go to Space – and What’s the Danger to Planet Earth? (19 July 2019) available from <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/science/elon-musk-space-jeff-bezos-richard-branson-apollo-11-moon-landing-a9011591.html> [Accessed 25 January 2024]

Butler, P. (2023) ‘Hostile, Authoritarian’ UK Downgraded in Civic Freedoms Index [online] available from <https://www.theguardian.com/uk-news/2023/mar/16/hostile-authoritarian-uk-downgraded-in-civic-freedoms-index> [Accessed 26 January 2024]

Choi, Y. (2023) Personal communication conversation with Alex Parry, March 2023).

Cranfield, B. and Mulvey, M. (2023) ‘More than a Meeting: Performing the Workshop in the Art Institution’. Performance Research 28 (2), 4–13

Dewey, J. (1916) Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education. Macmillan Publishing

Documenta Fifteen (n.d.) available from <https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/> [Accessed 25 January 2024]

van Eikels, K. (2022) Presentation as Part of ‘Technologies of Togetherness Conference’.

van Eikels, K. (2019) ‘Two Workshops, How Many Publics? Rirkrit Tiravanija and Koki Tanaka Erect Archival Preserves for Living Together’. Public Matters

van Eikels, K. and Hölscher, S. (2021) Opening Remarks of the Conference The Workshop: Investigations Into an Artistic-Political Format. [online] available from <https://www.ici-berlin.org/events/the-workshop/> [Accessed 26 January 2024]

Federici, S. (2021) The Politics of Care [online] Spitzer School of Architecture. available from <https://youtu.be/3vVtUkaFpYE?si=03Qs23YZ-QkMU0VL> [Accessed 26 January 2024]

Federici, S. (2016) In Praise of the Dancing Body [online] available from <https://abeautifulresistance.org/site/2016/08/22/in-praise-of-the-dancing-body> [Accessed 26 January 2024]

Firth, R. (2022) Disaster Anarchy: Mutual Aid and Radical Action. London: Pluto Press

Firth, R. (2020) ‘Mutual Aid, Anarchist Preparedness and COVID-19’. in Coronavirus, Class and Mutual Aid in the United Kingdom [online] Preston, J. and Firth, R. Cham: Springer International Publishing, 57–111. available from <https://link.springer.com/10.1007/978-3-030-57714-8_4> [Accessed 26 January 2024]

Firth, R. and Robinson, A. (2016) ‘For a Revival of Feminist Consciousness-Raising: Horizontal Transformation of Epistemologies and Transgression of Neoliberal TimeSpace’. Gender and Education 28 (3), 343–358

Fisher, M. (2009) Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? Zero books. Winchester: O Books

Foucault, M. (2001) Fearless Speech. ed. by Pearson, J. Semiotext(e)

Freire, P. (1968) Pedagogy of the Oppressed. New York: Continuum

Graeber, D. (2018) Bullshit Jobs: A Theory. Simon & Schuster

Haiven, M. and Khasnabish, A. (2014) The Radical Imagination: Social Movement Research in the Age of Austerity. Halifax; Winnipeg: London: Fernwood Publishing; Zed Books

Haiven, M. and Khasnabish, A. (2010) ‘What Is Radial Imagination? A Special Issue’. Journal of Radical Theory, Culture, and Action 4 (2)

Henig, D. and Knight, D.M. (2023) ‘Polycrisis: Prompts for an Emerging Worldview’. Anthropology Today 39 (2), 3–6

Hölscher, S. (2020) ‘The Workshop: A Format and Promise Between Collectivity and Individualism’. Peripeti 17 (31), 113–128

Hölscher, S. (2019) From Rehearsals and Trainings to the Workshop: Performing and Visual Art Practices in New York during the 1960s.

hooks, bell (1994) Teaching to Transgress. Routledge

Hope, S. (2017) ‘From Community Arts to the Socially Engaged Commission’. in Culture, Democracy and the Right to Make Art: The British Community Arts Movement. Bloomsbury

Imarisha, W. and Exangel (31 March 2016) What Is ‘Visionary Fiction’? An Interview with Walidah Imarisha. [online] available from <https://exterminatingangel.com/what-is-visionary-fiction-an-interview-with-walidah-imarisha/> [Accessed 24 April 2024]

Jordan, J. (2010) ‘On Refusing to Pretend to Do Politics in a Museum’. Art Monthly March, 334

Jordan, M. and Hewitt, A. (2022) ‘Depoliticization, Participation and Social Art Practice: On the Function of Social Art Practice for Politicization’. Art & the Public Sphere 11 (1), 19–36

Kelly, O. (1984) Community Art and the State: Storming the Citadels. Comedia

Kester, G.H. (2004) Conversation Pieces: Community and Communication in Modern Art. Berkeley: University of California Press

Klein, N. (2007) The Shock Doctrine: The Rise of Disaster Capitalism. Penguin

‘Liberate Tate’s Six-Year Campaign to End BP’s Art Gallery Sponsorship – in Pictures’ (2016) The Guardian [online] 19 March. available from <https://www.theguardian.com/environment/gallery/2016/mar/19/liberate-tates-six-year-campaign-to-end-bps-art-gallery-sponsorship-in-pictures> [Accessed 11 April 2024]

Lorde, A. (1978) Uses of the Erotic : The Erotic as Power [online] [Place of publication not identified] : [publisher not identified] ; [Freedom, Calif. :] : [Distributed by the Crossing Press], 1978. available from <https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/9910109513102121> [Accessed 11 April 2024]

Masco, J. (2017) ‘The Crisis in Crisis’. Current Anthropology 58 (S15), S65–S76

Maynard, R. and Simpson, L.B. (2022) Rehearsals for Living. Haymarket Books

Home – THE NEW INSTITUTE (2024) available from <https://thenew.institute/en> [Accessed 11 April 2024]

O’Neill, P. and Wilson, M. (eds.) (2010) Curating and the Educational Turn. London: Open Editions

Plan C (2015) C Is For Consciousness Raising! [31 May 2015] available from <https://www.weareplanc.org/blog/c-is-for-consciousness-raising/> [Accessed 11 April 2024]

Quaintance, M. (2023) ‘Care v Competition’. Art Monthly March, (464)

Quinn, B. ‘They Moved to Silence and Erase’: Artists Who Sued Tate Speak out (7 August 2022) available from <https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/aug/07/artists-who-sued-tate-speak-out> [Accessed 29 January 2024]

Rogoff, I. (2008) ‘Turning’. E-Flux [online] (#00). available from <https://www.e-flux.com/journal/00/68470/turning/> [Accessed 10 October 2022]

Tooze, A. (2022) Welcome to the World of the Polycrisis [online] available from <https://www.ft.com/content/498398e7-11b1-494b-9cd3-6d669dc3de33> [Accessed 3 January 2024]

Trend toward Authoritarian Governance Continues (2022) BTI

Withers, D.-M. (2019) ‘The Politics of the Workshop: Craft, Autonomy and Women’s Liberation’. Feminist Theory 21 (2)

Whyte, K. 2021. ‘Against Crisis Epistemology’. Handbook of Critical Indigenous Studies. Edited b, A. Moreton-Robinson, L. Tuhiwai-Smith, C. Andersen, and S. Larkin, 52-64. Routledge.

World Economic Forum (2023) Global Risks Landscape: An Interconnections Map, World Economic Forum [online] available from <https://www.weforum.org/publications/global-risks-report-2023/digest/> [Accessed 5 June 2024]

Zheng, L. (2016) Why Your Brave Space Sucks. [15 May 2016] available from <https://stanforddaily.com/2016/05/15/why-your-brave-space-sucks/> [Accessed 30 April 2024]

Appendix

Practices of Refusal: Art and the Obsession with Participation : Workshop Script

You are in a large audience, someone passes you the microphone, and you do not know what to say, but you say something anyway

You are part of a workshop, and you are asked to do more than you want to do because you are exhausted and would rather be at home

You are leading a workshop, and you want everyone to have a good time

You are a workshop leader, and you want everyone to be involved in your activity that you have worked on all week and think will be great

You are a workshop leader, and you do not have the capacity to allow for other activities because there are twenty people, and you have never met them before.

You are in a group discussing a text, and only 2 people are talking. You realise when you come out that everyone felt annoyed by this but no one said anything.

You are leading a workshop, and everyone looks visibly bored. You carry on with your activity as you hope it will work out.

–

Perhaps there is an assumption that as artists making work with people, participation is good. Non-participation is bad. We want to ask in this workshop: How can non-participation be celebrated? How is non-participation or refusal a creative act?

Non-participation or refusal to participate happens in all the workshops we do. It is not always visible. It can be a small or subtle act. Here is a story about a small act of non-participation from my own experience.

I once worked in a school. I was the lowest ranking member of staff within the art department with the least amount of pay and power. During one meeting, I was very annoyed about a decision being made. I did not know what to do. I took my shoes off. A small, insignificant act to show I disagreed. I refused to wear shoes in a space where teachers do not take off their shoes. A few months later a colleague spoke to me about it. They had seen that it was my registering of annoyance. My subconscious & body were trying to subvert the codes of participation where my voice felt it could not.

When refusal or non-participation is made visible or noticed by the workshop leader, attempts are often made to steer people towards involvement.

How do you feel about non-participation?

The arts council wants artists and organisations to quantify. How many people were involved? Were they enjoying themselves? Do you have any pictures?

The organisations we work for need these numbers for their funding to continue. They want photos of people doing things and enjoying it. Performing doing and group enjoyment. Performing participation.

They need money.

Refusal or non-participation might be a sister idea to the idea of antagonism. This idea was made famous in art theory in the context of social art practice in 2012 by theorists such as Claire Bishop. Bishop talked about antagonism as an essential framework for participation in art. This was during the early years of austerity post-2008 financial crash and Bishop argued that austerity policies needed to be challenged. There needed to be more antagonism in social practice – not projects that pretend everything in communities is good. Ten years on and with more division by algorithm, conspiracy theories & global shifts to the right, it is clear that Antagonism is a kind of hell, too. Claire Bishop returned in 2022 to consider this in her talk ‘Revisiting Participation’. She now talks about a shift to CARE as a form of repair in response to USA to white supremacy and as a means of reparation.

We need care and collective solidarity & we need agency and choice. How do we create space for both in the workshop? How is allowing space for non-participation or refusal also a form of care and collective solidarity?

We need to build agency and choice to dissent from bullshit jobs

Agency to imagine other possibilities

Agency to act out other possibilities

Agency to not partake in systems of inequality

Refusal to be part of systems of inequality

We need agency to be ourselves and support others.

When I think about post-capitalist communities, I imagine futures with more collectivity and access to decision-making in our everyday lives and governing structures. I imagine more equality. But I’ve been part of co-ops, and its hard! It’s hard to work as a group. Sometimes, I have felt swayed by the group. Not able to disagree or say no.

My training in the UK, where I have lived most of my life, comes from within the neoliberal paradigm. So, how do we create spaces in our collective contexts that might prepare us for the futures we want? How do we learn collectivity, but also agency within the collective? Agency to refuse, not participate, choose to do something else.

How are we practising for that?

Agency Agency Agency

autonomy

care

What does agency mean? How does it remain aware of the collective needs of the individual? This seems like a sidetrack, but I want to bring in the fantastic poet Audre Lorde – who writes about the Uses of the Erotic. I think Lorde has something beautiful to say about agency through this text. I am going to read it here

Erotic comes from the word eros meaning LOVE.

‘Recognising the power of the erotic within our lives can give us the energy to pursue genuine change within our world, rather than merely settling for a shift of characters in the same weary drama’ (Lorde, 1978: 91)

‘Because we live in capitalist society which defines value by finance ‘profit’ to ‘the exclusion of the psychic and emotional components of that need – the principal horror of such a system is that it robs our work of erotic value, its erotic power and life appeal and fulfilment’ (Lorde, 1978: 89)

how do we create space for desire within the workshop? How do we hold those desire lines of the individual with collective care? How are we building all this within our workshops and practices with others? How is refusal or non-participation also part of this?