Getting Ready (for a Night Out with the Girls)

Hannah Clarkson

Abstract

In Getting Ready (2022), I wear as costume the absurdity and heaviness of chronic autoimmune disease, dressed to excess in non-garments of steel, brass, leopard-print velvet. Getting Ready performs armour as amour, exuberance weighted with earnestness and the efforts of empathy. In an awkward amalgamation of body, shelter, and clothing, it plays with possibilities of dressing-up and making(-believe) when caught in uncertain realities, culminating in the gentle, unwieldy gesture of tying my shoes.

Here, documentation of that performance, and other artworks since, accompanies auto-theoretical reflections on the act of dressing up—getting ready—for a day in the life of a chronically ill body. What can be learnt by dwelling excessively—exuberantly—in the body one is in? Dressing up to the nth degree fosters playful strategies of resistance which acknowledge pain and the effort required for hope and joy in times of bodily crisis, gently prising open a space for refusal and repair.

Extending the act of getting ready to a night out with the ‘girls’, I posit archival research as imaginary friendship, sharing wardrobes with artist Frida Kahlo, theatre designer Jocelyn Herbert, and actress Billie Whitelaw to explore how making, wearing and performing in costumes can produce speculative and embodied knowledge which acknowledges care in constraint; collective imaginaries across time, bodies, performative practices.

“Every time she gave a party she had this feeling of being something not herself, and that every one was unreal in one way; much more real in another. It was, she thought, partly their clothes …”

– Virginia Woolf, Mrs Dalloway

“It is perhaps a little soon -to make ready -for the night … and yet I do – make ready for the night”

– Samuel Beckett, Happy Days

We are planning on going out tonight, the girls and I. Dressing up, getting ready. Honestly, I would rather just go to bed. The girls wouldn’t mind, I’m sure. I put on my best dress nonetheless, or the best one for today, by which I mean the one which fits my body most comfortably. Not quite a pyjama party, but a party dress in bed. Not the sequined one, though—too scratchy; nor the velvet—too staticy; nor the polyester—too sticky; but the cotton lets me breathe, though crumpled, and the colour is nice mismatched with the faux fur leopard print softness. The girls wear their best dresses too, though hidden beneath a mound or a blouse or a blue jumper.[1]

*

How does one dress up—get ready—for a day in the life of a chronically ill body? What can be learnt by dwelling excessively—exuberantly—in the body one is in? How might dressing up to the nth degree foster playful strategies of resistance which acknowledge pain and the effort required for hope and joy in times of bodily crisis, gently prising open a space for refusal and repair?

In my 2022 performance, Getting Ready, I wore as costume the absurdity and heaviness of chronic autoimmune disease, dressed to excess in non-garments of steel, brass, leopard-print velvet (Figs. 1 & 2). Getting Ready performed armour as amour, exuberance weighted with earnestness and the efforts of empathy. In an awkward amalgamation of body, shelter, and clothing, it played with possibilities of dressing-up and making(-believe) when caught in uncertain realities, culminating in the gentle, unwieldy gesture of tying my shoes.

So, extending the act of getting ready to preparing for a night out with the ‘girls’, I begin to think of archival research as imaginary friendship, sharing wardrobes with artist Frida Kahlo, theatre designer Jocelyn Herbert, and actress Billie Whitelaw to inhabit collective imaginaries across time, bodies and performative practices.[3] Through their art and archives, I explore how making, wearing and performing in costumes can produce speculative and embodied knowledge which acknowledges care in constraint.

*

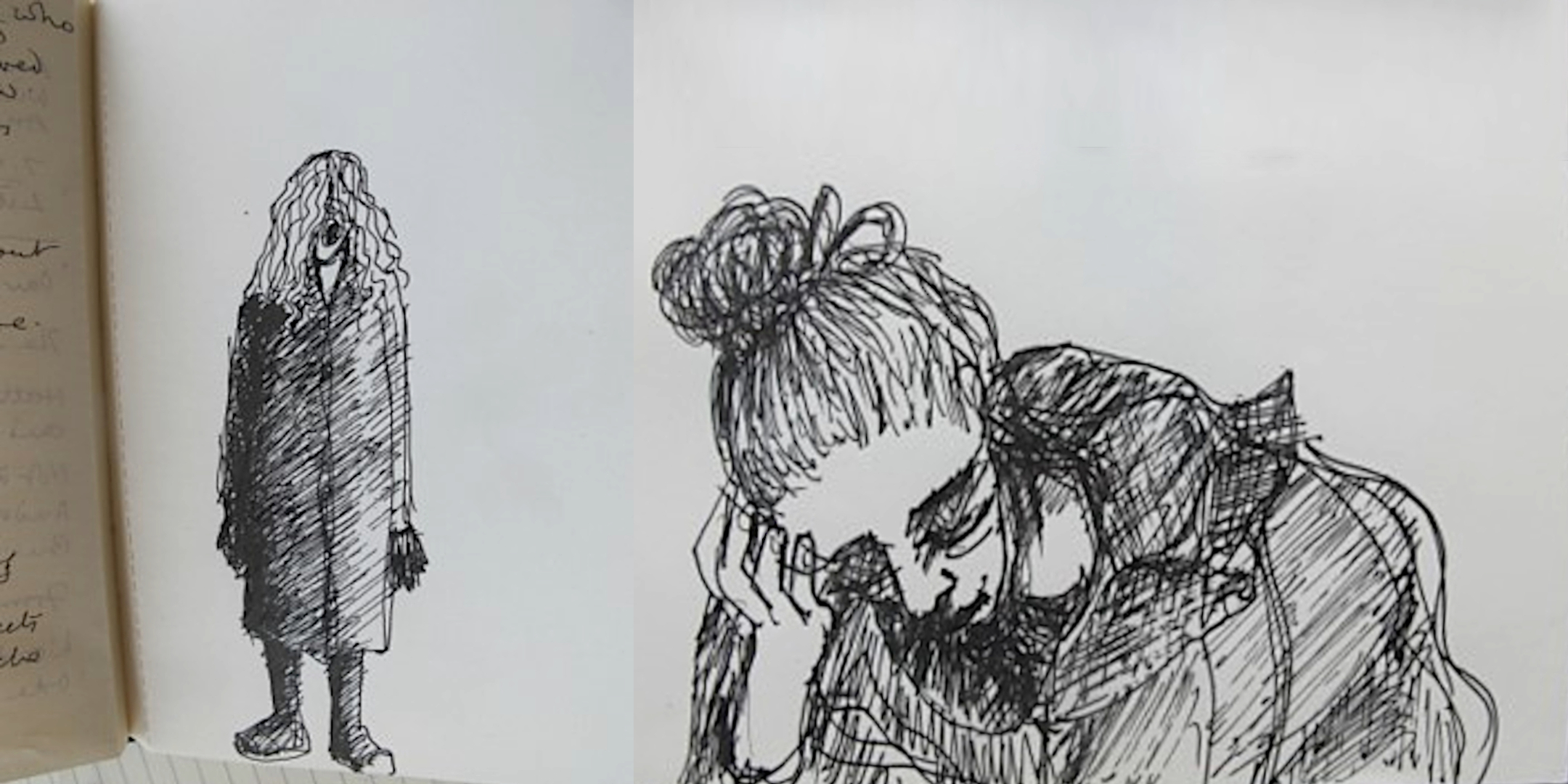

I’ve been spending a lot of time with Jocelyn and Billie lately. Immersing myself in Jocelyn’s archive—amongst her sketches, working notes, shopping lists, to-do lists, drafts for letters to colleagues and friends, models and masks—I find myself increasingly thinking of the designer as a relative or friend (Figs. 3 & 4). This is an imaginary relationship, one-sided yet intimate nonetheless. It is an affinity grown into affection, what Rita Felski might call the “attunement” whereby we are “drawn into a responsive relation” with works of art and, by extension, their makers (Felski, 2020: 41). Indeed, I am reminded of my grandmother: her compulsion to write everything down, lest she forget; her eye for colour and fit; her kindness. Like Jocelyn, my grandmother liked to draw. I inherited this from her.

This week, the first in December 2023, we’ve been hanging out in the gallery at Wimbledon College of Art, where Jocelyn’s archive was formerly held, hanging an exhibition of Jocelyn’s designs for Billie in Samuel Beckett’s plays (Fig. 9). I have made costumes for Billie, too, though I’d be lying if I said they weren’t also for Jocelyn, and for me.

In our shared wardrobe, there is a quilted coat patched together from furnishing fabric samples and cut like a kimono, padded with the comfort of home. It is to be worn with a dungaree skirt of four fabric-covered swimming rings (Fig. 5). These are difficult to inflate, but I empty my lungs to fill them so that Billie can float away, endless pacing footfalls relieved by air and water when the curtain comes down and the play is done. May, Billie in the play Footfalls (Fig. 6), “has not been out since girlhood” (Beckett, 1984: 241). I hope she will come out with us tonight; “slip out at nightfall” (1984: 241) for a walk, at least.

In Footfalls, walking is just as important to the rhythm and pace of the play as the words spoken: “Pacing: starting with right foot (r) from right (R) to left (L), with left foot (l) from L to R. Turn: rightabout at L, leftabout at R. Steps: clearly audible rhythmic pad” (Beckett, 1984: 239). Jocelyn stuck sandpaper to the bottom of Billie’s shoes so that her footsteps scratched the floor beneath and the ears above them. All that walking even at home, it’s no wonder her character never makes it out the door.[4]

There is a metal coat too, hydroformed steel puffed up in two pieces for the two acts of Happy Days (Figs. 7 & 8). Preparing for the play like two children on the beach, Jocelyn, at Sam’s instruction, had buried Billie up to her waist in a mound of earth, then up to her neck (Fig. 10). Re-envisioned via that meme of the Pope in a giant AI puffer coat, armour-like and protective, there is something claustrophobic about this heavy garment that traps me every time I try to wear it.[5] I wonder if Billie gets the same feeling when she puts this on as when she settles into the mound. I’ll help her in and out of it when she says so, not when Sam does.[6] Held still doesn’t mean stillness. Billie is a little taller than I am so hopefully it doesn’t cover her mouth and she can speak.

There is claustrophobia in pretending, too; it takes effort to veil one’s efforts. Carolyn writes of another night out, leaning against the bar in a fabulous cape, thin from throwing up, being complimented by another girl on how great they look. Dressed up, the body drapes its suffering in something softer: “Linen and silk— my placebo, snake oil and armour. I am walking, eating, talking, being in the world—passing, DUPING everyone into thinking that I am one of them!” (Lazard, 2017). Just as clothes embrace us, our “embrace of the ambivalent sick pleasures of dressing … illuminates the radical, reparative potentialities of self-care: small habits and gestures that become resources of sustenance, survival, and joy. Such habits accrete, flourish with excess and ritual” (Butler and Blackshaw, 2023).

Jocelyn is on DIY, putting up shelves inside the stage-set to hold props with enough room for rabbits to hide, too.[7] Home and the hidden, recovery and staring into space, these are also features of chronic illness: staying hidden at home; the ambivalence of rest; zoning out when energy is depleted. The mound isolates both the character of Winnie and the actress Billie in a Beckettian time that plays out at the pace of illness, at once quick and slow. In my re-imagining of the Happy Days mound, the invisible is made visible, dressed up in the comfort of a community of rabbits (Fig. 9). It is precarious, this mound of bunnies, and we spend hours playing Jenga with papier-mâché ears and faux-porcelain cottontails.

*

Afterwards, we need to sit down. Not in the chair Jocelyn made for Not I, but in the salon, side-by-side in conversation (Fig. 11). Not a monologue this time: the silent auditor is invited to take a seat, take part in the conversation as a companionable figure or a friend.[8]

I pull up a chair for Frida, too. I want to share some things with her, to read my diaries to her just as I read hers aloud at home alone. To borrow Emily Rapp Black’s sentiments in Frida Kahlo and My Left Leg, I want to say: “I’m real. I need you. Tell me everything” (Black, 2021: 7). Yes, “I want to talk to Frida about suffering”, but more so to “drop through [the] portal of Frida’s imagination and meet her on the other side of every possibility, as her true friend, no longer imaginary” (2021: 25). I feel the same about Jocelyn and Billie. Sitting here in a row, Frida listens to me while I listen to Jocelyn, who in turn listens to Billie. We all have encouragements to share.

For Frida, I have made a grey suit, felt formed to the shape of legs remembered and a jacket flattened against the wall of a metal and glass booth (Fig. 13). It is not dissimilar in style, fit or defiance to the one she wears in a 1926 family photograph, flanked by female family members in dresses; or the one she stole from husband Diego Rivera for a 1940 self-portrait (Fig. 14), in which she sits surrounded by chopped off strands of her own hair (Porter, 2021: 41). Above her head, she has written the lyrics of a popular Mexican song: “Look, if I loved you it was because of your hair. Now that you are without hair, I don’t love you anymore” (Kahlo, 1940). The outfit is sadly stiff, scratchy and not very comfortable, but I have embellished the suit, and the story, with pearl buttons, just as her story is scarred and dusted with gold.[9] The shared wardrobe I am creating is an attempt to understand, to share stories and to step in one another’s shoes. Strange white pointy boots, scuffed at the toe, as per Sam’s directions. High heeled, though, holding voices; prosthetic imagination and ill-fitting empathy.

Frida was no stranger to bodily discomfort or constraints, nor to the imaginary leaps made in an effort to bear them. In The Two Fridas (1939), she depicts a grown-up version of an imaginary friendship she began when she was six years old, confined to bed with polio. One Frida wears traditional Tehuana costume, a broken heart bloodstain on her dress. Sitting alongside, holding her hand, is another Frida, in modern European clothing (Fig. 12). In a 1950 diary entry, she describes this other Frida not through her clothing, but through her movement: “I don’t remember her appearance … But I do remember her joyfulness – she laughed a lot. Soundlessly. She was agile and danced as if she were weightless. I followed her in every movement and while she danced, I told her my secret problems” (Freeman, 1995: 246). Just like Emily, “I wanted that magical friendship to be mine and Frida’s … in my dreams I was the imaginary girl (Black, 2021: 7). Reading these words, also wishing Frida was writing about me, I want to dance too.

*

We are planning on going out tonight, the girls and I, dressing up, getting ready. Going out in these guises is a heavy task, but we take it lightly—the pain was held prior to the making, after all. We are padded in the cover of comfort, embellished in strange honesty, too scuffed to speak. Hidden here in imaginary fitting rooms, we help one another dress up in shields, girls breathing into a jacket made to collectively wear. The coat is not a coat, more like a shell, but velvet limbs form a collar and I can just about get my shoes on to get out the door. We share it, this jacket, though it has morphed into three or four. We share the comforts and scars and ailments it both conceals and reveals in and on and between us. We share the knowledge that it ordinarily could or would not be worn. But these are no ordinary women. We are kin in the skins we are in, and we own these bodies; embellish the stories they tell with pearls and cashmere and gunmetal and gold.

Yet, gladrags on, we can’t decide where to go. Perhaps we’ll stay here a while longer, play a little longer, act as though the party is right here.

[1] In her role as Winnie in Samuel Beckett’s Happy Days (1961), actress Billie Whitelaw is confined to a mound of earth. Beckett’s stage designer—and Billie’s friend—Jocelyn Herbert, often wore blue, her family have told me.

[2] Carolyn Lazard is an artist and writer who uses their experience of chronic illness to examine ideas of intimacy, labour and care, for example in essays such as Colostomy Fannypack (2017) and How to Be a Person in the Age of Autoimmunity (2013).

[3] Frida Kahlo (1907-1954) was a Mexican painter known for intense self-portraits depicting her various bodily ordeals, from childhood polio to a teenage bus accident. She taught herself to paint during her recovery between the numerous operations that followed the accident.

Jocelyn Herbert (1917-2003) was a stage designer and a key influential figure in modern theatre. Herbert worked closely with Samuel Beckett on the first productions of many of his plays, including Footfalls, Happy Days and the first UK performance of Not I. The Jocelyn Herbert Collection at the National Theatre Archive consists of extensive examples of the designer’s work, including prints, drawings, sketchbooks, masks, model boxes, notebooks and correspondence, providing a fascinating glimpse into the role of the designer in 20th century British theatre.

Billie Whitelaw (1932–2014) was an actress who collaborated closely with Samuel Beckett for more than two decades. She is perhaps best known for her interpretations of Not I, Happy Days and Footfalls, in all of which she worked with Jocelyn Herbert.

[4] Beckett’s Footfalls was first published by Grove Press, New York, in 1976. The play follows a middle-aged woman who has lived at home taking care of her mother, now elderly, all her life. The first performance, at the Royal Court Theatre, London, on 20 May 1976, was directed by Beckett himself with Billie Whitelaw in the lead role and costume and set designs by Jocelyn Herbert. “Sandpaper was attached to the soles of Whitelaw’s soft ballet slippers” so that every step could be heard (Knowlson, 1996: 624).

[5] An image of Pope Francis wearing an oversized white puffer jacket went viral on social media in March 2023, causing a frenzy among the fashion set. The pictures turned out to be computer generated, and have been described as “the first real mass-level AI misinformation case” (Stokel-Walker, 2023).

[6] Samuel Beckett placed great importance on the stage directions both when writing his plays and directing them, though there were instances where the production design or performance were edited in collaboration with Jocelyn or Billie, respectively.

[7] Built into the mound Jocelyn Herbert created for Happy Days were small recesses to hold props close at hand: an umbrella, a handbag, a gun. Not written in the stage directions, however, nor aligned to Herbert and Beckett’s shared minimalistic approach, were the porcelain bunnies that Billie Whitelaw placed there to make herself at home: “After Not I the mound was freedom. Jocelyn had made little indentations so I could place the props very precisely where Sam wanted them. The set became my home. I’ve got hundreds of little china rabbits and I had about thirty of these underneath the mound so it was quite alive and very cosy […] to use Sam’s word, I could ‘recover’ … I would sometimes sit and stare into space … then start off again” (Herbert, 1993: 222).

[8] Watching Beckett’s Not I (1973), one sees only the floating ‘Mouth’ and, barely visible, a shrouded, silent ‘Auditor’ stage left. The audience cannot see the chair keeping actress Billie Whitelaw in her place: “My head was clamped in otherwise I’d get the shakes and it would start to quiver”. Blindfolded, Whitelaw is situated in the comfort of her choosing, in a cage-chaise constructed for her in a gesture of care. To take this further, what if Mouth were to settle into a salon chair instead, side-by-side with a listening companion rather than a silent Auditor? What would they talk about? How might the care designed into this chair prompt conversations around ‘self-care’ and friendship, an opportunity for togetherness and transformation?

[9] On September 17, 1925, Frida Kahlo was seriously injured in a bus accident, leaving her bedridden for months, and in a body brace to keep her spine in alignment long after that. Somehow, Frida’s clothes had been ripped from her body in the accident, and, even more bizarrely, a fellow passenger’s package had burst open to shower her in powdered gold (Lary, 2023).

About the author

Hannah Clarkson is a writer and visual artist with an interest in storytelling, voice, and embodied languages of empathy. Following a BFA from Ruskin School of Art, Oxford University (2013) and an MFA from Konstfack, Stockholm (2017), her current practice-led PhD at Royal College of Art, London—The Absurd Art of A(r)mour: Playful Strategies of Resistance, Costumes of Care and Decorum for the Autoimmune Body—investigates fictioning-as-resistance through artistic and literary expressions of autoimmunity, absurdity and armour. Recent publications include: a short story and poetry collection on Shelter (ed., 2020); The Green Room: Perspectives on Artistic Research (ed., 2018); and ‘Raising the Voice’ (Journal of Artistic Research, 2021), an essay on voice and narrative in contemporary sculpture. Clarkson teaches creative writing for artists at Royal Institute of Art, Stockholm, leading courses investigating shelter through experimental storytelling; writing and artistic practice as tools for expressing bodily experience of illness and gender; scores, voice and the performative ‘everyday’ body; and discursive, decolonial approaches to creative writing and architectural practice-led research.

References

Beckett, S. (1984) Collected Shorter Plays. New York: Grove Press.

Beckett, S. (1961) Happy Days: A Play in Two Acts. New York: Grove Press, Inc.

Butler, A. & Blackshaw, G. (2023) Sick Women Correspondents: Practices of Care in Cross-historical Love Letter Writing. MAI: Feminism & Visual Culture. [online]. Available from: https://maifeminism.com/sick-women-correspondents-practices-of-care-in-cross-historical-love-letter-writing/ (Accessed 25 January 2024).

Clarkson, H. (2023) 31 China Bunnies and an Umbrella in Flames. [Sculpture] 150 x 80 x 80 cm.

Clarkson, H. (2023-24) All the Time the Buzzing. 2023. [Sculpture] 90 x 120 x 100 cm.

Clarkson, H. (2022) Getting Ready. [performance]. Southwark Park Galleries, London, 19 March.

Clarkson, H. (2023) – No Better, No Worse – No Change – No Pain –. 2023. [Sculpture] 160 x 80 x 80 cm.

Clarkson, H. (2023) Pause for Breath. 2023. [Sculpture] 100 x 80 x 80 cm.

Clarkson, H. (2023) The It-Doesn’t-Matter-Quite-so-Much Suit. 2023. [Sculpture] 120 x 60 cm.

Felski, R. (2020) Hooked: Art and Attachment. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Haynes, J. (1979) Happy Days – scene from the play by Samuel Beckett [photograph].

Herbert, J. (1993). Jocelyn Herbert: A Theatre Workbook. Cathy Courtney (ed.). London: Art Books International.

Herbert, J. (1976). Sketch for Footfalls. [Ink on paper]. National Theatre Archive, London.

Herbert, J. (1994). Sketchbook. National Theatre Archive, London: JH/3/63.

Kahlo, F. (1940) Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair. [oil on canvas] 40 x 27.9 cm. Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), New York.

Kahlo, F. et al. (1995) The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait. London: Bloomsbury.

Kahlo, F. (1939) The Two Fridas. [oil on canvas] 173.5 x 173 cm. Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City.

Kahlo, G. (1926) Photograph of Frida Kahlo with her three sisters and a male cousin, Coyoacán, Mexico.

Knowlson, J. (1996) Damned to Fame: The Life of Samuel Beckett. London: Bloomsbury.

Lary, M. H. (2023) Frida Kahlo Accident: How a Single Day Changed an Entire Life. History Cooperative [online]. Available from: https://historycooperative.org/frida-kahlo-accident/ (Accessed 25 January 2024).

Lazard, C. (2017) Colostomy Fannypack. The Deaf Poets Society: an online journal of deaf and disabled literature and art. [online]. Available from: https://www.deafpoetssociety.com/carolyn-lazard (Accessed 26 January 2024).

Lazard, C. (2013) How to Be a Person in the Age of Autoimmunity. Cluster Mag

Porter, C. (2021) What Artists Wear. London: Penguin Books. [online]. Available from: https://www.penguin.co.uk/books/314590/what-artists-wear-by-porter-charlie/9780141991252 (Accessed 26 January 2024).

Rapp Black, E. (2021) Frida Kahlo and My Left Leg. Kendal, England: Notting Hill Editions.

Stokel-Walker, C. (2023) Should you be worried that an AI picture of the pope went viral? [online]. Available from: https://www.newscientist.com/article/2366312-should-you-be-worried-that-an-ai-picture-of-the-pope-went-viral/ (Accessed 24 January 2024).

whole body like gone: Jocelyn Herbert and Samuel Beckett (2023) [exhibition] Curated by Hannah Clarkson. Wimbledon College of Art, London, 1 – 7 December.

Woolf, V. (2020) Mrs Dalloway. London: Penguin Classics.