Rivers, Webs and Nets: Channelling Creative and Collective Enquiry at Heart of Glass

Emeri Curd, Patrick Fox, Emily Gee, Kate Houlton

Introduction

This article explores a collective approach to learning, research and knowledge production at Heart of Glass, a community arts organisation based in Merseyside in the North West of England. Everyone we work with – artists, communities, groups, partners, producers – are active collaborators in the creation of community art and creative spaces. Learning and research lives across all our programmes. Making this kind of work visible is increasingly challenging as we navigate monitoring, evaluation and value-driven research. As an organisation, we hope to challenge normative research frameworks and evaluation methods that put our collaborators in boxes, assign them numbers or pathologise their experiences. We want to create space to hold, reflect on and articulate this practice and the work we produce together.

This approach to research and practice is akin to this special issue of Makings Journal, ‘Gentles Gestures: Contexts, Spaces and Approaches beyond the Academy’. Alongside artists and communities, Heart of Glass creates spaces for making and learning outside institutional settings. It could be argued that these liminal, “grey spaces” of knowing and unknowing challenge traditional colonial hierarchies of knowledge promoted by “Places of Power” (Hardt & Negri, 2000, pp.212) that “collect, exhibit and educate” (Ashley, 2005, pp.32). With no specific venue to instruct our work, we have the freedom to build and rebuild, articulate and rearticulate the conditions in which the work exists and thrives. Differently to academic spaces or courses teaching socially engaged practice, our learning programme is in continuous motion to challenge and investigate the commodification of education, learning and the language of community arts.

Context

Formed in 2014, Heart of Glass began as a concept, articulated through a funding application and proposed action research project to test an alternative method of community arts provision in St Helens. Initially based at St Helens Rugby Football Club and supported by a consortium of partners, our original funding support came through Arts Council England’s Creative People and Places programme which we continue to receive to this day. We became formally constituted as an organisation two years later in 2016. Our principal aims were to support a range of community and place-based practices, focussed on four key questions for our work at the time. Patrick Fox, our CEO recalls the following foundational enquiries:

- How could we support meaningful collaborative and enquiry-based work to develop, bringing artists and communities together?

- How could we develop and advocate for what ‘the arts’ role might be in a broader civic context, where might the arts speak to the democratic deficits and challenges experienced by our community and broader society?

- How might we understand and support meaningful participation (and actively question what this means) across our locale – audiences, collaborators, partners and supporters?

- How could our work inform and support the development of collaborative and socially engaged methodologies and practices nationally and connect with other forms of community-based practices, locally and internationally?

Since then, our enquiries have shifted as we strive to embed feminist (Wakefield, & Koerppen, 2017) and permaculture (Mollison & Holmgren, 1978) ethics and principles to pursue a more holistic approach to monitoring, evaluation and learning (MEL). By doing this we hope to co-create an ever-evolving set of practices of qualitative, dialogic and creative reflective tools to gather learning. Through these methods we seek to understand the theoretical implications of being a social justice-led, regenerative, learning arts organisation.

Defining our practice

Lately, we have opted to use the term ‘community arts practice’ to describe our work. We use this term to reclaim the radical potential of The Community Arts Movement between 1968 and 88 in the United Kingdom (Jeffers, 2017, p.1). Particularly in the context of this article emphasising the collectivity of voices that make up enquiries towards cultural democracy, “community arts” (Kelly, 1981) seems appropriate. Similarly, this method of practice signifies the context of our work within the communities we are embedded within and stresses the importance of a contextualised history of community organising and art-making in relation to class. Here we use Welsh theorist Raymond Williams’ description of culture to define our work to provide space where; “consciousness really does change, and new experience finds new interpretations: this is a permanent creative process” (1961, p.381). This description of the culture intersecting with democracy is in keeping with our work to challenge the idea of discomfort with the unknown in collaboration with others. We see this as an ongoing process to create spaces of co-enquiry that prioritises action and practice, acknowledging that theory can be important to take steps towards change (Lukacs, 1923, p.2). Crucially though, this understanding should not be prioritised over the practice of community arts and the experience of ‘being’ with people.

Fundamental in this work is the producer role. Within a typical Heart of Glass project, a producer journeys alongside the creative process each step of the way in close contact with both artists and communities. An embedded approach, this role flexes to the agreements made by artists and communities project-by-project and is negotiated in dialogue. Often, producers have lived experiences of some of the themes, topics and locations explored in the projects and therefore are both knowledgeable of the context and committed to the work. The producer role is described by University of Central Lancashire in their evaluation study on our work ‘Developing Collaborative & Social Arts Practice: The Heart of Glass Research Partnership 2014—2017’ as:

psychologically, emotionally, and practically containing work, which helps to reduce the difficulty and anxiety of working in challenging contexts that often demand capacities and abilities not conventionally thought of as part of the artist’s skill set (UCLAN, 2018, p.14).

Writing the work

The approach to this paper is iterative – meaning that each conversation here informs the next – and creates a picture of how knowledge, research and learning lives across all our work. Not only multifaceted but conflictual at times; the work comes from positions of shared values and principles as opposed to rehearsed or repeated organisational aims and objectives. During the writing of this paper – and throughout our ongoing, cyclical work in this field – we have sought influence from the influential text, ‘We Make the Road By Walking It’ (Horton and Freire, 1990). Hence, this article can be interpreted as an ‘in-conversation piece’ where we ‘speak’ the work. In keeping with Horton and Freire, “the purpose is to have a good conversation but in the sort of style that makes it easier to read the words” to “capture this movement of conversation” where “the reader goes and comes with the movement of the conversation” (p.4-5). It is more than likely that there was an easier way for us to write the article. Naturally, the work mirrors much of the ‘messiness’ of our practice, and true to form, we took the long route. Therefore, this paper captures the different temporalities, circumstances and durations of the conversations to create the work. Each conversation featured here represents different ways of reflecting, and relationships to speaking, reading, writing and theorising research and reflection.

In this article there are three vignettes written and discussed in dialogue with three staff members in the research principles working group; Patrick Fox (Creative CEO), Emily Gee (Senior Producer) and Kate Houlton (Children and Young People’s Producer). Through a number of group and individual conversations, the article is written, mediated and edited by one staff member – Learning Producer Dr. Emeri Curd – whose role is to listen to conversations and draw out the key and significant themes. The excerpts are as close to uninterpreted as possible and allow for staff to speak in their own voice. These “little narratives” (Lyotard, 1984, p.22) – are woven together to allow for four voices to be in conversation with one another. Dr. Fiona Whelan, who’s work we cite commonly in this article, is one of the voices who we feel it would be remiss not to note here.

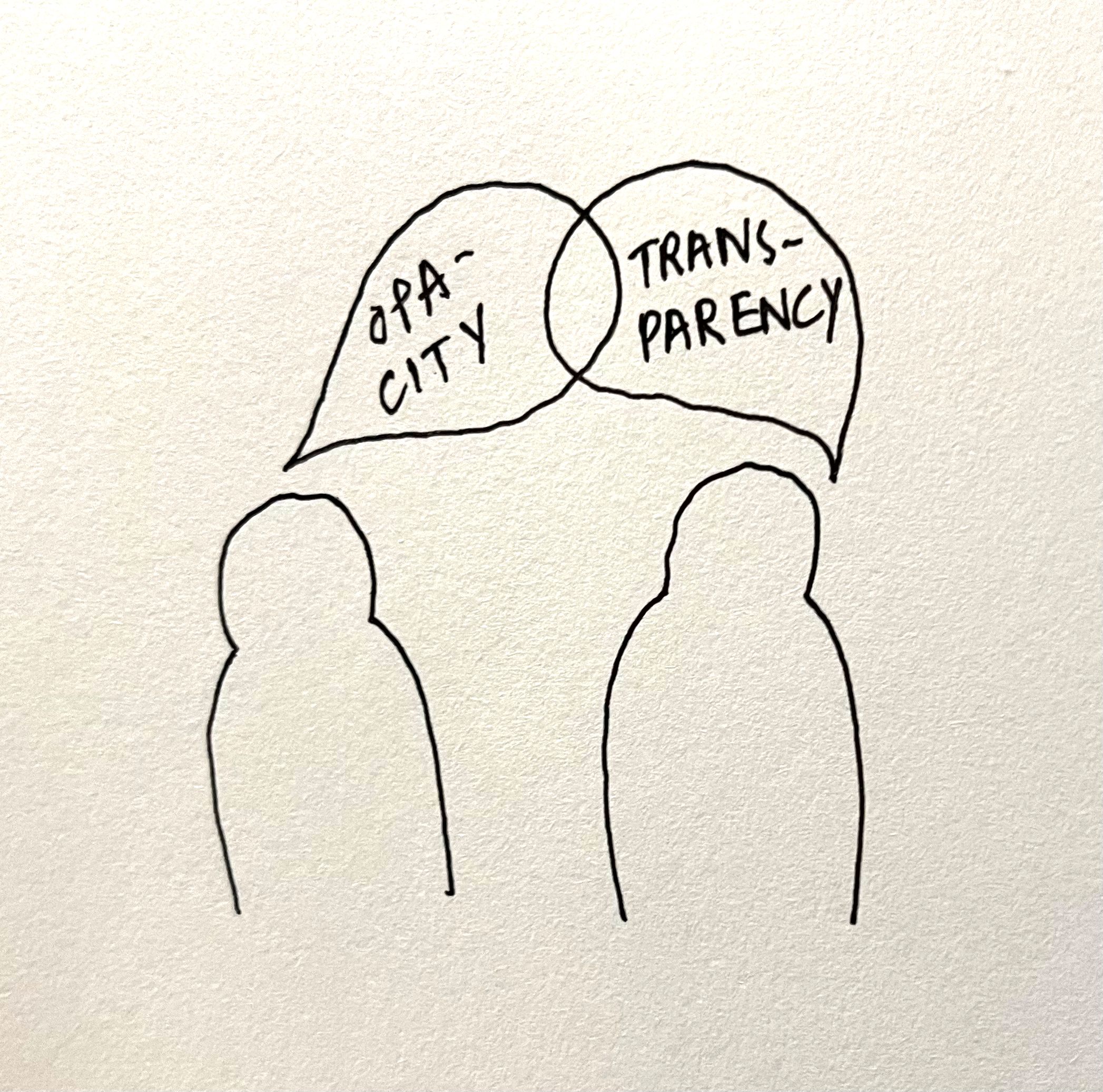

The first section of the paper is written/discussed with Patrick Fox and is a framing device to explore what being a learning organisation means in practice, provide context for our understandings of leaky and sticky knowledge, as well as how systems can be freed up to create critical and creative spaces. Patrick frames this practice as a collective endeavour led by producers and workers within the organisation. Senior Producer Emily Gee responds to Patrick’s reflections with a focus on the importance of metaphor in our work, and how that cultivates a different type of knowledge and value system outside institutionally valued knowledge. Lastly, Kate Houlton, Children and Young People’s (CYPs) Producer, further examines knowledge and power in the context of permaculture design patterns, asking how this destabilises and repositions the role of young people within current or traditional knowledge systems. To conclude, Emily reflects on the criticality of utilising opacity and transparency functions within the producer role, and how that might conflict with different approaches internally and externally.

Hidden Collaborations

Our methodology follows the idea that all writing and research emerges from “hidden collaborations” (Tsing, 2015, p.viii) which are mostly intangible in this article, but nevertheless present. Anna Tsing’s account of “hidden collaborations” scrutinises the inadequacy of transactional methods of citing and crediting collaborators. In practice, we (researchers, artists, producers and practitioners) understand that knowledge is born through complex, messy conversations, meetings, relationships and interactions. In the construction of knowledge, there are many more participants than can be named or traced back to the source, each with their distinct expertise and differing ways of ‘knowing’.

Theorist and poet Fred Moten touches on this idea in ‘The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study’ (Harney & Moten, 2013), when he reflects on how theories and ideas develop across and beyond nonlinear experiences of time. For example, he says:

It feels more like there are one or two things that I’ve been talking about with people forever. And the conversation develops over the course of time, and you think of new things and you say new things. But, the ideas that stuck in my head are usually things that somebody else have said (Moten, 2013, pp.103).

Frequently, these discursive micro-interactions are complex, not linear or fixed, allowing for “a multiplicity of competing discourses” (Rear, 2013, pp.6), meanings and knowledge, contributed by different individuals and groups “as a result of discursive, political processes” (pp.4). This premise underpins the ideology for this paper and our wider organisational understanding of knowledge creation. Mouffe and Laclau’s (1985) “field of discursivity” posits meaning and the creation of knowledge through discourse as a web and reinforces the idea that not only is knowledge constructed relationally, but also creates “surplus meaning” often in competition with different fields of practice and meaning-making; which could account for the complex histories and linguistic typologies of community and socially engaged art. In Mouffe and Laclau’s theory, “any discourse is constituted as an attempt to dominate the field of discursivity, to arrest the flow of differences, to construct a centre” (Mouffe & Laclau, 1985, pp.113). Differently at Heart of Glass, we resist the notion of acquiring or constructing a centre of practice due to the idea that “the centre cannot hold” (Fox & Tiller, 2023, pp.9). Instead, we choose to acknowledge that we are part of a collective experience, rather than a centre that builds frontiers or territories to and of knowledge. We have an obligation to share some of the knowledge we create together (with some concessions which we will explore later in the paper).

Through the learning programme at Heart of Glass, we are currently undertaking a slow, long-term reading group titled ‘Reading for the Restless’, led by artist Grace Collins. The informal reading group comprises a fluid cohort of fifteen to twenty participants, taking place both online and in person. ‘The Undercommons’ (Harney & Moten, 2013) was chosen as one of the four texts to read together and has been particularly compelling concerning current conversations relating to the theme of this special issue ‘Gentle Gestures’. Whilst many of our hidden collaborations are held with community collaborators and participants, there are also many more unspoken collaborators, including the authors of texts such as Harney and Moten (who have also made their work open source for those outside the academy to engage with). In this way, the discursive web widens to incorporate ideas from artists, community researchers and members, as well as publics; to academics, musicians, performers and poets; as well as borrowing ideas and concepts ‘illicitly’ from institutions. Whilst collaboration with some of these more powerful constituents is not stated or formally secured some kind of reciprocal hijack takes place. In the ‘Reading for the Restless’ reading groups, sometimes this feels like a kind of ‘piracy’ with an ambition to redistribute learning outside and beyond the blurred boundaries of an accredited institution. In ‘The Undercommons’, Harney describes this through the work of philosopher Félix Guattari as “idea thievery” (2013, pp.105). In this way, by holding reading groups to think through and with the ideas of others, we can act fugitively to “hack concept” and “squat terms”, “as a way to help us do something” (ibid) beyond the academy.

A conversation on learning with Patrick Fox

Emeri: What does being ‘a learning organisation’ mean for Heart of Glass?

Patrick: Our approach is to state genuinely that we are a learning organisation and our work takes the form of creative enquiry. Our commitment is to work within and understand the complex ecologies initiated and sustained by collaborative practices and spaces, or to ‘make the road by walking’. A stock phrase from the aforementioned early days was that we were ‘building the plane whilst flying it’. What this meant for us was that everything we set out to do required us to create the conditions to allow it to happen. We did not inherit any assets, procedures or unhelpful baggage – we were starting with a blank page albeit drawing upon histories of community organising and collaborative and social arts practices, and local knowledge. If we wanted to contract an artist, we wrote the contract together. If we wished to work in a public space, we introduced ourselves to often confused officials, sell them an idea and build trust with little frame of reference. It was exhausting and exhilarating and meant that our practice fused together in the process. As a result, we continue to be fit for purpose, designed in the image of what we are trying to achieve.

I’ve since learned that “building the plane whilst flying it” (Schenkels & Jacobs, 2018) is a recognised management style that favours agility over flexibility, and that it was not just a concept we invented to describe how we were feeling at that time. It has since become a conscious concept for us as a team – a reminder to challenge conventions or conditions as we find them or limit ourselves to inherited understandings of what may or may not be possible. To ask why, or more often why not – and try to build relationships that help us push through imagined barriers. Why can’t we turn a rugby stadium into an arena for live art? Why can’t we turn an empty shop unit into a multidisciplinary arts venue centring mental health? Why can’t we transform an office building into a drive-in cinema space? Why can’t we challenge some of the limiting conventions of arts participation and create authentic spaces of critical exchange and enquiry?

This process has become easier over time, aided by examples of work that provide conceptual evidence to sceptics (and sometimes funders), providing confidence to partners to step into the unknown with us. Those early days felt like a hijack, as we attempted to provide assurance to partners (who are usually more attuned to logic models and designed outputs) that we could and would unearth ‘the gold’. It was not an easy task. On reflection, I’m unsure how we managed to achieve it. Often, it was the passion of the team, artists and communities often got us over the line. Over the course of the last ten years we’ve seen the sector bend to our thinking and with that, a greater recognition of the value of process and intangibility of outcomes is starting to emerge. However, anyone engaged in this work knows that the battle is far from won.

Heart of Glass is now part of Arts Council England’s strategic National Portfolio (NPO) since 2018 and receives funding support from Paul Hamlyn Foundation and Esme Fairbairn Foundation to name a few. Whilst making the case for our approach has proved easier over the course of evolution, the work itself has become more complex in a rapidly changing world. If community arts practice is a shipping forecast that tunes into the conditions of our world, the forecast is an extremely challenging one, and one of conflict. Whilst there is a greater shared understanding of power, privilege, representation and systemic inequalities, these understandings also coincide with a more divisive, cruel and uncertain world. We feel the vulnerability of our partners, the precarity of our artists and the challenges faced by the communities we work with.

Emeri: In some areas of practice and research, “leaky” and “sticky” knowledge is theorised as a device for “espionage” (Ferdinand & Simm, 2006). I’m interested in this idea, and it makes me think of the radical potential for hijacking systems that were not made for ‘messy work’ – as community arts is commonly described. Do you think this bears any relation to our work as an organisation?

Patrick: Our current and future programme focuses on a theme of ‘Speculative Futures’, exploring movement rights, climate justice, queer rights, and disability justice and the notion of leadership from the margins. Our work attempts to create space for different forms of activism, knowledge and experience. We orient these programmes through our values – care, collaboration and challenge – and our commitment to being a learning organisation. To us this means never allowing the edges to form so fully that we become fixed – and being open to new knowledge, new experiences, and new ideas to propel us, or shift our course – whether this be a programme focus, or an updated policy. We are a mirror of the practice we support – we are not the expert although we have expertise that we can share, but we also require the ability to accept different forms of expertise and knowledge. We’re interested in what it is that we can only know together.

The permutations of the work are endless. It can be artform specific, such as visual arts, music or dance, or interdisciplinary involving collaboration across a range of artforms. It can also involve collaboration with non-art agencies, such as social inclusion organisations, local authorities, education providers, health authorities and community development groups. The artwork produced can take many forms and due to the collaborative nature of the work there is strong emphasis on the artistic process, so the creation of an ‘art object’ is not always appropriate, necessary or desirable. An event, a situation or a performance might feel more intuitive. Indeed, the process itself can be the artwork.

Any discussion of this practice inevitably raises questions around labour, knowledge exchange and power dynamics, as well as the need for an aesthetic language that describes the process and the experience, opposed to a final ‘single authored’ product or object. The work also requires discussion about what we mean by the social, as invariably this work is about groups of people coming together with different knowledge, views, lived or accrued experience and values coming together and re-imagining the world; whilst drawing upon the skills of the artist and their practice. The overlap of all these Venn diagrams is the sticky knowledge. The stuff we feel when we are in a shared space together.

A conversation on enquiry with Emily Gee

Emily: I’ll pick up from Patrick’s description of an organisation with porous edges, open to the constant possibility of learning, and note how this doesn’t mean that we are a shapeshifter (we’re grounded in a set of shared values and intentions) but that we must be in a position of ‘expecting’, that such learning necessarily demands attention and potentially a response, whether an addition or a movement, or something deeper and more fundamental.

Very often in this work I return to the beginning of a loop, a reminder of how if you don’t walk with it, humility will catch up with you sooner or later. A constant cycle of learning which builds and expands but also burrows out and empties, and in doing so somehow also demonstrates to me how little I know in the kinds of certainty that can be confidently shared in a paper, resolutely articulated through words on a page, instead existing as those things that I know here, now, and also those knowledges that I ‘only’ hold a piece of (Haraway, 1988).

In talking about this practice – a practice which is always multiple (Bergson, 1913; Deleuze & Parnet, 1987) – I recognise my inability to do so without my hands, without the language of poetics, analogy and metaphor. If I were forced to speak about this work without those, I couldn’t, but also, I wouldn’t: part of that inability is also a refusal. I know that, at its best, work in this realm holds a precious space of simultaneous possibility – beyond and that possibility unfolding in the now because it always was, infinitely nuanced and intricate and incredibly simple – a liberatory experience. Additionally, this practice can be ever-shaped into forms which replicate, reinforce, disguise or temporarily numb the impacts of living (or surviving) within the structures of the “imperialist white supremacist capitalist patriarchy” (hooks, 2014, p. 26) – as my intention is the former, I am an imperfect practitioner. I rely on the possibility of non/meaning that poetic language offers to articulating the experience of an embodied practice, and therefore the learning or sharing of knowledge which happens within it, without fixing in place. I also rely on this form of articulation to navigate between the ways this practice can operate, as outlined above.

Emeri: ‘Leaky’ knowledge is theorised as knowledge that escapes through ‘weakened’ boundaries within an organisation. I’d be interested to hear your thoughts on what happens when we co-opt this idea as a regenerative device, and if we purposefully run towards opening those spaces to let knowledge flow in?

Emily: In relation to ‘leaky knowledge’, firstly I am suspicious of what business terms might be sneaking into non-corporate spaces with each letter, but if I ignore this for a moment and focus on the notion of leaky, I can understand a flow between, out beyond the boundaries of one body (Gumbs, 2020), a ‘failure’ to contain. When we have spoken before about how projects unfold, many of the descriptions I use end up returning to metaphors of bodies of water, rivers in particular, and they’re particularly present at the moment through my collaboration with Youngsook Choi and Wen Di Sia, for whom rivers are an ongoing love (Choi & Sia, 2023). And so, to speak of the movement (as in a dance, not as a transference) of knowledge within a project (and beyond its own body) in these terms, we can understand it as a multi-layered series of constant, non-linear flows, cycling but not necessarily returning to the same point of beginning. The potential for leakiness to occur in such a scenario is great, inevitable even, and often desirable – in our version of leakiness, we do not necessarily experience a loss of control, or content, but instead a new, unexpected, path to flow through, unfamiliar banks to feel out.

At the beginning of a project (which always has beginnings long-before this one) we enter a space of both shared and individual enquiry, a series of open questions which are brought into being through meeting one another and finding the points at which our knowledge, experience and curiosity meet. Very basically, we work to explore our questions through playing, through experimenting, through reaching for the language, together, and along the process of a project our lines of enquiry may split, like distributaries, as we find a new route or hit a rock. Running alongside this project-specific exploration, are a series of parallel streams for anyone involved, for me this is an on-going enquiry around practice, and what and how this particular project encounter is revealing, troubling, or building complexity into my knowledge of this work.

Much of what we (within a project, or within the organisation) let free flow versus what we direct back into the rocks, or keep held within a well, is determined by intentions and what emerges in response to the questions we have been exploring, an unfolding negotiation with ourselves and each other. There are a series of questions that I have around knowledge that emerges, that is shared and that builds through projects, and the responses to which determine in many ways the shapes of the channels of such flows. Many of these are around questioning who the knowledge is for, is this exclusively for those people whose bodies were a part of fostering it, or have we decided that there are elements of it which we have a desire or a responsibility to share, if so, who with, how?

A conversation on power with Kate Houlton

Emeri: When we last spoke, you mentioned a web or net when visualising projects associated with children and young people’s programme and knowledge systems. This aligns with our work with permaculture principles and embedding these within our research principles. Could you tell me a little more about this and how the messiness of webs/nets can disrupt traditional knowledge and power imbalances within our work with CYPs?

Kate: When Emily talks about people coming together from different experiences, with different knowledge, and how this might create different systems of knowledge, I am reminded of webs and nets. In permaculture design – an approach we are currently embedding within our organisational practice – a web typically serves to connect resources. In nature, webs balance the distribution of energy of inputs, flow and outputs. And I thought that this was an interesting way to think about our practice at Heart of Glass in a lateral way. In permaculture design, the web is perceived as a non-hierarchical structure to share resources, such as knowledge. The web represents some of the dynamics of power within our projects and how we try to create a more equal distribution of power and resources with the people we work with. Initially I began thinking about this as a web. However, as I reflected, I started to think about the differences between webs and nets. A web obviously has that central ‘starting’ point. This kind of approach with a central point (such as the organisation) or person (such as a producer) is one we are actively trying to challenge.

Emeri: It’s interesting because when I think about the work as a net or as web, I don’t often think about the maker of them. I think about the connections between the strands and the intersection and collision of their threads. So, it’s interesting to place spiders back into their webs. It also reminds me that at certain times of year walking down by the river where I live there are reeds that grow from the banks of the river. On certain days when it’s particularly frosty and the light is shining in a particular way, there are just hundreds of illuminated cobwebs. And this is all you see, and you don’t necessarily see the spiders or the makers who’ve like been working all night on these beautiful things. But there’s the sheer mass of them. For Heart of Glass, if each one of those webs represents a project of which there are many, it emphasises the complexity of the work.

Kate: That’s also interesting if you reflect on the visibility of those webs. In so many cases you never see the totality of them. So, as you say, on rare occasions you can glimpse the complexity of them. And this goes back to Emily’s reflections on visibility and sharing: What knowledges might emerge through the process, when do they emerge, who are they for and who decides if/how they are shared and to whom? As a viewer, you don’t see the energies of the weavers and how and what work makes up a project, you only see the result and that can be quite spectacular, but the work is in the collective.

I think differently, maybe a net represents our aspiration to decentralise away from a central weaver or person or producer, a central structure, a central focus, and letting things slip out of that typical dynamic of power and distribution. To go into more detail, I was thinking about the individual threads of a net weaving together to form a complex, enmeshed net. The individual threads of the net might represent individual people or collaborators. Alternatively, they could also represent resources, individual experiences, knowledge, thoughts and enquiries, and conditions; and the moment or point they meet or connect is where new knowledge is formed and fused, ripe with possibilities for collective knowledge. Zooming out of this idea of an individual project as a net, I am also led to think about different sized projects as nets and the spaces between the nets held by the organisation. What information is held in these gaps between the nets? Do the gaps represent leakage within these spaces, and how does the leakage feed into a wider understanding and learning across the organisation? Are these leaky spaces advantageous to our way of working or do they pose problems? Often, we see these spaces open to possibility and the unknown. Again, this reiterates the possibility of thinking about our practice as a net, rather than a web. It’s not the responsibility of one singular individual to maintain – within the context of a web, the spider is the weaver of the web – whereas a net has multiple makers, endings, beginnings, and boundaries. And maybe there is a starting point, but, once it’s created, it’s hard to identify the starting point and the end point. It’s much more about the process of weaving and stitching, making, and remaking. And everything in between that we embody collectively, rather than focusing on an end point or goal.

In this in-between space, knowledges are woven together, and that binding represents collective strength, created by individual threads. Once created, it holds something in the safety of the environment it was made, rather than being taken out of context to be disseminated elsewhere. Again, I don’t think this way of working necessarily relates to young people only, but I think there is a redistribution of hierarchy and power which is key to repositioning young people and their role in these dynamics. Who in these spaces are we listening to and who are we learning from? Our current collaboration with Dr Fiona Whelan is one of those examples that highlights our organisational learning to listen to and hear the people we work with more fully. In recent times, through our invitation to the role of ‘Listener-in-Residence’ for ‘With For About: Care and the Commons’ Fiona’s approaches to listening have also extended to centre dismissed or sometimes inaudible voices – such as our more-than-human neighbours’ (Whelan, 2023, p.3).

Emeri: Yes, you’re right. Again, some of the things that we’re talking about really go back to permaculture ethics and design principles, and the relationship to these natural patterns is in keeping with our attempt to divert away from exploitative relationships between people and land; and how this approach is also mirrored in trying to move away from similar systems of evaluation and research. The power dynamics here are key – those who are evaluated, and those doing the evaluation. I think the discomfort with some of these power relations has been underlying at Heart of Glass for some time, but we are now able to articulate them in terms that feel helpful.

Kate: Yes, it always goes back to language, doesn’t it? And that knowledge, like language, finds a way to describe itself and that helps us to articulate what we are doing or exploring through our work. And this may require new languages or a new way of articulating the shared experiences that emerge through different projects. For me, taking part in ‘An Introduction to Permaculture for Artists and Creatives’ course led by artist and permaculture design facilitator, Liz Postlethwaite, was a lightbulb moment. I felt I had found a language to articulate the work we do at Heart of Glass.

Emeri: Yes, so language is always in transition too. I think that’s what I was trying to identify when I was talking about the term shapeshifting because I think in some ways that term could be perceived as an organisation acting inauthentically. But when I think about shapeshifting, what I mean to say is that by undertaking amorphous practices we have the radical and emancipatory capacity to transverse beyond the limitations of a particular or singular field (Raunig, 2006). Without a set building, venue, field or discipline, we can multiply, regenerate, transverse and transform laterally; much as natural elements might (such as mycelium), and this is how I think about shapeshifting as a multi-species approach to art-making and organising. Maybe this is too ambitious or requires more theorising, but it feels like an approach centred in permaculture design too.

Kate: Yes, so what you call shapeshifting is also about being open and responsive to a process that is always unfolding. The way I would interpret shapeshifting is to be flexible to the possibilities and the ability to flex, flow, shift and change in response to the conditions that we are in or the conversations we’re having, whilst also grounded in a set of shared values and intentions as Emily mentions above. I think that also reflects a theme of our work as bodies of water, as Emily suggests. When I think about rivers like Emily mentions, and the flow of knowledges and what emerges through our work, I am reminded of the famous quote by Bruce Lee (1971):

Be like water making its way through cracks. Do not be assertive, but adjust to the object, and you shall find a way around or through it. If nothing within you stays rigid, outward things will disclose themselves.

Empty your mind, be formless. Shapeless, like water. If you put water into a cup, it becomes the cup. You put water into a bottle, and it becomes the bottle. You put it in a teapot, it becomes the teapot. Now, water can flow, or it can crash. Be water, my friend.

Conclusion

Whilst we continue to remain in a space of enquiry around how our MEL practices will develop in the future, and we continue to safeguard space for these ideas to move and transform, we are also thinking about the expectation to share the knowledge created within these spaces more widely. This expectation comes both internally and externally; from learning and communication workers; as well as externally, from across sectors, with students, researchers, and artists, or those who may benefit from the work such as cultural and arts workers and community workers. For Emily, this leads to another set of questions around:

Whose expectations are we sharing into, and whether such knowledge will be received without demands to reveal (whether our processes, our identities, our experiences) in order to justify what we assert, where do we have a right to opacity (Glissant, 1997, p.190)? And finally (for here, now) a questioning around the presumption that knowledge, learning, is necessarily always positive, that the accumulation is pain-free, that the knowledge we arrive at is something that is easy to hold, what do we do with this knowledge?

What we do assert in the work, as is tangible in this article, is that across our team, there is difference – or agonism (struggle between adversaries) – in the way that we conceive our work; with each of us holding reflective practices in our hands in different ways, some with looser or tighter grips, each informed by different experiences. For Mouffe, what is important here is that this ‘conflict’, does not take the form of antagonism but is reflected in the acknowledgement and the welcoming of plural passions, views and voices, to challenge both the order of society, the sector, as well as status quo within our communities within their webs and nets (Mouffe, 200, p.16).

Lastly, in writing this article, we have begun to expand our praxis and research aims as a collective of art workers and producers. This we hope adds to a growing multiplicity of “little narratives” (Lyotard, 1984, p.22) that splinter “widely accepted truths” about people, cultures and institutions, as well as their value and the knowledge they produce. This we feel is especially necessary at a time when community arts practices have become increasingly popularised and decontextualized away from the practice and histories of its origin. In part, we hope this helps us build a many-voiced, multi-faceted and multi-perspective piece of work, reflected in the audible and inaudible voices engaged in the work. Through this methodology we are continuing to consider how we might flood our pre-existing channels, share power and co-create our research aims in practice; where everyone we work with is a researcher in name as well as in practice.

About the contributors

Dr Emeri Curd (they/them) is Learning Producer at Heart of Glass supporting the development of learning programmes and resources for artists, producers, and cultural, community and education practitioners. Emeri has worked as an artist-facilitator and action researcher over the last ten years in museums, galleries, higher education and community settings to facilitate research with young people, LGBTQIA+ groups, socially engaged practitioners and art workers. Emeri works with these groups as co-researchers with the aim to shift power dynamics within and outside institutions and academic spaces.

Patrick Fox (he/him) is Chief Executive and founder of Heart of Glass. He is a producer, commissioner and senior arts leader who supports artists to engage with communities of place/ interest to create contemporary work that reflects the politics of our times. He is former director of Create, Ireland’s national development agency for Collaborative Arts and the former Head of Collaborations and Engagement at FACT Liverpool, leading the acclaimed arts and older people project tenantspin as part of his portfolio.

Emily Gee (she/they) is Senior Producer at Heart of Glass, supporting the organisation’s programme of commissions and residencies and has worked within collaborative and community practices for over fifteen years, across many contexts.

Kate Houlton (she/her) is the Children and Young People’s Producer at Heart of Glass, supporting the creation of dynamic and ambitious enquiry led collaborations between artists, children, young people and their allies. Kate has worked as a creative producer and project manager in the arts and cultural sector for over fifteen years with organisations including Manchester International Festival, In-Situ and Ultimate Holding Company.

References

Ashley, S., (2005) First Nations on View: Canadian museums and hybrid representations of culture. eTopia, pp.31-40.

Bergson, H., (1910). Time and Free Will: An Essay on the Immediate Data of Consciousness. London: George Allen & Unwin LTD.

Choi, Y., & Sia, W., (2023). ‘In Every Bite of the Emperor – Malaysia’. Heart of Glass. [online] Available at: https://www.heartofglass.org.uk/cms/documents/In-Every-Bite-of-the-Emperor-Malaysia.pdf. [Accessed: 20/02/24]

Deleuze, G. and Parnet, C., (2007). dialogues II. Columbia University Press

Fox, P. and Tiller, C., (2023). ‘Building Blocks’. Heart of Glass. [online] Available at: https://www.heartofglass.org.uk/cms/documents/HOG-BuildingBlocks-2023-2025-1.pdf [Accessed: 30/08/24]

Foucault, M., (1980). Power/Knowledge: Selected Interviews and Other Writings 1972-1977. New York: Pantheon Books.

Ferdinand, J., & Simm, D. (2006). ‘A different look at sticky and leaky knowledge: Economic and industrial espionage.’ In the International Conference on Organizational Learning, Knowledge and Capabilities (pp. 1-25).

Giroux, H.A., Lankshear, C., McLaren, P., & Peters, M. (1996). Counternarratives: Cultural Studies and Critical Pedagogies in Postmodern Spaces (1st ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203699102

Glissant, É., (1997). Poetics of relation. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press.

Graziano, V., Mars, M., & Medak, T., (2019-current). Pirate Care. [online] Available at: https://pirate.care/. [Accessed 02/09/24].

Gumbs, A. P., (2020). Undrowned: Black Feminist Lessons from Marine Mammals. United Kingdom: AK Press.

Jeffers, A,. & Moriarty, G., (2017). Culture, Democracy and the Right to Make Art: The British Community Arts Movement. United Kingdom: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Haraway, D. (1988)., ‘Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective’. Feminist Studies, 14 (3), pp.575-599.

Hardt, M., (2000) Empire. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

Harney, S., Moten, F. (2013). The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning & Black Study. United Kingdom: Minor Compositions.

hooks, b., (2014). Teaching To Transgress. United Kingdom: Taylor & Francis.

Horton, M. & Friere, P., (1990). We make the road by walking: Conversations on education and social change. Temple University Press

Kelly, O., (1984). Community, art and the state. London: Comedia

Lee, B., (1971). “The Lost Interview”. Interview with Pierre Berton. 9th December (1971, Hong Kong.

Lyotard, J.-F., (1984). The postmodern condition: A report on knowledge. University of Minnesota Press.

Lukács, G., (1923) History and Class Consciousness: Studies in Marxist Dialectics. Massachusetts: MIT Press.

Mollison, B. and Holmgren, D., 1978. Perma-culture one. A perennial agriculture for human settlements. United Kingdom, Tagari Publications.

Laclau, E. and Mouffe, C., (1985). Hegemony and socialist strategy: towards a radical democratic politics. London: Verso.

O’Donnell, P., Lloyd, J., & Dreher, T., (2009). ‘Listening, pathbuilding and continuations: A research agenda for the analysis of listening’, in Continuum: Journal of Media and Cultural Studies, 23:4, p.423–39, original emphasis, cited in Grossman & O’Brien, ‘Voice, listening and social justice: a multimediated engagement with new communities and publics in Ireland’, in Crossings: Journal of Migration and Culture, 2 (2011).

Raunig, G., (2006). ‘Instituent Practices: Fleeing, Transforming, Instituting’. Transversal texts. [online] Available at: https://transversal.at/transversal/0106/raunig/en. [Accessed: 20/02/24].

Rear, D., (2013). Laclau and Mouffe’s discourse theory and Fairclough’s critical discourse analysis: An introduction and comparison. pp.1-26.

Rothe, K., (2014). “Permaculture Design: on the practice of radical imagination”. Communication+ 1, 3(1), 1-18. Doi: https://doi.org/10.7275/R58913S2.

Roy, A., Froggett, L., Manley, J., & Wainwright, J., (2018).’ Developing Collaborative & Social Arts Practice: The Heart of Glass Partnership 2014-2017: A Study by the Psychosocial Research Unit’. Lancashire: UCLAN.

Schenkels, A., & Jacobs, G., (2018). ‘Designing the plane while flying it’: concept co-construction in a collaborative action research project. Educational Action Research, 26(5), 697-715.

Tsing, A,. (2015). The Mushroom at the End of the World: On the Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruin. Princeton and Oxford: Princeton University Press.

Wakefield, S. and Koerppen, D., (2017). ‘Applying feminist principles to program monitoring, evaluation, accountability and learning’. Oxfam Discussion Paper. [online] Available at: https://oxfamilibrary.openrepository.com/bitstream/handle/10546/620318/dp-feminist-principles-meal-260717-en.pdf [Accessed: 20/02/24].

Whelan, F., (2023). ‘Listening, Interpretation, Colonisation and Decentering – Reflections on With For About 2023: Care and the Commons’. Heart of Glass. [online] Available at: https://www.heartofglass.org.uk/cms/documents/Fiona-Whelan-final.pdf. [Accessed: 20/02/24].

Williams, R., 1961. The Long Revolution. London: Pelican.